When I was a kid, one way to respond to an insult was to say “I’m rubber and you’re glue; whatever you say bounces off me and sticks to you.” Immediately, the sparring would change character and the resulting dialogue would all be about the new debating rule. The conversation would go something like this:

“You’re a dumb ass.”

“You’re fat.”

“I’m rubber and you’re glue; whatever you say bounces off me and sticks to you.”

“Ok, you’re the smartest person in the world.”

“Ha, you said I was smart!”

“No, that was supposed to bounce off you and stick to me. So I am smart.”

“No you’re not, you’re dumb.”

“No, now I’m rubber and you’re glue; whatever you say bounces off me and sticks to you.”

And so on. . .

Sometimes when I am reading arguments made by Trump supporters I feel we’re in third grade again. You simply cannot ever get through to them because they seem only to want to play the “I’m rubber and you’re glue” game, or the variation made famous by Pee-Wee Hermann, “I know you are but what am I?“. Whatever critique anyone might level at them gets turned around and thrown back, no matter how inapt. This sort of argument-by-inversion is an effective tactic of deflection, as in Trump’s famous retort to Hillary Clinton in the third Presidential debate: “No puppet, no puppet, you’re the puppet. No, you’re the puppet.” Sometimes it is even used preemptively, where the argument that should be used against them is instead leveled first at their opponents under the theory, I suppose, that the best defense is a good offense.

I had this feeling while reading the recent article “In the Russia Probe, It’s ‘Qui S’excuse S’accuse,” by Andrew McCarthy in the National Review. The title of the article, by the way, which the author uses without any apparent sense of irony, means “He who excuses himself accuses himself.” Given the title, you might be forgiven for thinking the focus would be on the Excuser-in-Chief, Mr. “No Collusion” Himself, Donald Trump. But no, you’d be wrong. It’s all about the FISA warrants against Trump’s campaign foreign policy advisor Carter Page.

The gravamen of McCarthy’s article, what the author calls his “essential point,” concerns “The use of counterintelligence authorities to conduct a criminal investigation of Donald Trump in the absence of a predicate crime.” McCarthy’s argument is that the FISA warrant against Page was simply a fishing expedition without any basis for believing a crime had been committed.

That’s a really good argument, and one I am very familiar with, but in a very different context (as I will explain below). But it is woefully inapt to challenge the FISA warrant against Carter Page. In fact, simply making this argument for Carter Page is itself really a case of trying to invert the argument as a tactic to take it away from those who might use it against the President.

Dispatching McCarthy’s argument about Page isn’t too difficult. The FISA application was made in October 2016, after the July 2016 release by Wikileaks of documents stolen by Russian agents from the Democratic National Committee, and the October 7 release of e-mails from Hillary Clinton’ s campaign manager John Podesta. The US Intelligence Community issued a statement on October 7, 2016, prior to the warrant application, stating that “the USIC is confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from U.S. persons and institutions, including from U.S. political organization.” In July 2018, twelve Russian agents were indicted for the hacking of the DNC e-mails.

So much for McCarthy’s “essential point” that there was no “predicate crime.” There clearly was. And the FBI had every reason to investigate Carter Page, a former Trump foreign policy advisor who had previously advised the Kremlin, had traveled to Russia in July 2016 and had reportedly been approached by Russian agents. The investigation was especially justified after learning via George Papadopoulos that Russian agents had approached the Trump campaign earlier that year. Let’s not forget that Donald Trump himself had called publicly for Russia to release Clinton e-mails on July 27, 2016. The facts in the FISA warrant amply provide probable cause to believe that the investigation of Carter Page would lead to the discovery of information relevant to the investigation of the crime that had been committed against the DNC. And we will find out eventually, I suppose, if the investigation also provided evidence of crimes committed by the Trump campaign, who by all appearances were eager to conspire with the criminals who illegally hacked the DNC.

But let’s go back to McCarthy’s core argument, which I think is correct. The FBI should not be using pretextual warrants to investigate presidential candidates where there is no indication whatsoever of any criminal activity. If not Donald Trump, is there maybe some other presidential candidate to whom that happened? Hint: her initials are HRC.

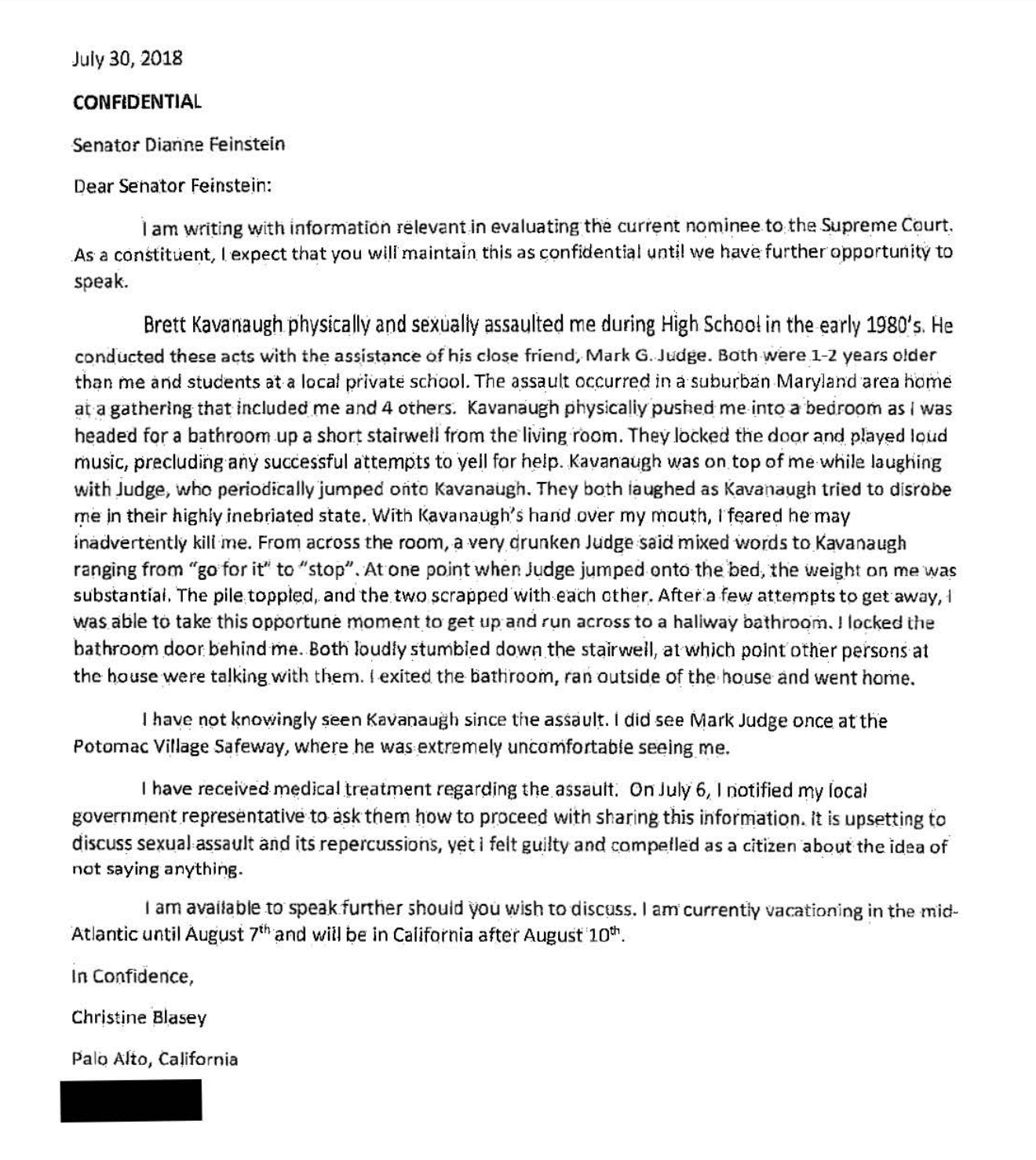

Last week I filed an opposition brief to the FBI’s summary judgment motion in the case I have brought to remove redactions from the search warrant obtained by the FBI on October 30, 2016 seeking evidence against Hillary Clinton. One of the only remaining redactions, most of which were removed only after I filed suit, is the name of the FBI Supervisory Special Agent who signed the affidavit in support of the warrant. The legal issue is whether that agent’s right to privacy is outweighed by the public’s right to know his name, and that issue depends on whether there is any evidence of wrongdoing by the agent. I believe I have made a good case for finding that the FBI did to Clinton exactly what McCarthy pretends the FBI did to Trump, namely, obtain a search warrant without any suggestion of a predicate crime. You can read my full argument below.

Today, President Trump ordered the release of redacted portions of the FISA warrant application against Carter Page, as well as other internal documents and messages by FBI officials. No doubt the documents will simply confirm the appropriateness of the FBI’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election, as was the case when Trump and his allies released earlier materials. And no doubt, Trump supporters will continue to claim, notwithstanding all of the evidence, that the disclosures hurt the FBI and discredit the investigation. Because, well, they are rubber and the FBI is glue.

I’ll have to wait for the judge in our case to decide whether the same level of disclosure will be applied to the search warrant against Hillary Clinton.

I. INTRODUCTION

This action concerns perhaps the most significant search warrant in the history of the United States, one which did not result in the discovery of any evidence of criminality, but nevertheless changed the outcome of a presidential election. The events surrounding the search warrant have received massive public attention, including countless articles, books, congressional hearings and even a DOJ Inspector General report. Yet much still remains unknown. Plaintiff has pursued the unredacted release of the search warrant and accompanying affidavit for nearly two years, and has been opposed by the FBI at every stage. This particular action already has resulted in the voluntary, if belated, release by the FBI of most of the information that had previously been withheld improperly. Only a few items – two agent names and an e-mail address — remain redacted, and those should also be released to the public.[1]

II. BACKGROUND

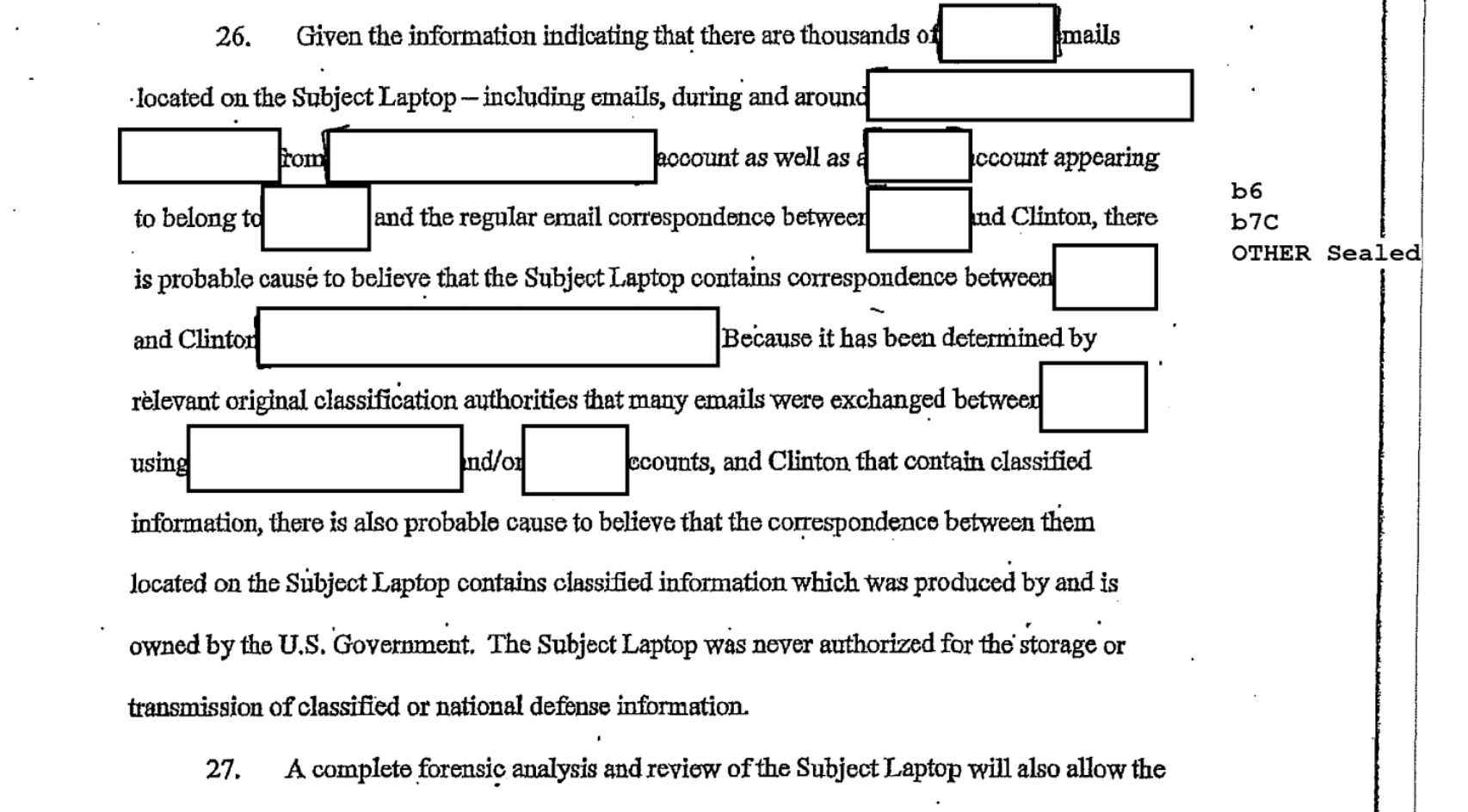

The FBI has withheld the names of the two agents who were responsible for the warrant application and execution: a Supervisory Special Agent (“SSA”) who signed the warrant application and affidavit, and a Special Agent (“SA”) who was present at the inventory upon execution of the warrant. Admittedly, the SSA appears to be the more significant of the two. Many, including plaintiff, have questioned why the SSA believed there was probable cause to search the Weiner laptop for emails between Secretary Clinton and her aide Huma Abedin. The affidavit itself provides very little in the way of probable cause:

- Given the information indicating that there are thousands of Abedin’s emails located on the Subject Laptop — including emails, during and around Abedin’s tenure at the State Department, from Abedin’s @clintonemail.com account as well as a Yahoo! Account appearing to belong to Abedin — and the regular email correspondence between Abedin and Clinton, there is probable cause to believe that the Subject Laptop contains correspondence between Abedin and Clinton during their time at the State Department. Because it has been determined by relevant original classification authorities that many emails were exchanged between Abedin, using her @clintonemail.com and/or Yahoo! Accounts, and Clinton that contain classified information, there is also probable cause to believe that the correspondence between them located on the Subject Laptop contains classified information which was produced by and is owned by the U.S. Government. The Subject Laptop was never authorized for the storage or transmission of classified or national defense information.

- A complete forensic analysis and review of the Subject Laptop will also allow the FBI to determine if there is any evidence of computer intrusions into the Subject Laptop, and to determine if classified information was accessed by unauthorized users or transferred to any other unauthorized systems.

(Declaration of David M. Hardy submitted in support of Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment (“Hardy Decl.”), Ex. K, pp. 90-91.)

Notably absent from that brief statement of probable cause is any indication whatsoever that the search would result in evidence of any criminal activity by Secretary Clinton. Rather, the entire probable cause statement seems directed toward a clean-up operation of what the FBI typically refers to as a “spill” of classified information. This is noteworthy because the entire FBI investigative team had already concluded, and FBI Director James Comey had already announced publicly, that (a) the mere presence of e-mails containing classified information could not support a criminal prosecution, and (b) the FBI was not going to conduct a spill clean-up operation.[2]

If not to clean up a spill (which of course required absolutely no urgency since the laptop was already in custody), why in fact did the FBI seek the search warrant on the eve of a national election? As set forth in the IG Report, Director Comey was very clear on this issue – he believed that the laptop might contain emails from early in Secretary Clinton’s tenure that had not yet been located, and which might lead to a criminal prosecution. (Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, footnote 4)

Comey told us that the potentially great evidentiary significance of the newly discovered emails would have made it particularly misleading to stay silent. But we found that the FBI’s basis for believing, as of October 28, that the contents of the Weiner laptop would be significant to the Clinton email investigation was overestimated. Comey and others stated that they believed the Weiner laptop might contain the “missing three months” of Clinton’s e-mails from the beginning of her tenure when she used a BlackBerry domain, and that these “golden emails” would be particularly probative of intent, because they were close in time to when she set up her server.[3] However, at the time of the October 28 letter, the FBI had limited information about the Blackberry data that was on the laptop. The case agent assigned to the Weiner investigation stated only that he saw at least one BlackBerry PIN message between Clinton and Abedin. As of October 28, no one with any knowledge of the Midyear investigation had viewed a single email message, and the Midyear team was uncertain they would even be able to establish sufficient probable cause to obtain a search warrant. (Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, footnote 4). [4]

Nowhere in the search warrant application executed by the SSA is the true design of the warrant – the missing three months of e-mails from early in Clinton’s tenure – disclosed[5], and for good reason, because there was no probable cause to support the belief that those e-mails would be on the laptop. The only fair conclusion is that the search warrant application itself was purposely misleading and pretextual. The SSA sought the warrant under false pretenses and failed to disclose the true purpose of the investigation.

What do we already know about the SSA and his role? According to the IG Report, the SSA assigned to the so-called Midyear team investigating Secretary Clinton’s e-mails worked immediately under Agent Lead Peter Sztrok. (Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, IG Report, FBI Chain of Command for the Midyear Investigation, page 45.) The SSA was part of the “leadership of the team.” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 315, n. 176.) The IG Report says that several witnesses described the SSA as “experienced and aggressive.” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 42.) [6]

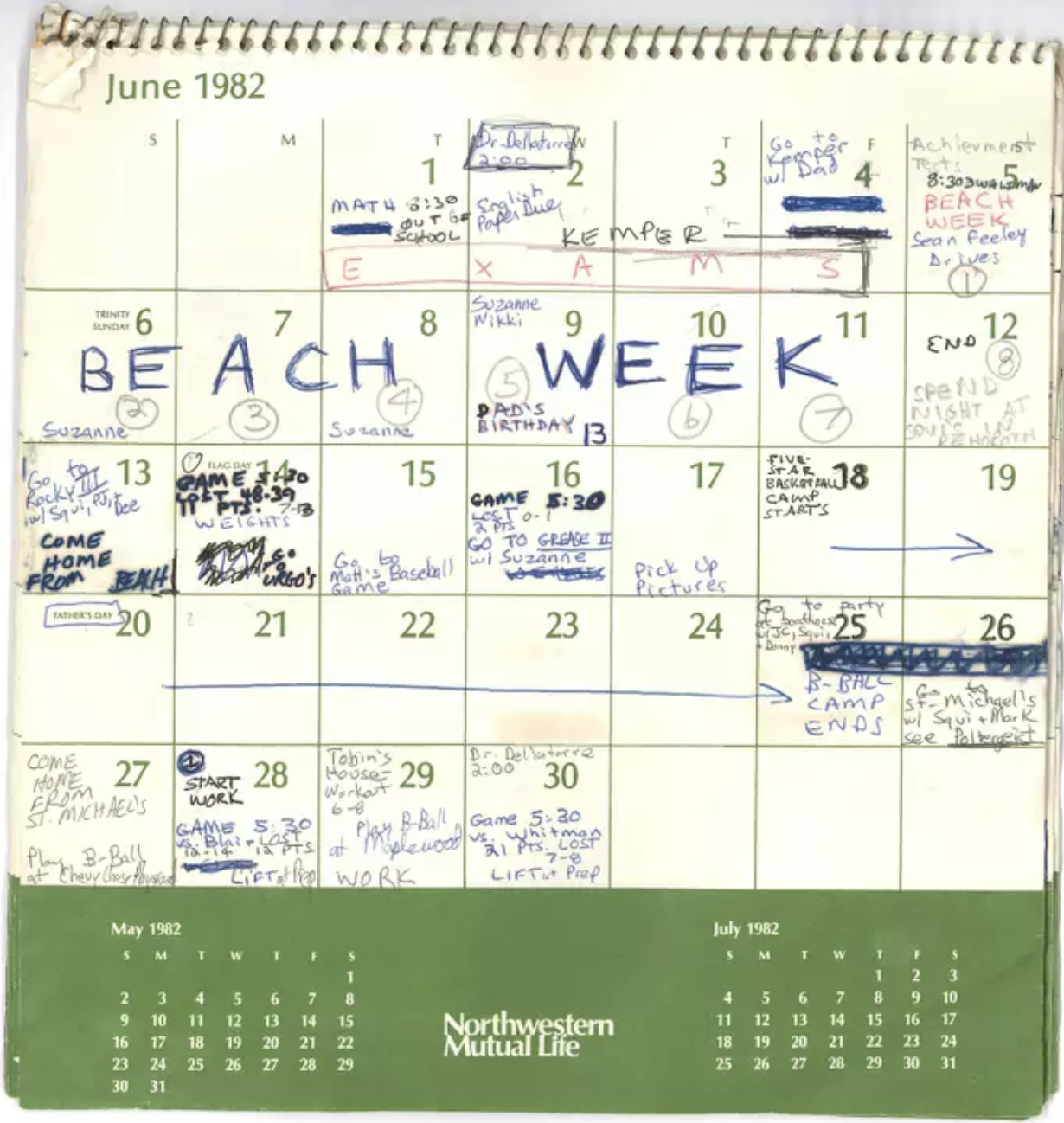

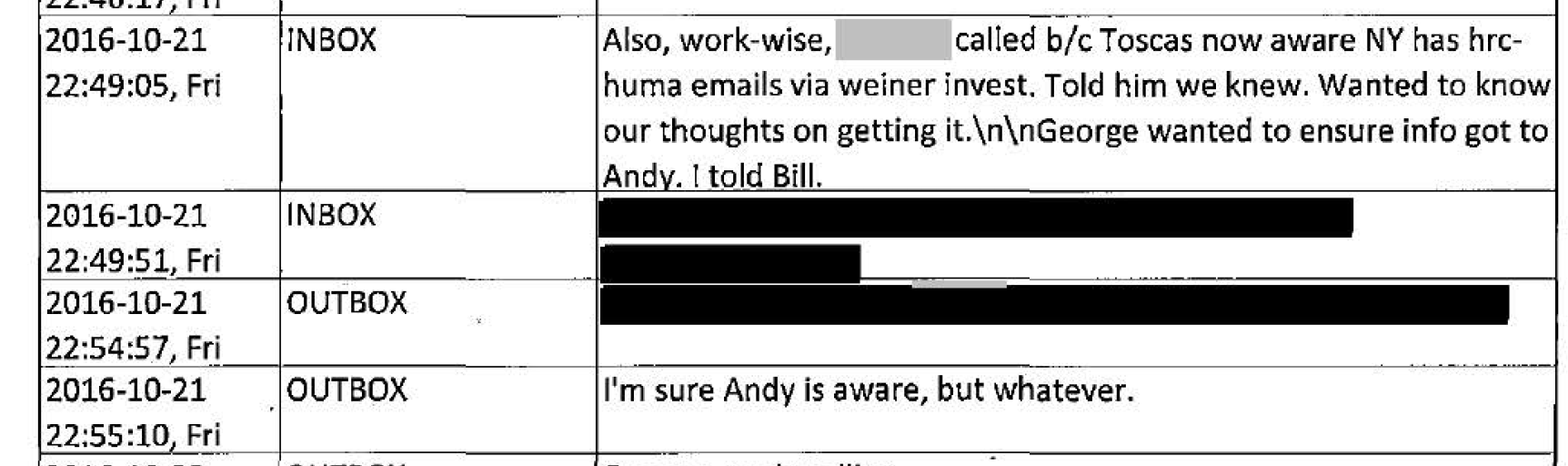

On September 29, 2016, the SSA was the first from the Midyear team to follow-up and speak with agents in the New York Office supervising the Anthony Weiner investigation regarding the discovery of e-mails between Clinton and her aide Huma Abedin on Weiner’s laptop. (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 285 et seq.) He told the IG, “Well, from my standpoint, I said we were going to, we were going to address whether we had enough for a warrant.” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 286.) He further stated, “I remember walking away the first time thinking that … we probably had enough [probable cause to get a search warrant to review the emails]. But I understood why that discussion wanted to be made, is that, you know, well let’s see what happens. . . . [T]hat lag in time was a result of allowing [the Wiener] investigation to proceed. And then they contacted us when they felt that they had a lot more information that needed to be addressed by, by or team. And then we proceeded with moving forward.” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 300.)

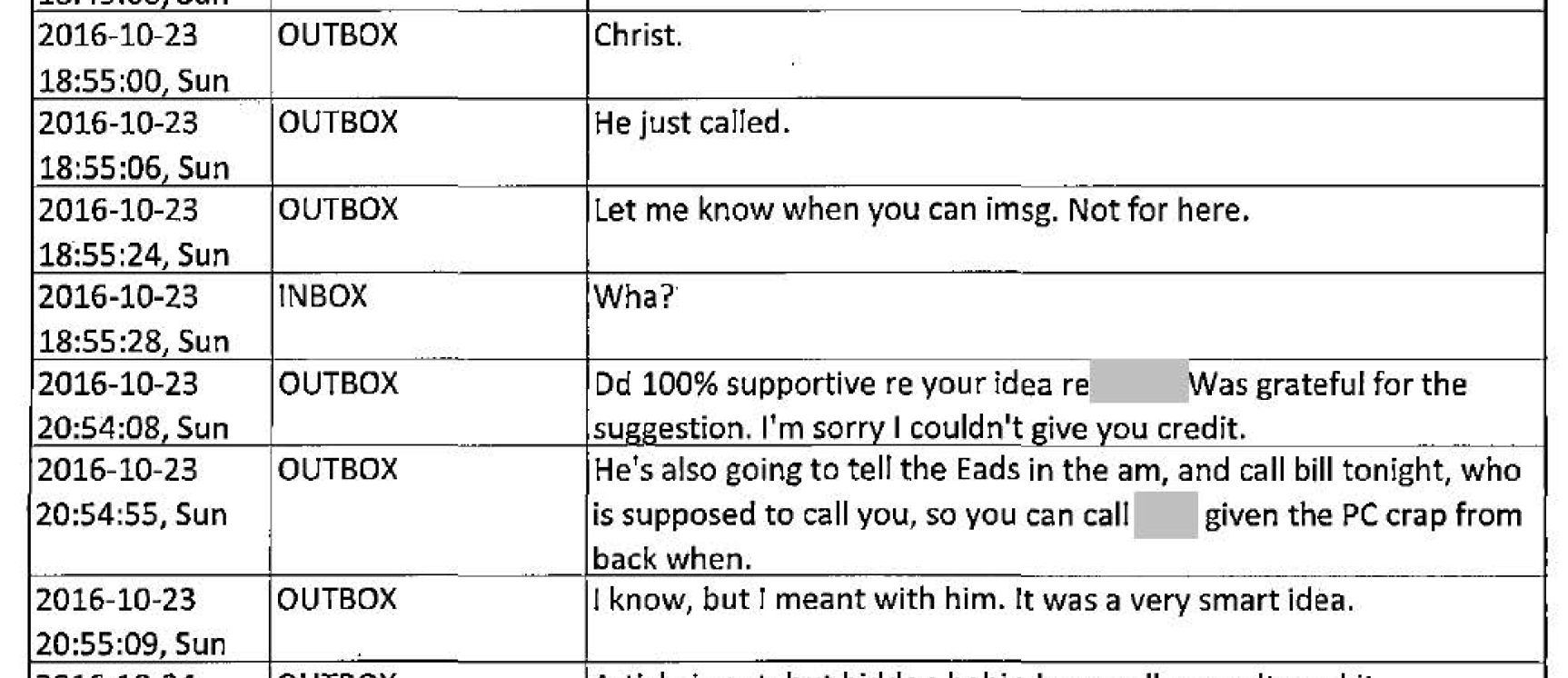

After Comey’s October 27, 2016 decision to reopen the investigation and seek a search warrant, Strzok informed the SSA and case agents to seek their input. (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 350 “What do you think about that? Are you, are you good? Are you, objections, are we horribly off-base? Are we not thinking of something?”). The SSA and the two case agents “ultimately agreed with the decisions to seek the search warrant and send the letter,” although one of the agents sent a text message saying “Due diligence—my best guess—probably uniques, maybe classified uniques, with none being any different tha[n] what we’ve already seen.” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 351.) The agent later clarified to the IG that he “did not expect to find emails substantively different than what the Midyear team had previously reviewed.” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 352.)

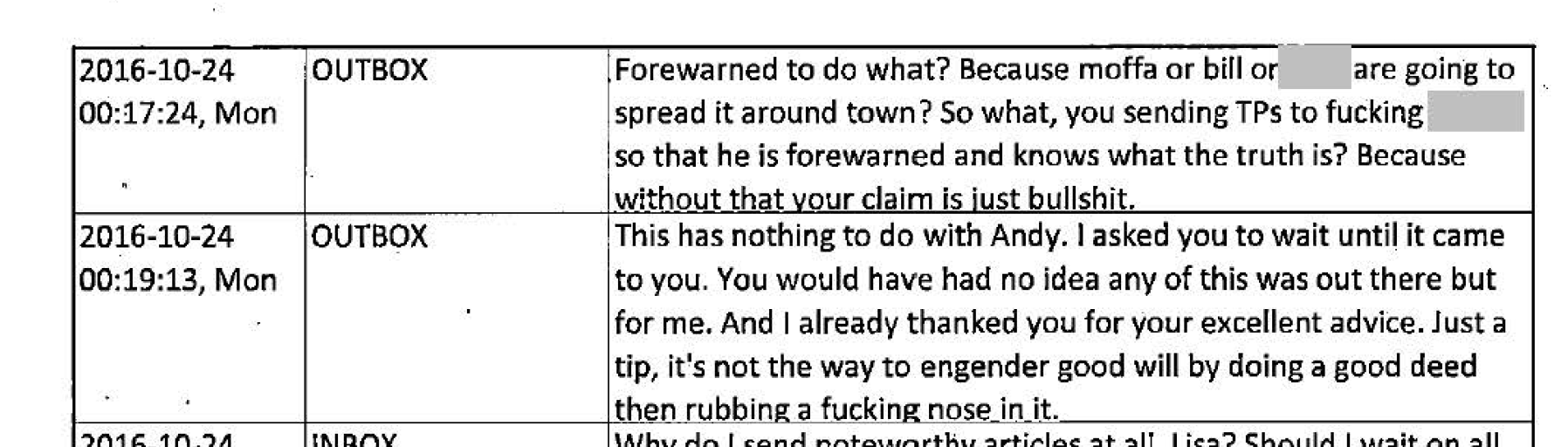

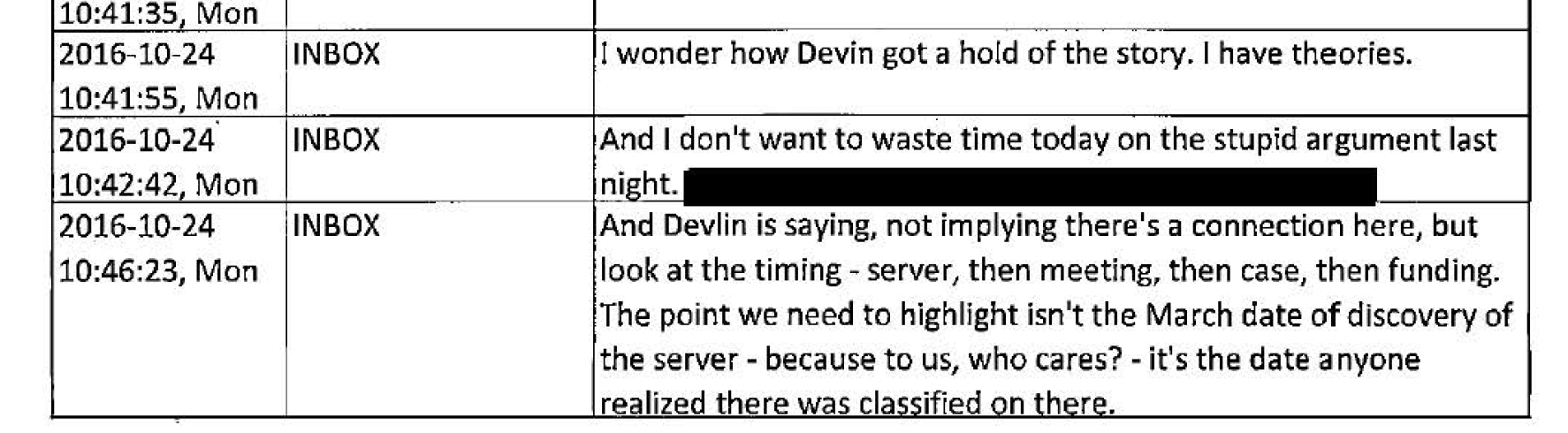

The SSA was involved in “a variety of robust discussions” with lead DOJ personnel about the reasons for the laptop search, which centered on the FBI’s interest in the “gap period (1st 3 months).” (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 352.) The DOJ prosecutors questioned the need for the search and disagreed with Comey’s decision to notify Congress. They repeatedly said they did not believe that the FBI was likely to find evidence to support a prosecution. (Ex. A, IG Report, p. 352-355.)[7]

Notwithstanding the SSA’s awareness from the very outset of the need for probable cause to search the laptop, his knowledge of the prior history of the case, the absence of any necessity for, or direction to seek, a clean-up of spilled classified documents, and the knowledge that the entire focus of the new search authorized by Director Comey was the three months of “missing e-mails,” the ever-“aggressive” SSA purposefully executed a search warrant affidavit directed toward Secretary Clinton that was clearly intended to be misleading and pretextual. That the search warrant was sought on October 30, 2016, and made public by the FBI in contravention of long-standing DOJ policy not to interfere with an upcoming election, only makes the SSA’s conduct that much more egregious.[8]

The foregoing factual summary disposes of the FBI’s legal argument against disclosure. First, the Midyear SSA was not a low-level FBI employee, but rather an aggressive leader of the ill-fated Clinton e-mail investigation. He was involved in much of the high-level conversations and decision-making. His role was not merely to investigate and generate internal documents, but to discuss strategy and file in court an affidavit under oath setting forth probable cause for the most ill-advised search in FBI history. That the IG Report did not place specific blame on the SSA (Hardy Decl., ¶ 42) is hardly dispositive. The Report also did not absolve him of wrongdoing. Most of the rest of the leadership team, from Director Comey on down to Andrew McCabe, Lisa Page, Peter Strzok, Jim Baker, David Laufman, etc. have been fired, demoted or left the FBI. (Peter Strzok was fired on August 13, 2018.) The final chapter on this tragic saga has obviously not yet been written. The President and his right-wing allies continue to raise all sorts of spurious conspiracy theories with respect to Secretary Clinton’s e-mails.[9] If the Democrats regain control of the House of Representatives in November, further hearings can certainly be expected, to achieve full accountability for the wrongful decisions and actions of the FBI that interfered with the 2016 election. If nothing more, full public disclosure and transparency is absolutely necessary to rebut the deliberately false stories that are continuing to be generated by the President and his allies in the right-wing media.

III. ARGUMENT

A. The Public Interest in Disclosure Outweighs the Agents’ Privacy Interests Here.

The FBI’s heavy reliance on Lahr v. National Transportation Safety Board, 569 F.3d 964 (9th Cir. 2009) is misplaced. That case concerned low-level investigative agents and there was no suggestion that the agents had behaved improperly. Here, the SSA is obviously not “lower level,” but admittedly part of the “leadership of the team,” and there is ample evidence that the “aggressive” SSA actively participated in, and encouraged, an unnecessary, ill-timed search that was obtained without the necessary probable cause directed toward the evidence being sought. There are serious “doubts about the integrity of his efforts,” which greatly reduces the agent’s privacy interests. Castaneda v. United States, 757 F.2d 1010, 1012 (9th Cir. 1985). By contrast, the public interest in this matter is very high indeed. If the public has a right to know about the actions of Comey, McCabe, Strzok and Page – all of whom have testified before Congress on this matter – it has the right to know about the aggressive SSA, who, apparently, almost alone among the leadership team involved in this fiasco, still has his job. It cannot be an argument against disclosure that the agent may face public scrutiny for his actions, so long as it is clear, as it is in this case, that he very much deserves that scrutiny. Disclosure of the name of the SSA is warranted[10].

Whether to disclose the name of the Special Agent, in whose presence the inventory was made, is naturally a more difficult matter, as it is not possible for Plaintiff to identify him or his actions more specifically. Really the enormous public interest should be determinative. If that particular agent did nothing more than accept the inventory, then he also has little or nothing to fear from the passing disclosure of his name in the context of a matter that has already led to the demise of the FBI Director and numerous associates. If his role in procuring the improper search warrant was more pronounced, then the public should be made aware of that fact. The document was, after all, filed in court, and so the expectation of privacy is considerably diminished.

B. The Sealing Order Does Not Justify The FBI’s Refusal To Release The Information at Issue.

The FBI has consistently acted in bad faith, resisting disclosure throughout the course of Plaintiff’s efforts to release the search warrant. In December 2016, the FBI objected to any disclosure and then sought and obtained from the district court in New York redaction of large portions of the search warrant affidavit that it has only belatedly agreed to release in response to this lawsuit. (Compare Complaint, Ex. 4 with Hardy Decl., Ex. L.) Now it wants to use the New York court sealing order that it alone requested to thwart release of the last remaining items.

The FBI urges this court to ignore and refuse to follow an opinion from the D.C. Circuit, Morgan v. Dep’t of Justice, 923 F.3d 195, 198 (D.C. Cir. 1991) (“the mere existence of a court seal is, without more, insufficient to justify nondisclosure under the FOIA.”) (cited on the DOJ’s own website at https://www.justice.gov/oip/blog/foia-update-significant-new-decisions-22), distinguishing the obviously distinguishable Supreme Court opinion in GTE Sylvania, Inc. v. Consumers Union, 445 U.S. 375, 386 (1980). This isn’t difficult. GTE Sylvania concerned an injunction obtained by private parties (manufacturers) barring disclosure by the government of certain confidential reports. The Supreme Court held that it was not unreasonable for the government to comply with the injunction when faced with a FOIA request by a consumer group. In this case, and in Morgan, by contrast, there is no third party who has sought an injunction. Indeed, there is no injunction at all, only a sealing order. It was the FBI itself which sought the sealing order (and subsequently sought to modify it), and there is zero chance that the New York district court intended to bar the FBI from releasing the search warrant in response to a FOIA request. (See Castel Order, Exhibit 2 to Complaint, p. 9 (“the Court accepts the government’s proposed redactions of information regarding the criminal investigation into Subject 1 and information identifying the law enforcement personnel involved in the investigation of Secretary Clinton.”). It should be noted that the FBI cannot point to any specific wording in the New York court sealing orders that bars complete, unredacted disclosure of the document by the FBI in response to a FOIA request, and of course Plaintiff’s rights under FOIA were never at issue in those proceedings.[11] The FBI’s argument should be soundly rejected. Indeed, Plaintiff believes it would be appropriate for the Court, in the interest of the public, to order the FBI to cease and desist in this and all other matters from making the spurious and outrageously misleading legal claim in response to FOIA requests that “sealed court records are not eligible for release under the Freedom of Information Act.” (See Hardy Decl., ¶ 21, ¶ 25, Exhibit H, p. 48.)

This Court has the task of weighing the public’s right of access under FOIA with the purported privacy interests of the SSA, SA and Huma Abedin. Cameranesi v. Dep’t of Def., 856 F.3d 626, 637 (9th Cir. 2017). Here, the privacy interests for names and an already public e-mail address are certainly trivial. We are not talking about personnel files, records of disciplinary actions, unknown criminal investigations and the like. In the case of Abedin, a public figure, she cannot possibly expect to have any additional “embarrassment, harassment, or . . . mistreatment” above and beyond the maelstrom that has already landed upon her as a result of her completely innocent association with Hillary Clinton and Anthony Weiner. The implications for her personal privacy in the disclosure of her already public e-mail address are certainly trivial and de minimus. The public interest in having a historically important search warrant application unredacted outweighs any conceivable privacy interest. Similarly, for the two agents, and especially the SSA, their interest in avoiding association with the travesty that transpired, at their own hands, in October 2016, cannot possibly outweigh the public interest in exposing all of the details associated with this fiasco of a search. If the DOJ directive not to undertake actions to interfere with an election mean anything at all, it means not seeking a search warrant against a candidate for President under false pretenses within days of a national election, without any probable cause to believe that you will find what you are really seeking, and coming up empty-handed because the longed-for evidence never existed in the first place. An individual who does such a thing cannot possibly expect that he can remain anonymous and avoid public scrutiny.

C. The FBI Improperly Withheld Ms Abedin’s Email Address.

The final issue to be decided is whether the FBI should be permitted to keep the redaction of Huma Abedin’s Yahoo! e-mail address (presumably humamabedin@yahoo.com), about which articles were written by right-wing fringe outlets already in September and October 2016 thanks to disclosure by the Department of State.[12] Given how much the FBI has already willingly disclosed about Abedin, a public figure thanks to both her boss (Secretary Clinton) and infamous husband (Anthony Weiner), it seems a bit laughable to be terribly concerned about disclosing her already-revealed email address. Email addresses are, after all, not intended to be kept secret, since they are used to communicate with third parties, and in this case the address was also used for work-related e-mails while Abedin was at the State Department.[13]

IV. CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, Plaintiff respectfully requests that the Court DENY Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment, and GRANT summary judgment in favor of Plaintiff.

[1] . For the reasons set forth herein, the Court should not only deny Defendant’s motion, but the Court should sua sponte grant an order to show cause why summary judgment should not be granted in Plaintiff’s favor. It is well established that a court may grant summary judgment sua sponte in favor of a non-moving party so long as the party that had moved for summary judgment had reasonable notice that the Court might do so and so long as the party against whom summary judgment was rendered had “a full and fair opportunity to ventilate the issues involved in the motion.” Cool Fuel, Inc. v. Connett, 685 F.2d 309, 312 (9th Cir. 1982); Portsmouth Square, Inc. v. Shareholders Protective Comm., 770 F.2d 866 (9th Cir. 1985).

[2] Declaration of E. Randol Schoenberg (“Schoenberg Decl.”), Ex. A, Report issued on June 14, 2018 by the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Justice (“IG Report”). The initial referral to the FBI in 2015 was in fact not criminal in nature, but solely a clean-up operation. See Ex. A, IG Report, p. 41 (“[Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General Matt] Axelrod stated: ‘That, my recollection is that the way they explained it [the initial referral to the FBI in 2015] was that review of certain emails contained on the personal server that Secretary Clinton had been using showed that some of those emails contained classified information. And so that, and that they, one of the things that was sort of standard practice when there was classified information on non-classified systems was that a review needed to be done to sort of contain the, I think the word they use in the [intelligence] community is a spill…. The spill of classified information out into sort of [a] non-classified arena. And so that they needed to, this was a referral so that the Bureau could help contain the spill and identify if there was classified information on non-classified systems so that that classified information could be contained and either, you know, destroyed or returned to proper information handling mechanisms.’”).

The FBI has never properly explained how or why the investigation was converted to a criminal investigation, since there was never any indication of any criminal behavior. However, the FBI did decide that it would not seek a clean-up of the spill. See Ex. A, IG Report, p. 55 (“the Midyear team did not seek to obtain every device or the contents of every email account that it had reason to believe a classified email traversed.”); p. 93 (“Strzok further stated that the FBI’s ‘purpose and mission’ was not to pursue ‘spilled [classified] information to the ends of the earth’ and that the task of cleaning up classified spills by State Department employees was referred back to the State Department. He told us that the FBI’s focus was whether there was a ‘violation of federal law. Prosecutors 1 and 2 similarly told us that the Department was not conducting a spill investigation, and that the State Department was the better entity for that role. ‘At a certain point, you have to decide what’s your criminal investigation, and what is like a spill investigation…. [W]e could spend like a decade tracking emails…wherever they went.’ The SSA told us that the Midyear team engaged in several conversations, and the State Department officials expressed concern about the problem and were receptive to resolving it. Generally the witnesses told us that they could not remember anyone within the team arguing that more should have been done to obtain the senior aides’ devices.”); p. 167 (“[T]he picture that was fairly clear at that point [was] that Hillary Clinton had used a private email…to conduct her State Department business. And in the course of conduct [of] her State Department business, she discussed classified topics on eight occasions TS, dozens of occasions, and there was no indication that we had found that she knew that was improper, unlawful, that someone had said don’t do that, that will violate 18 U.S.C. [the federal criminal code], but that there was no evidence of intent and it’s looking, despite the fact of the prominence of it, like an unusual, but in a way fairly typical spill and that there was no fricking way that the Department of Justice in a million years was going to prosecute that.”); p. 374, n. 187 (“In his book, Comey stated, with respect to the July declination, that ‘[n]o fair-minded person with any experience in the counterespionage world (where “spills” of classified information are investigated and prosecuted) could think this was a case the career prosecutors at the Department of Justice might pursue. There was literally zero chance of that.’”).

[3] We feel compelled to add here that no one has ever explained what exactly such a hypothetical e-mail would say, why anyone would believe that Secretary Clinton would ever draft such an e-mail, or, most importantly, why the presence of such an e-mail would help prove a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 793(e) or (f), given all of the other facts developed in this investigation (notably the absence of any transmission or delivery of classified information to unauthorized recipients or the removal of such classified information by third parties). Note that the term “mishandling” appears nowhere in the criminal statute, and that communicating by e-mail does not “remove” anything.

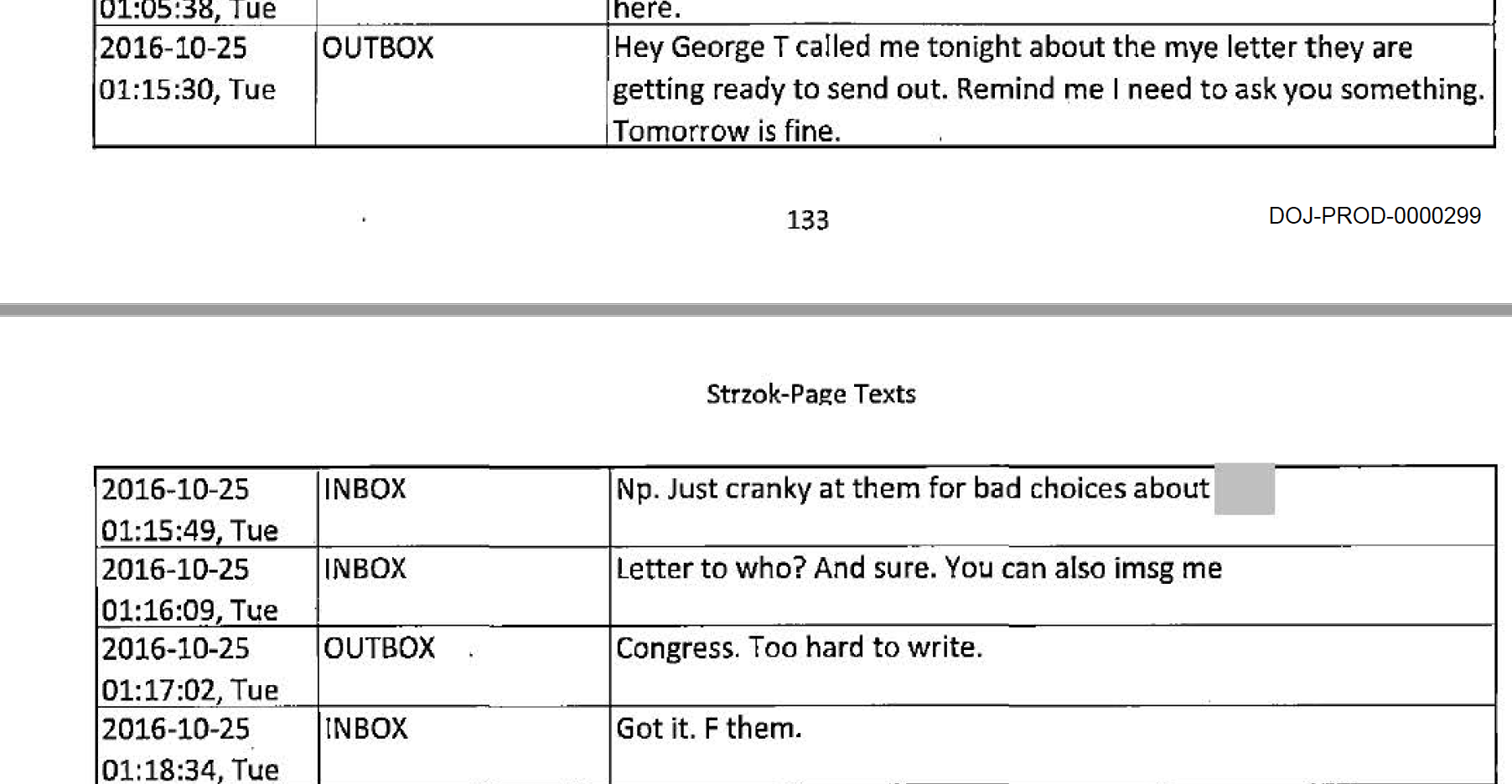

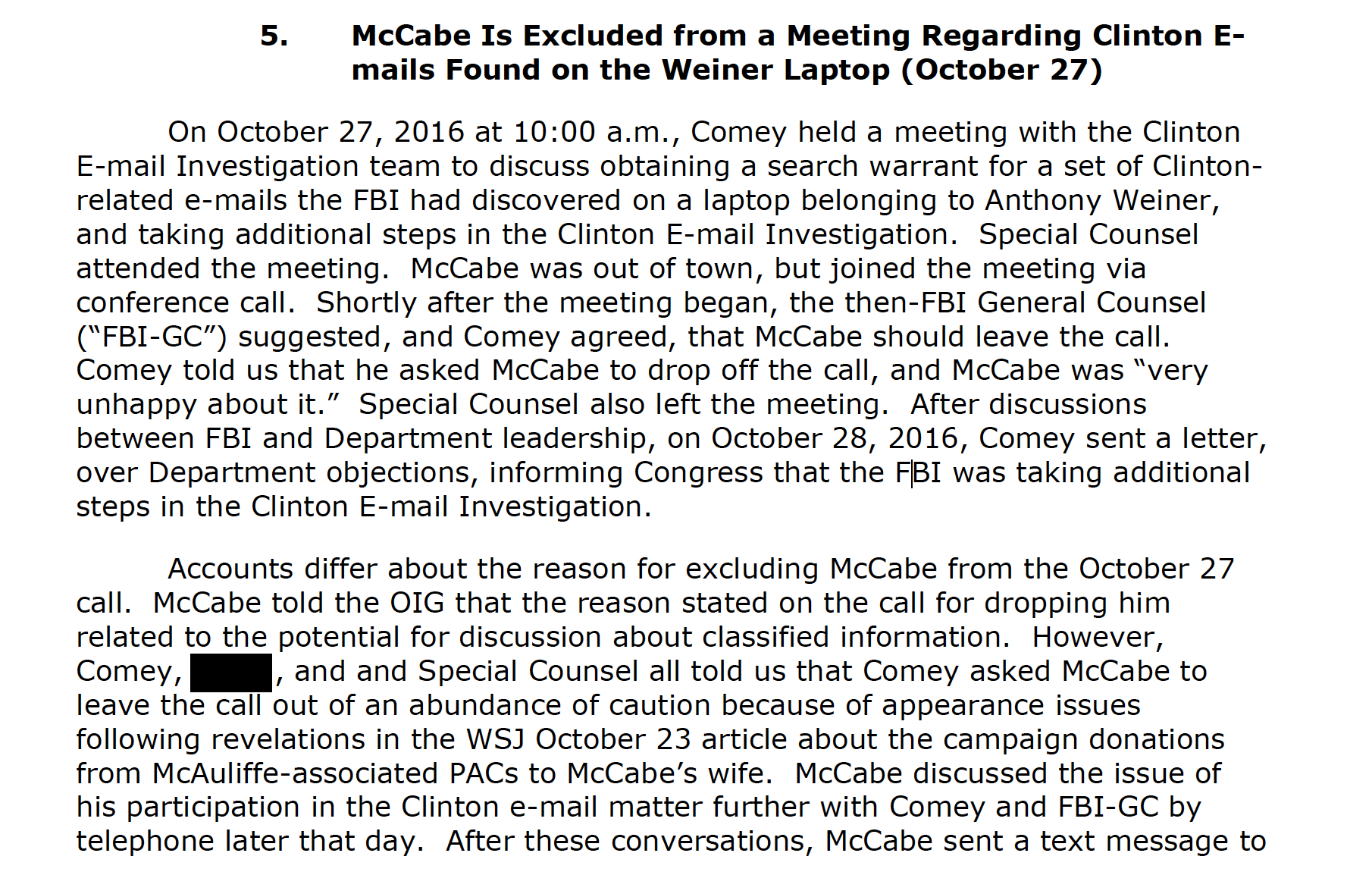

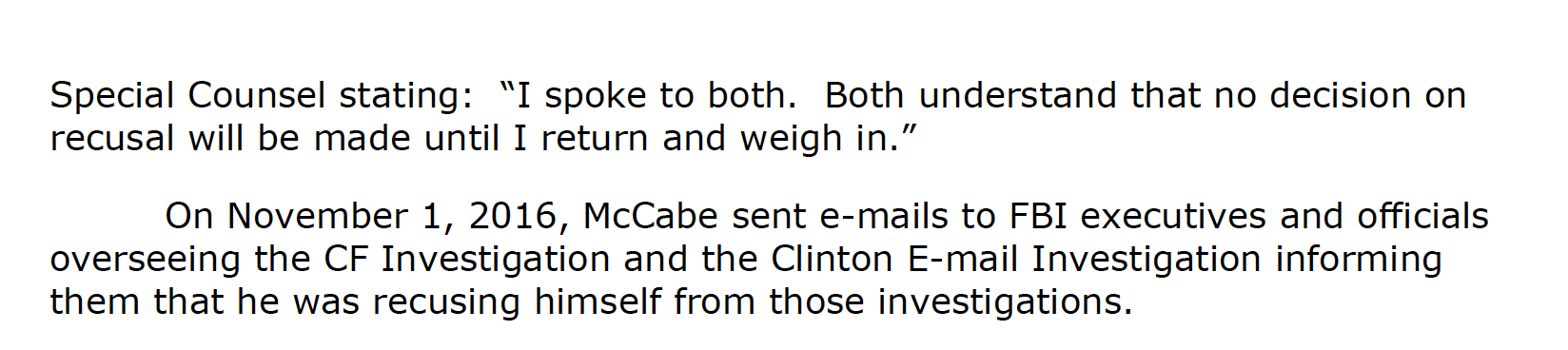

[4] Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, IG Report, p. 373; see also Schoenberg Decl., Ex. B, James Comey, A Higher Loyalty, p. 193 (“They told me those might well include the missing emails from the start of Clinton’s time at the Department of State. The team said there was no prospect of getting Weiner’s consent to search the rest of the laptop, given the deep legal trouble he was in. ‘We would like your permission to seek a search warrant.’ Of course, I replied quickly. Go get a warrant.”). At this fateful meeting, there appears to have been absolutely no discussion of whether there was probable cause to seek a warrant. Most likely this critical omission was because, at the outset of the meeting, Andrew McCabe and his counsel Lisa Page were excluded and removed from the meeting as fall-out from an October 24, 2016 Wall Street Journal article raising spurious claims of a conflict of interest because McCabe’s wife had once run for state office and received support from the governor of Virginia Terry McAuliffe, a friend of Hillary Clinton. See Schoenberg Decl., Ex. C, Office of the Inspector General U.S. Department of Justice, “A Report of Investigation of Certain Allegations relating to Former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe,” February 2018, pp 5-8, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2018/o20180413.pdf; Devlin Barrett, “Clinton Ally Aided Campaign of FBI Official’s Wife,” Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/clinton-ally-aids-campaign-of-fbi-officials-wife-1477266114

[5] Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, IG Report, p. 325, n. 178 (“Although Comey identified this fact as critical to his assessment of the potential significance of the emails on the Weiner laptop, the information was not included in the October search warrant application for the Weiner laptop.”)

[6] IG Report, p. 42 (“There were approximately 15 agents, analysts, computer specialists, and forensic accountants assigned on a full-time basis to the Midyear team, as well as other FBI staff who provided periodic support. Four WFO agents served as the Midyear case agents and reported to a WFO Supervisory Special Agent (‘SSA’). Several FBI witnesses described the SSA as an experienced and aggressive agent, and the SSA told us that he selected the ‘four strongest agents’ from his WFO squad to be on the Midyear team.”).

[7] Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, IG Report, p. 352-54, report of interviews with lead DOJ prosecutor David Laufman, Prosecutor 1 and Prosecutor 2:

We asked Laufman what he meant when he said there was a ‘low expectation’ that this evidence would alter the outcome of the Midyear investigation. Laufman stated:

[W]e had seen through our investigation, the types of emails that Huma Abedin had been party to. And they were just not the kinds of emails that really went to the core issues that were under legal analysis, meaning they had to do with sort of scheduling, and…I mean, as important as she is in a personal, confidential assistant manner to the former Secretary, she wasn’t as substantively engaged in, in some matters that would have occasioned access to classified information or dealing with classified issues. So…we had seen quite a bit up to that point. And with respect to her, we hadn’t seen her engaged via email with anybody on the types of things that were material to our legal analysis. So, assuming that what was going to be reviewed from this new dataset was consistent with that, it seemed improbable to us that it was going to, to change anything. And of course as we know now, it was a giant nothing-burger.

Prosecutor 1 stated that the notification to Congress “didn’t make any sense.” Prosecutor 1 told us that given Abedin’s role and the evidence they had previously reviewed there was little “likelihood of finding anything of import in there.” Instead of doing a public announcement, Prosecutor 1 stated, “We should just investigate it and do it as quickly as we could.” We asked Prosecutor 1 about the potential presence of BlackBerry emails from early in Clinton’s tenure.

Prosecutor 1 stated that the FBI mentioned that “there could be information that covered that BlackBerry period from the period at the front end of the tenure,” but added:

I felt like a lot of the analysis was based upon what, what could be in there and the opportunity cost of sort of missing out on that. Of course, to me that’s a different analysis than making an announcement about it. We didn’t want to be seen to be in favor of forgoing the effort entirely.

Prosecutor 1 stated that the FBI seemed “very concerned about transparency with the public” and “had already kind of decided what they were going to do” prior to consulting with the Department.

Prosecutor 2 told us that the Department was “shocked” that the FBI was even considering notifying Congress about this development. Prosecutor 2 said that she did not necessarily view the Weiner laptop as a significant development in the Midyear investigation. Prosecutor 2 stated:

Because over the course of this investigation, we haven’t sought out personal devices of anybody other than Hillary Clinton. So we haven’t asked, for example, for like Huma’s personal laptops, her personal BlackBerries. We have her state.gov stuff, but that’s like, that of Huma’s is all we’ve searched.

So, there’s a threshold question in my mind of whether, like, this is even something that needs to be searched. And based on the, the iffyness on that threshold question, and then the likely significance of this device, it seems totally nuts to me that they would make an announcement having no idea what is on this device, having not looked at it. And in, and in terms of like the impact that this announcement could have.

And I remember being on the phone call like, how are you, asking like how on earth are you going to word this announcement so it’s accurate and doesn’t, doesn’t like, you know, open a much bigger can of worms than is really the significance of this recent finding. I mean at this point…we have no idea…. We just know that like some of Huma’s emails are in FBI’s custody. Like, of course Huma has other emails. Like, how is this a game changer?

Prosecutor 2 also told us that she believed the FBI would not listen to any of the arguments they put forth. She stated, “[T]here’s a defeated feeling at this point that like [Strzok] was given the task of like pretend to DOJ that you’re hearing them out. And he was going to, you know, humor us by having this conference call, but like that nothing we said mattered on that call.

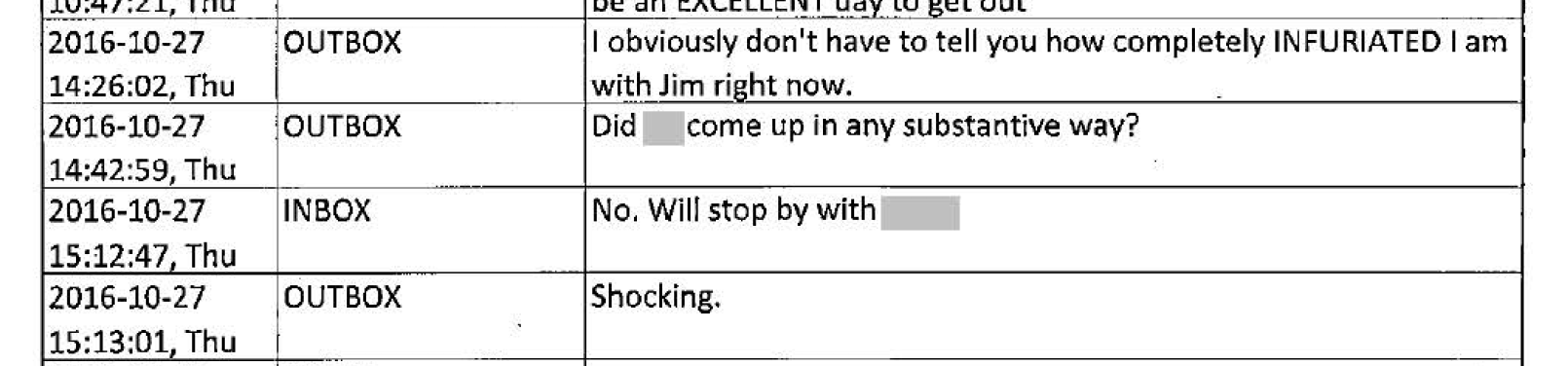

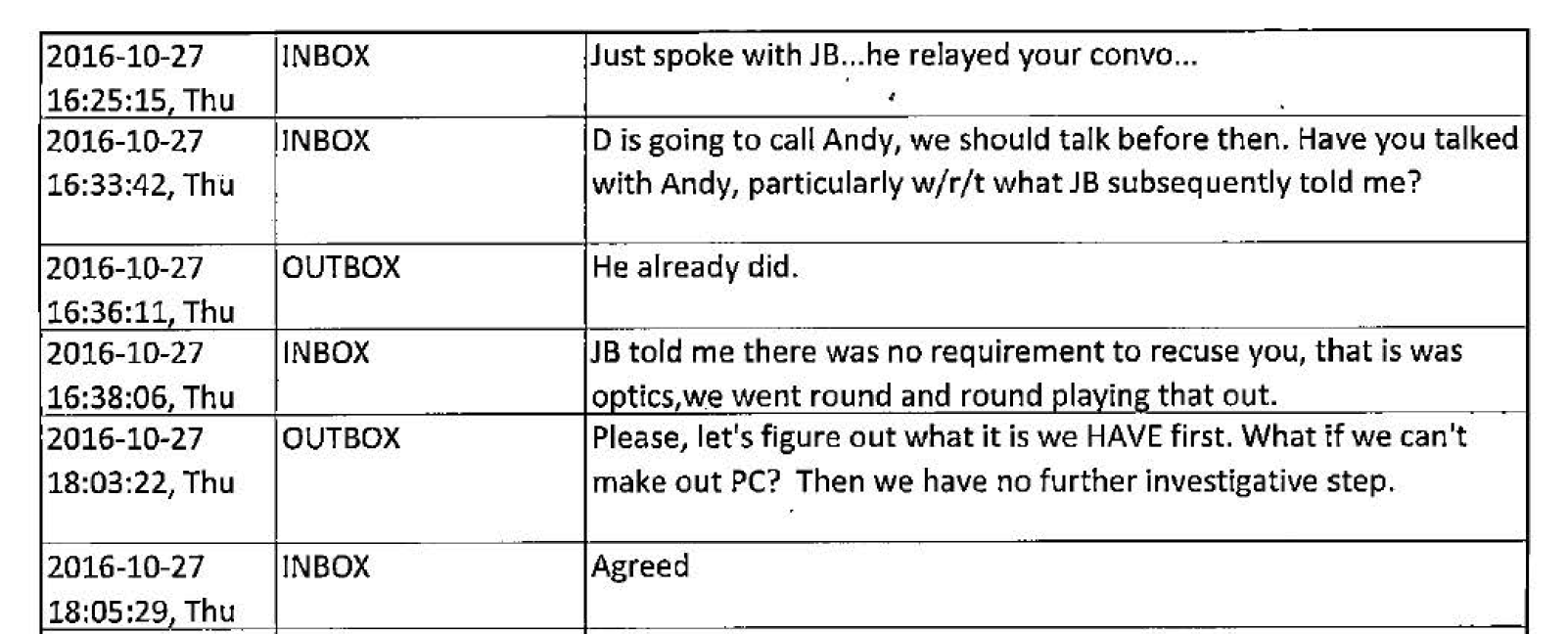

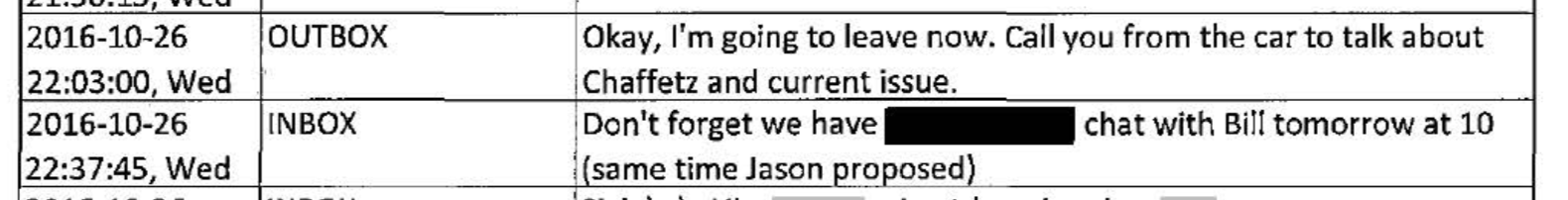

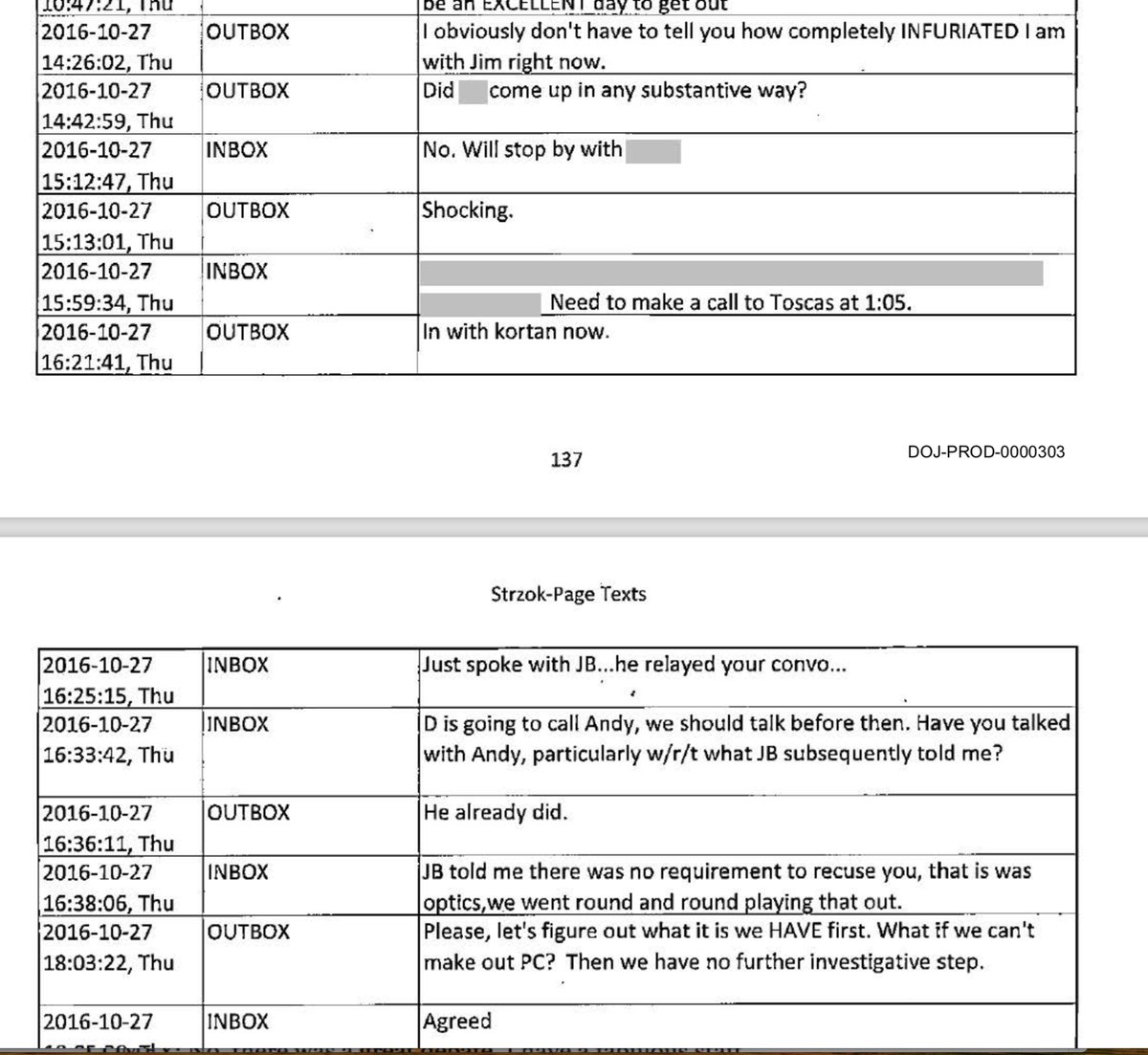

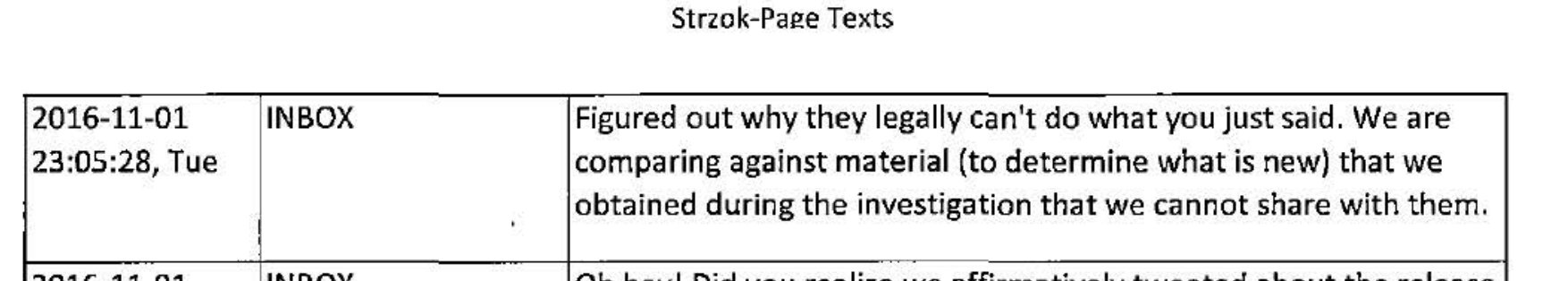

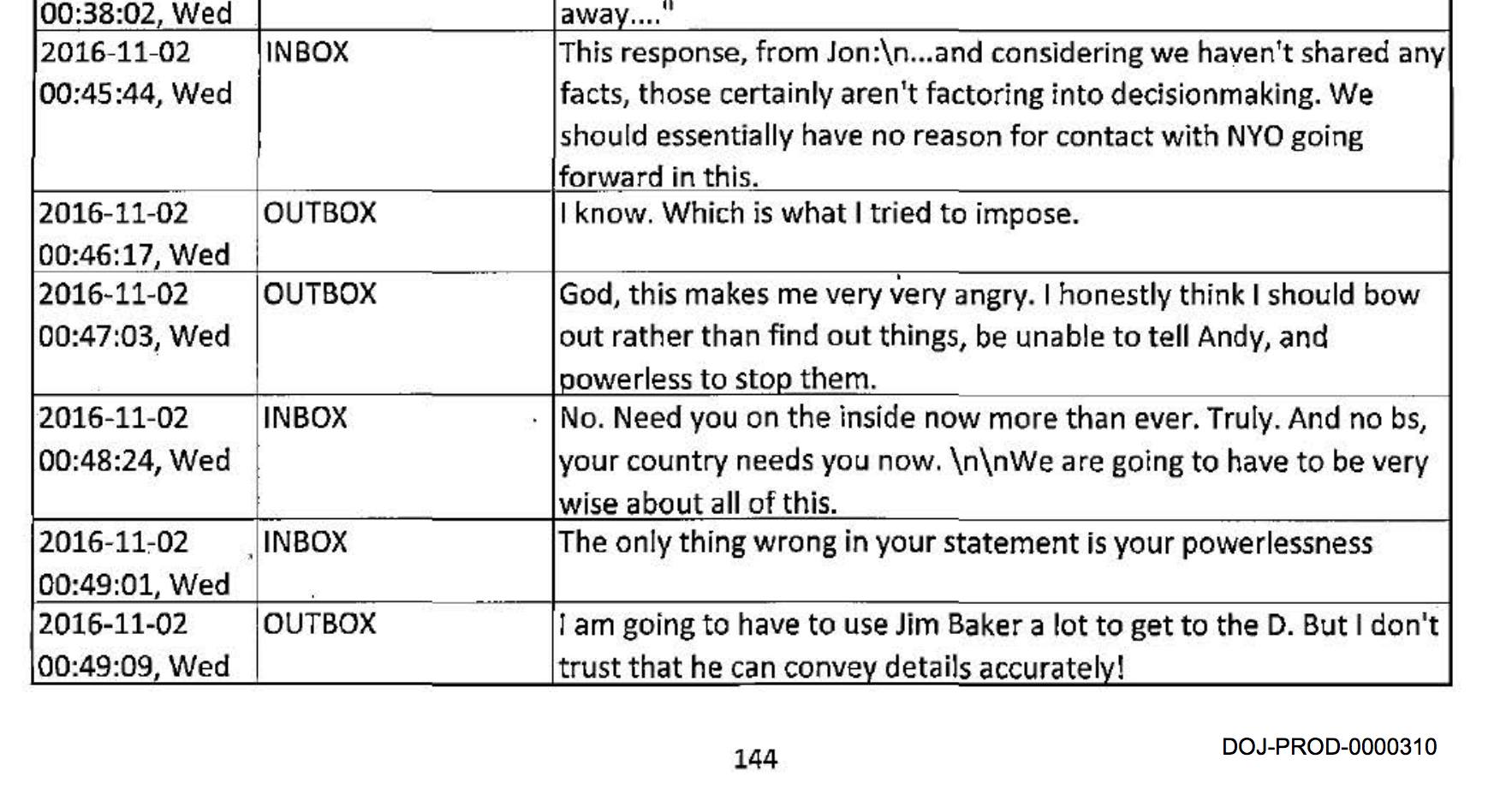

If there is one as-yet unnoticed undercurrent or subtext in all of the released information concerning the FBI’s investigation of Secretary Clinton, it is the apparent unwillingness of the male FBI leadership and agents to heed the warnings of their female colleagues, and the apparent understanding of these female colleagues that their views would not be followed by the men. See, e.g., Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, IG Report, p. 377, (Attorney General Loretta Lynch and Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates were afraid to speak directly to Comey because he didn’t consult with them) (“We acknowledge that Comey, Lynch, and Yates faced difficult choices in late October 2016. However, we found it extraordinary that Comey assessed that it was best that the FBI Director not speak directly with the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General about how to best navigate this most important decision and mitigate the resulting harms, and that Comey’s decision resulted in the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General concluding that it would be counterproductive to speak directly with the FBI Director.”); IG Report, p. 340-42 (FBI Deputy Counsel Trisha Anderson and FBI Attorney 1 try unsuccessfully to remind Comey and FBI General Counsel Jim Baker that they were about to interfere in the election) (“I gather he [Baker] thought she [Anderson] might not raise it. So at our next family discussion that evening, he said let me ask you a contrarian question. You know how do you think about this? And then I think she spoke herself and said, how do you think about the fact that you might be helping elect Donald Trump? And I said, I cannot consider that at all.”) (“Baker told us that he asked Anderson if she wanted to bring this up with Comey, but Baker stated that ‘she was reticent’ to do so.”); Complaint, Ex. 7, text message from FBI attorney Lisa Page to FBI agent Peter Strzok on October 27, 2016 (FBI Attorney Lisa Page tries to remind FBI Agent Lead Peter Strzok that they cannot search the laptop without probable cause) (“completely INFURIATED [ ] with [FBI general counsel] Jim [Baker]…. Please, let’s figure out what it is we HAVE first. What if we can’t make out PC [probable cause]? Then we have no further investigate step.”).

[8] The IG Report includes a full Chapter on the drafting of the search warrant but unfortunately does not address the obviously pretextual nature of the affidavit. Schoenberg Decl., Ex. A, IG Report, pp. 379-84. Indeed, if there can be any valid criticism of the IG Report it is the illogic of its analysis of the search warrant and its aftermath. For example, The IG writes: “We found the belief that the Weiner laptop was unlikely to contain significant evidence to be an insufficient justification for neglecting to take action on the Weiner laptop immediately after September 29.” Ex. A, IG Report, p. 327. Really? Since when is it “unjustified” to decide not to obtain a search warrant to look for non-existent evidence that no one believes is there? The IG Report briefly describes the ultimate review of the emails on the Weiner laptop, but fails to mention that absolutely no emails were found from the early three-month time period that Comey and the others believed might be important. Compare Ex. A, IG Report, pp. 388-89; Ex. A, Comey, Higher Loyalty, p. 202 (“There were indeed thousands of new Clinton emails from the BlackBerry domain, but none from the relevant time period.” (Emphasis added.)). In fact, as anyone with even a limited knowledge of the case would expect, all 13 of the classified email chains that were found on the laptop were duplicates of those already reviewed previously. Ex. A, IG Report, p. 389. Perhaps the drafters of the IG Report were not technically proficient enough to ask the crucial question — when did the FBI agents and technicians reviewing the emails learn that absolutely no emails from the sought-after three-month time frame were on the laptop? No doubt that fact could have been discovered almost immediately, and if it was, then what exactly was the FBI looking for over the course of the ensuing week, while the upcoming election hung in the balance? Or were they simply stalling to cover for the fact that they had made a huge blunder? The IG Report is silent on these crucial questions.

[9] See most recently the August 28, 2018 Tweet by Donald J. Trump alleging that Clinton’s e-mails “got hacked by China,” at https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1034654816046329856; compare “FBI pushes back on unfounded Trump claim that China hacked Hillary Clinton’s e-mail,” Washington Post, August 29, 2018 at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-without-citing-evidence-says-china-hacked-hillary-clintons-emails/2018/08/29/cdbd6c60-ab71-11e8-8a0c-70b618c98d3c_story.html?utm_term=.2384bb3b96af. (Schoenberg Decl., Ex. F)

[10] See Lissner v. U.S. Customs Service, 241 F.3d 1220, 1223 (ordering disclosure of physical description of state law enforcement officers, and citing only general public interest in ensuring reliability of government investigation); Hardy v. FBI, No. 95-883, slip. op. at 21 (D. Ariz. July 29, 1997) (releasing identities of supervisory ATF agents and other agents publicly associated with Waco incident, finding that public’s interest in Waco raid “is greater than in the normal case where release of agent names affords no insight into an agency’s conduct or operations.”); Butler v. DOJ, 1994 WL 55621 at 13 (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 1994) (releasing identities of supervisory FBI personnel upon finding of “significant” public interest in protecting requester’s due process rights); Weiner v. FBI, No. 83-1720, slip op. at 7 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 6, 1995) (finding public interest in release of names and addresses of agents involved in management and supervision of FBI investigation of music legend John Lennon).

[11] Similarly, it is not a remedy to suggest, as the FBI does, that Plaintiff seek a modification of the sealing order in the New York district court, since FOIA would not be available in such an action.

[12] See https://www.wnd.com/2016/09/hillarys-chief-of-staff-used-personal-email-for-state-business/ and https://www.wnd.com/2016/10/yahoo-holds-key-to-fbi-probe-of-hillary-huma-emails/) and again in January 2018 (see http://dailycaller.com/2018/01/01/abedin-forwarded-state-passwords-to-yahoo-before-it-was-hacked-by-foreign-agents/ and https://davidharrisjr.com/politics/huma-abedins-personal-yahoo-account-hacked-forwarded-sensitive-material/). (Schoenberg Decl., Exs. G)

[13] Perhaps it is worth noting that the FBI had no qualms about disclosing not only Plaintiff’s e-mail address but his residence address and telephone numbers in the context of its filing in this matter. See Hardy Decl., Ex. E, p. 33.