Since this week the media was “all Comey, all the time” — thanks to the publication of his book, Higher Loyalty, and the release of his memos about his meetings with Donald Trump — I might as well record my thoughts as well.

I am focused on just one aspect of Comey’s legacy, namely his fateful decision on Thursday, October 27, 2016 to allow the FBI to obtain a search warrant to look at e-mails between Hillary Clinton and her aide Huma Abedin that were found on Anthony Weiner’s laptop. I have called this decision “the biggest mistake in the history of mistakes” and I still stand by that characterization. There is really no serious doubt that Comey’s decision changed the outcome of the election and helped elect Donald Trump. Benjamin Wittes has recently argued that the difference between Trump’s chances of winning, as calculated by Nate Silver, on October 27 (20%) and November 8 (28%), are too close to make that determination, but he doesn’t really grapple with the stats, and the fact that, according to Silver, Trump’s chances narrowed to as close as 35% on Sunday, November 6, when the FBI announced that the e-mail search revealed nothing incriminating. The predictors are of course imprecise, but the outcome of this particular election can be explained by the fact that, as my college friend Ed Glaser has argued, information travels less quickly in rural areas, like those in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, where Trump managed to hold on to a very, very narrow victory. Even with the FBI email debacle, had the election happened one or two days later, Clinton almost certainly would have won, as the public sentiment gradually returned to where it was on October 27.

The other reason that I focus on Comey’s mistake is that he has yet to admit he made a mistake. In fact, he continues to claim that if he had it to do all over again, he would make the same decision. “I am convinced that if I could do it all again, I would do the same thing, given my role and what I knew at the time.” (Page 207.) Many people have focused on the ridiculous “Speak or Conceal” dichotomy that Comey has set up in his mind to explain away his error. He seems simply incapable of applying the actual facts as they developed to help him see that a different, and very justifiable, decision would have been preferable. The most he offers is this:

Another person might have decided to wait to see what the investigators could see once they got a search warrant for the Clinton emails on Anthony Weiner’s computer. That’s a tricky one, because the Midyear team [the FBI team working on the e-mails] was saying there was no way to complete the review before the election, but I could imagine another director deciding to gamble a bit by investigating secretly in the week before the election. That, of course, walks into Loretta Lynch’s point after our awkward hug. Had I not said something, what was the prospect of a leak during that week? Pretty high. Although the Midyear team had proven itself leakproof through a year of investigation, people in the criminal investigation section of the FBI in New York knew something was going on that touched Hillary Clinton, and a search warrant was a big step. The circle was now larger than it had ever been, and included New York, where we’d had Clinton-related leaks in prior months. Concealing the new investigation and then having it leak right before the election might have been even worse, if worse can be imagined. But a reasonable person might have done it.

Obviously, Comey is simply incapable of imagining the world as it would have been had he made a different choice. What could he possibly mean by “might have been even worse”? Worse than what actually transpired? Worse than his firing by President Trump? What exactly is he imagining that would be worse? Really, what is it?

I think Comey is imagining something that he knows now isn’t true, but that he really thought would be true when he made the decision on October 27. Comey thought the FBI was going to find something incriminating. He really did. It is the only way to understand his decision-making then, and his attempt to justify it now. What he was deathly afraid of was that Clinton would win and then afterwards it would be revealed that she had actually committed a crime. In that scenario, the wrath of the world that he lived in — almost exclusively Republican — would have come squarely down on his head. That was the scenario he most feared, and that he most wanted to avoid. That was why the “Conceal” door, as he describes it, looked so threatening. He didn’t see that inside that door was another, much more likely scenario — that the FBI would find nothing incriminating on the laptop, making his failure to disclose the new search both harmless and easy to explain. The Conceal door only becomes scary if you think the chance of finding incriminating evidence was higher than the chance of not finding any. Comey thought Clinton was guilty, and that the FBI would find, as he called it in his Senate testimony, the “golden e-mails” proving her guilt, that had eluded them so far.

Let’s go back and look at the days leading up to Comey’s October 27 decision to see how a series of events led to this his calamitous decision.

The emails on the Weiner laptop were first discovered in early October. Andrew McCabe, the deputy director in charge of the “Midyear Exam” team (as the email review team was called), mentioned the new e-mails to Comey at the time, but neither of them seems to have taken it too seriously. After all, Huma Abedin’s e-mails, both the ones stored at the State Department and those voluntarily delivered to the FBI by Abedin’s lawyers, had already been carefully reviewed by the FBI and nothing incriminating had ever been found.

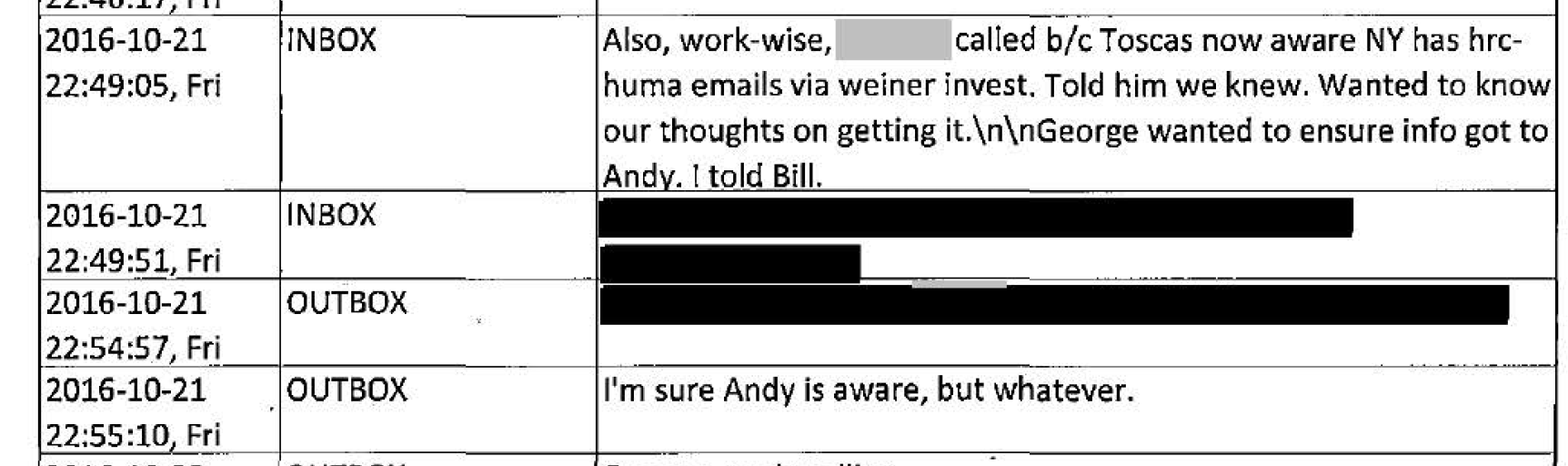

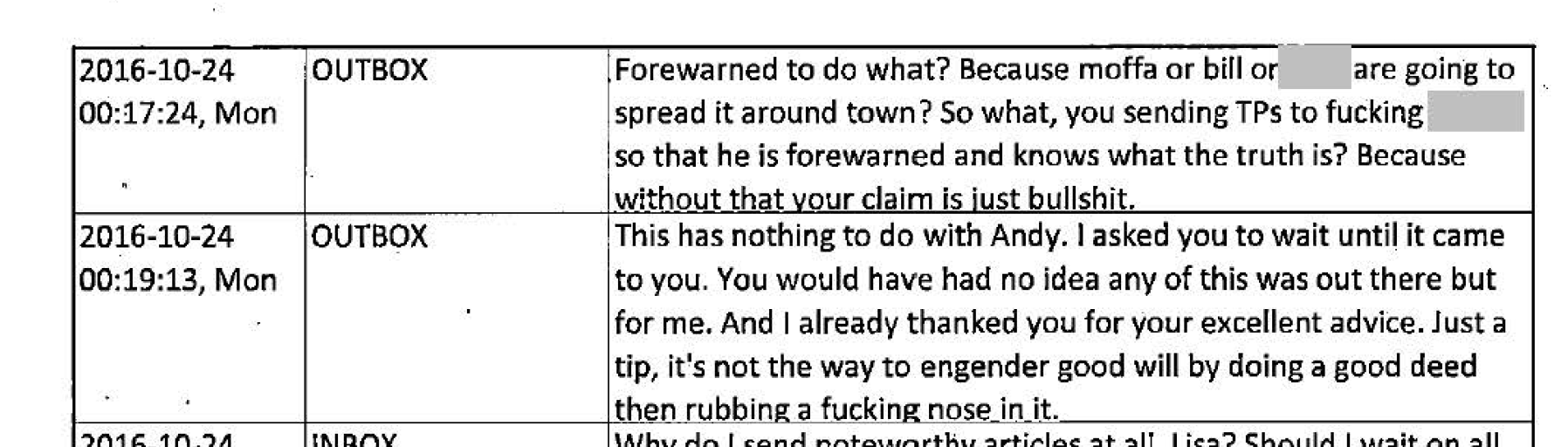

On October 21 an associate of George Z. Toscas, a national security prosecutor at the Department of Justice, asked FBI agent Peter Sztrok about the Weiner laptop. Sztrok texted to FBI attorney Lisa Page, assigned to McCabe, about Toscas’ inquiry:

So the renewed focus of on the laptop e-mails came from Toscas at the Justice Department. This is the catalyst for everything else that transpired and we do not know yet why Toscas was making the inquiry.

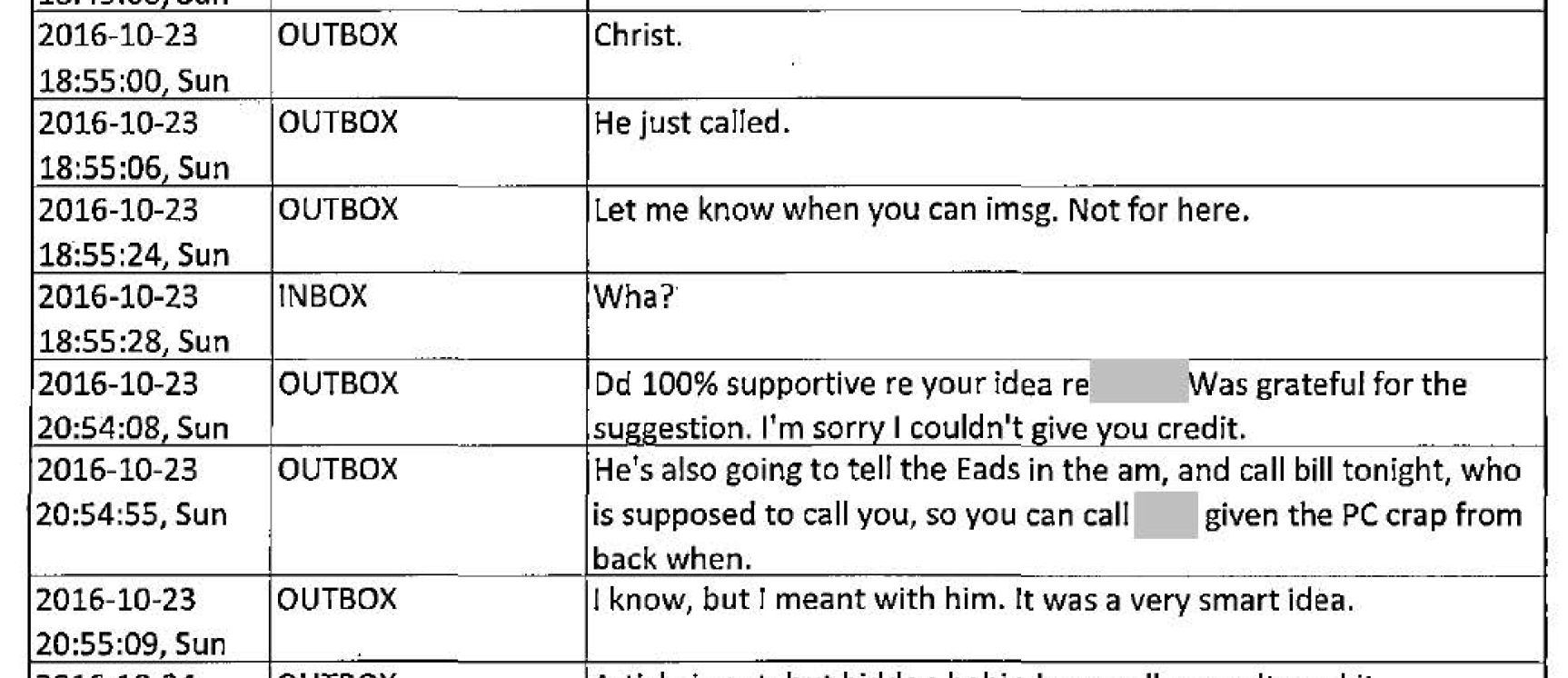

On Sunday, October 23, Sztrok and Page text about an impending story on Andrew McCabe in the Wall Street Journal .

Bill is Bill Priestap, FBI Assistant Director of Counterintelligence. EAD means Executive Assistant Director, so apparently Andrew McCabe was planning on telling Priestap about the WSJ story that evening and everyone else on Monday morning. What is also interesting is that Page refers to “the PC crap from back when.” PC stands for “probable cause,” the constitutional standard for obtaining a search warrant. More on that later.

Around midnight that evening, the article by Devlin Barrett for the Wall Street Journal appeared online with the headline “Clinton Ally Aided Campaign of FBI Offcial’s Wife.” In a classic, attenuated guilt-by-association, Devlin suggested that McCabe had a conflict of interest because his wife’s campaign received funds from an old friend of Clinton. The implication was that McCabe, who had been elevated to his position after his wife’s campaign had already ended, was somehow conflicted in his role overseeing the Clinton e-mail investigation. We don’t know how Barrett came to write the story, but it certainly looks like it was planted by someone supporting the Trump campaign.

Immediately Sztrok and Page have a spat by text over Sztrok’s desire to share the WSJ article with everyone right away. In her replies, Page implies that some of the other team members, including Bill Priestap, Jonathan C. Moffa of the FBI’s criminal division and Office of General Counsel, and someone whose name is redacted, would be eager to “spread it around town.”

So we have a sense from this that Page thought that some of the Midyear team members might not like McCabe and would want to damage his reputation by sharing the WSJ article.

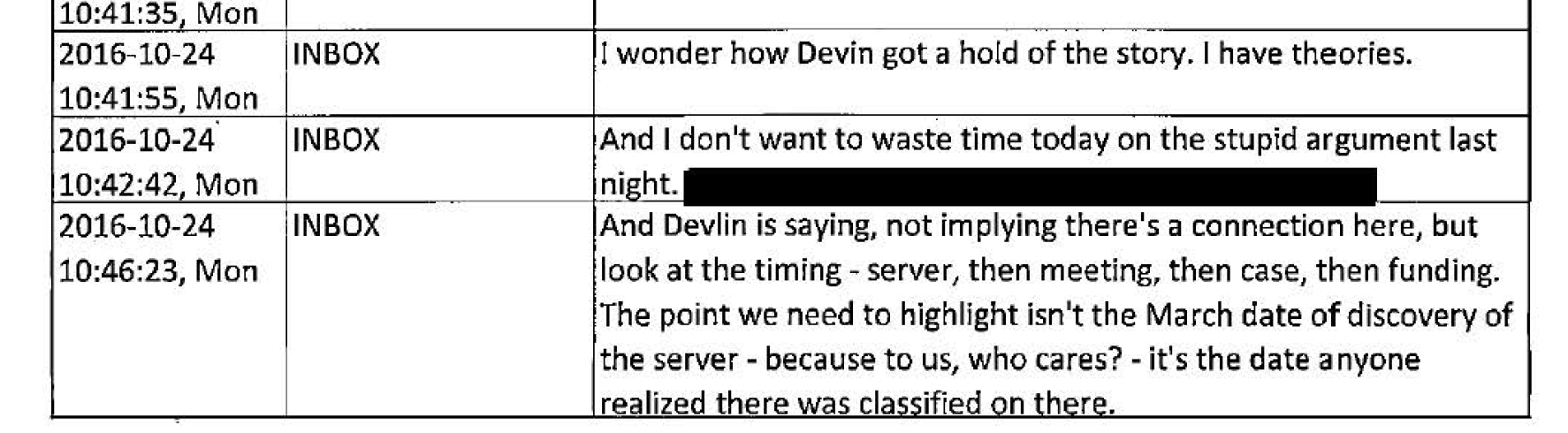

Sztrok and Page are clearly on McCabe’s side, and on Monday morning Sztrok sends Page some ideas of how to respond to Devlin Barrett’s WSJ article. Like me, Sztrok wonders how he got the story. He has his suspicions and I’d love to know what they were.

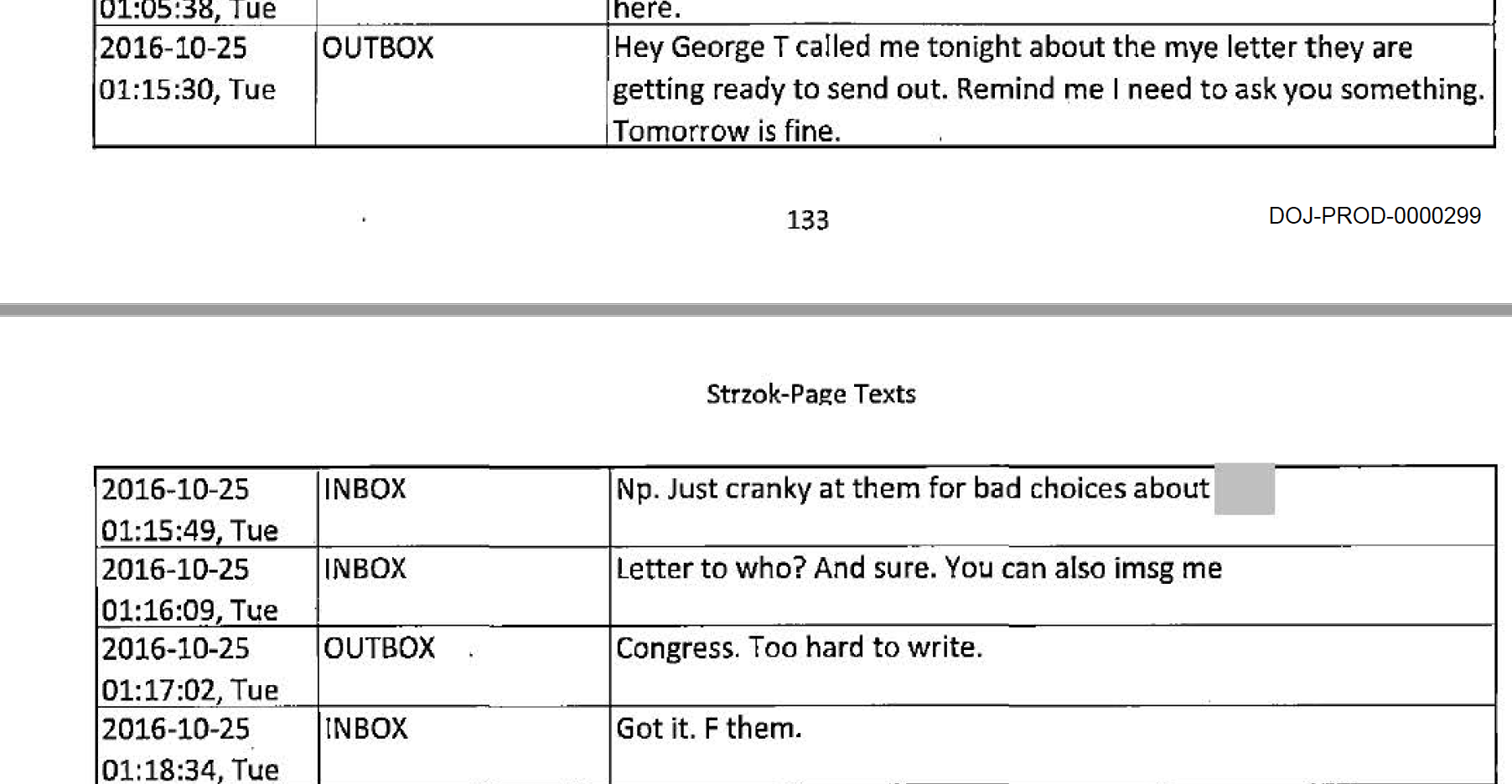

On Tuesday, October 26, things are starting to move again on the Clinton e-mail case. I am not sure if anyone outside conservative media has reported on it, but as I write this it looks to me like George Toscas and the Department of Justice were preparing to send a letter to Congress about the e-mail investigation. “MYE” is Midyear Exam, the code name of the Clinton e-mail investigation.

A letter was sent on October 31, but by then a lot of water had gone under the bridge and it doesn’t seem to say much of anything.

Page and McCabe have a call late at night on October 26, and just after midnight Page texts Sztrok about a meeting of the Clinton e-mail team being set up for the morning. Comey says he got an e-mail from McCabe at 5:30am about the meeting, but apparently McCabe, who was out of town at the time, didn’t even tell Comey what it was about.

The big meeting takes place at 11:00am on Thursday, October 27, with McCabe, the team supervisor, on the telephone. (Note: the Inspector General Report on Andrew McCabe says 10:00am, but Page is blithely texting Sztrok about lunch and things until 10:47am, so I think they got the time wrong.) Comey describes the meeting as follows:

I walked into my conference room and smiled broadly at the team leaders, lawyers, and executives from the Midyear case, each sitting in the same seats they had occupied so many times in the year of the Clinton email investigation. “The band is back together,” I said, as I slid into my seat. “What’s up?” It would be a long time before I smiled like that again.

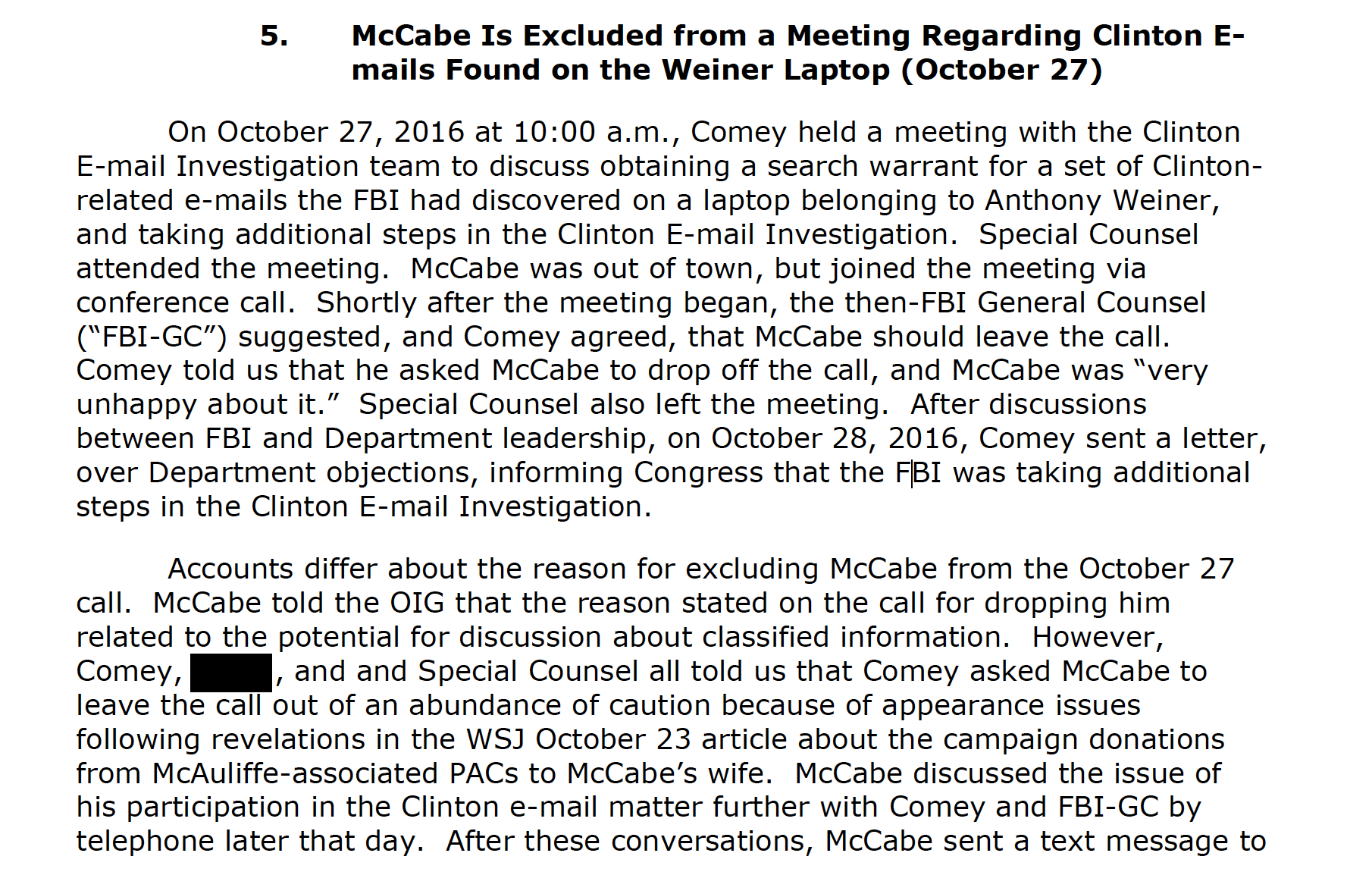

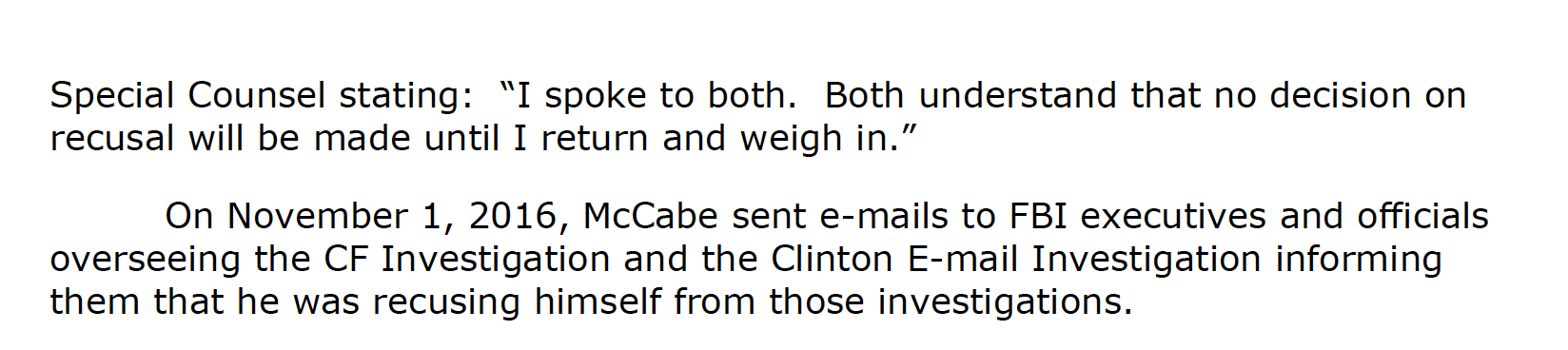

In his book, Comey doesn’t mention the very important event that happened next. But the Inspector General report concerning Andrew McCabe that was released last week tells the story.

So, based on the advice of FBI General Counsel Jim Baker, both Andrew McCabe, the supervisor of the team and the one who had called the meeting, and his special counsel Lisa Page, were excluded from the deliberations about what to do about the Weiner laptop. Neither of them knew they were going to be excluded. It was a coup.

After McCabe and Page left the meeting, the team informed Comey about the issue with the laptop. According to Comey, they told him that the laptop held thousands of emails from the AT&T Blackberry domain that Clinton used before setting up her private server. Comey has said these were important to him because they might include e-mails showing that Clinton purposefully set up her private email server, knowing that she wasn’t supposed to do that under State Department guidelines. (Whether or not even that would constitute a crime is very questionable, by the way, but Comey apparently believed it would.) “They told me those might well include the missing emails from the start of Clinton’s time at the Department of State. The team said there was no prospect of getting Wiener’s consent to search the rest of the laptop, given the deep legal trouble he was in.” (p. 193) Then comes the fateful moment:

“We would like your permission to seek a search warrant.”

Of course, I replied quickly. Go get a warrant.

And that was it. Without any reflection or discussion of whether or not there was probable cause to believe Clinton had committed a crime, Comey authorized his team to seek a search warrant against a candidate for President, twelve days before an election. Of course.

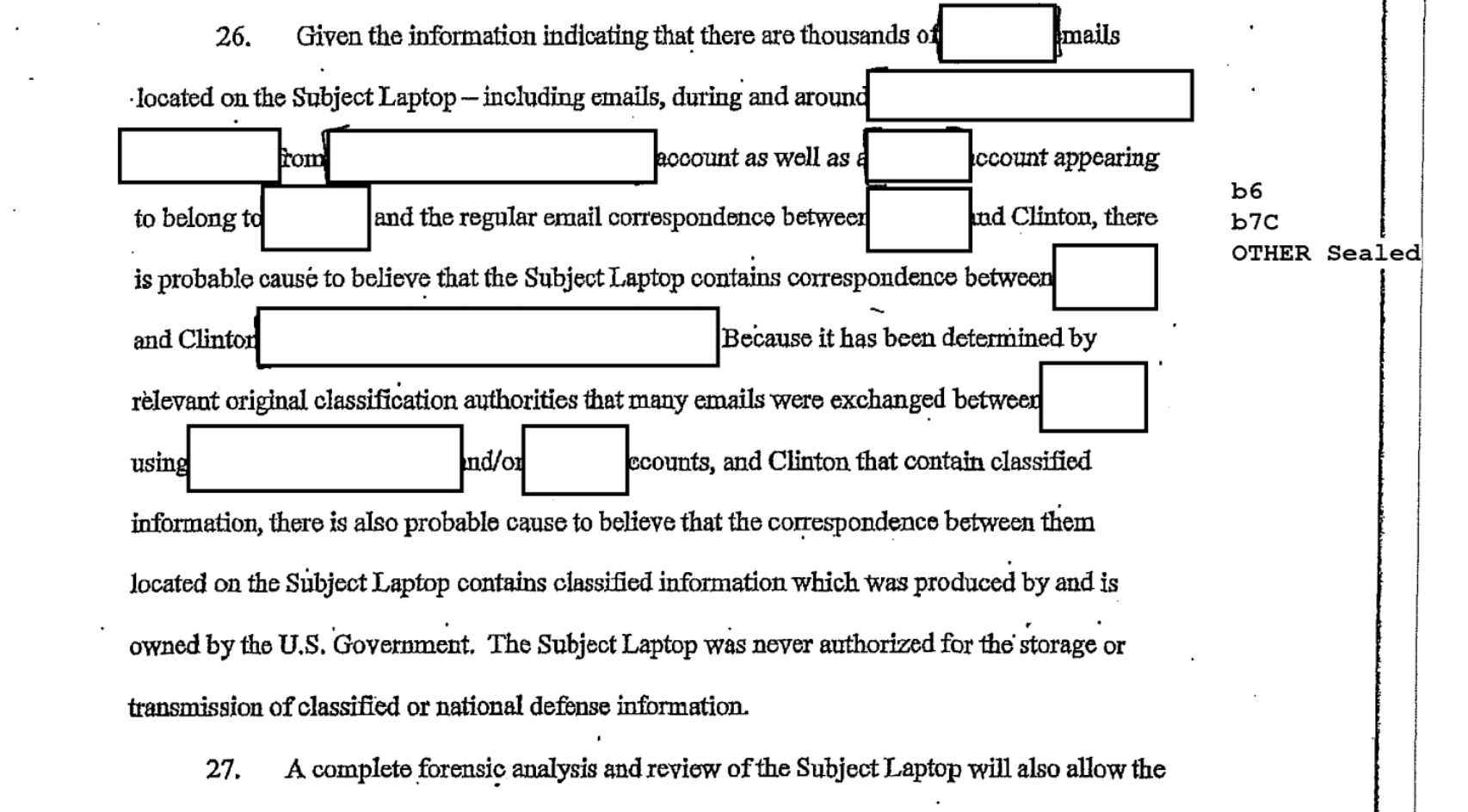

It is hard to exaggerate how incredibly serious that decision was. Until that moment, the FBI had not obtained a search warrant in the investigation, which had begun not as a criminal investigation, but as a security review of the e-mails to confirm their classification and make sure they had not been improperly accessed, requested by the Inspectors General of the Intelligence Community and the State Department, who were fighting over jurisdiction in July 2015 (as described in detail in Lanny Davis’s book “The Unmaking of the President 2016“). On July 5, 2016, Comey had said that “we cannot find a case that would support bringing criminal charges on these facts.” Suddenly, and without any further evidence, it had become “probable” that the FBI would find evidence on Weiner’s laptop of a crime by Clinton. How?

I’ve followed Comey closely since November 2016 and I’ve watched a lot of his interviews this past week. He’s never been asked why he thought there was probable cause to believe the FBI would find evidence of a crime on that laptop. I think that if asked, he’d say that he had no idea what was on the laptop, and no idea if anything would be incriminating. He’d probably say he thought it was possible. But he couldn’t admit he thought it was probable, which is something very different, because he had not yet seen any evidence to support that belief. Yet I think the truth must be that he really did believe, despite all the evidence that had been reviewed, that it was probable that Clinton had committed a crime. And so he didn’t even give it a second thought.

The rest of the meeting concerned what to do next. The team (without McCabe and Page) told him that it would take weeks to review the emails. They were wrong, stupidly wrong. There were in fact no emails on the laptop from the time frame that supposedly motivated the search. As Comey reports in his book, “There were indeed thousands of new Clinton emails from the BlackBerry domain, but none from the relevant time period.” (p. 202) None. Zero. Zilch. Nada.

By now, Comey has discussed ad nauseam the thinking that led him to decide to disclose the laptop search immediately by sending a letter to Congress. As I have said, he and the remainder of the Midyear team had an obvious blind spot to the likelihood that they would quickly know that there were no relevant emails on the laptop. Comey has testified that just one person, who has been described as a female “junior lawyer”, questioned whether he should worry about affecting the election. I believe that person was Lisa Page, but then supposedly she was excluded from the big meeting. So I am not sure. Maybe this was at a subsequent meeting.

As we were arriving at this decision, one of the lawyers on the team asked a searing question. She was a brilliant and quiet person, whom I sometimes had to invite into the conversation. “Should you consider what you are about to do may help elect Donald Trump president,” she asked?

I paused for several seconds. It was of course the question that was on everyone’s mind, whether they expressed it out loud or not.

I began my reply by thanking her for asking that question. “It is a great question, ” I said, “but not for a moment can I consider it. Because down that path lies the death of the FBI as an independent force in American life. If we start making decisions based on whose political fortunes will be affected, we are lost.”

Comey was spectacularly wrong on this point, and he has yet to understand or admit his error. The rule is that the FBI should affirmatively avoid interfering with elections, when possible, not that it should be agnostic. Comey chose to be agnostic. He refused to consider whether his actions would interfere with the election. The choice that Comey had was not Speak or Conceal, but Interfere or Not Interfere. He should have chosen not to interfere. It really is that simple.

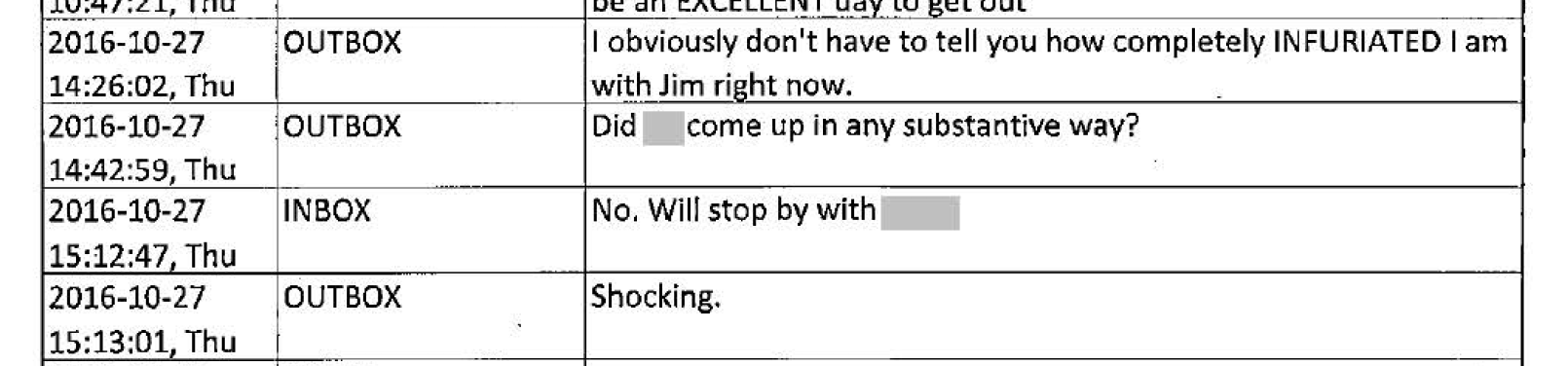

Lisa Page was obviously not happy about being excluded from the big decisions being made on the investigation she had helped McCabe supervise. She texted to Sztrok later that she was furious with her boss Jim Baker.

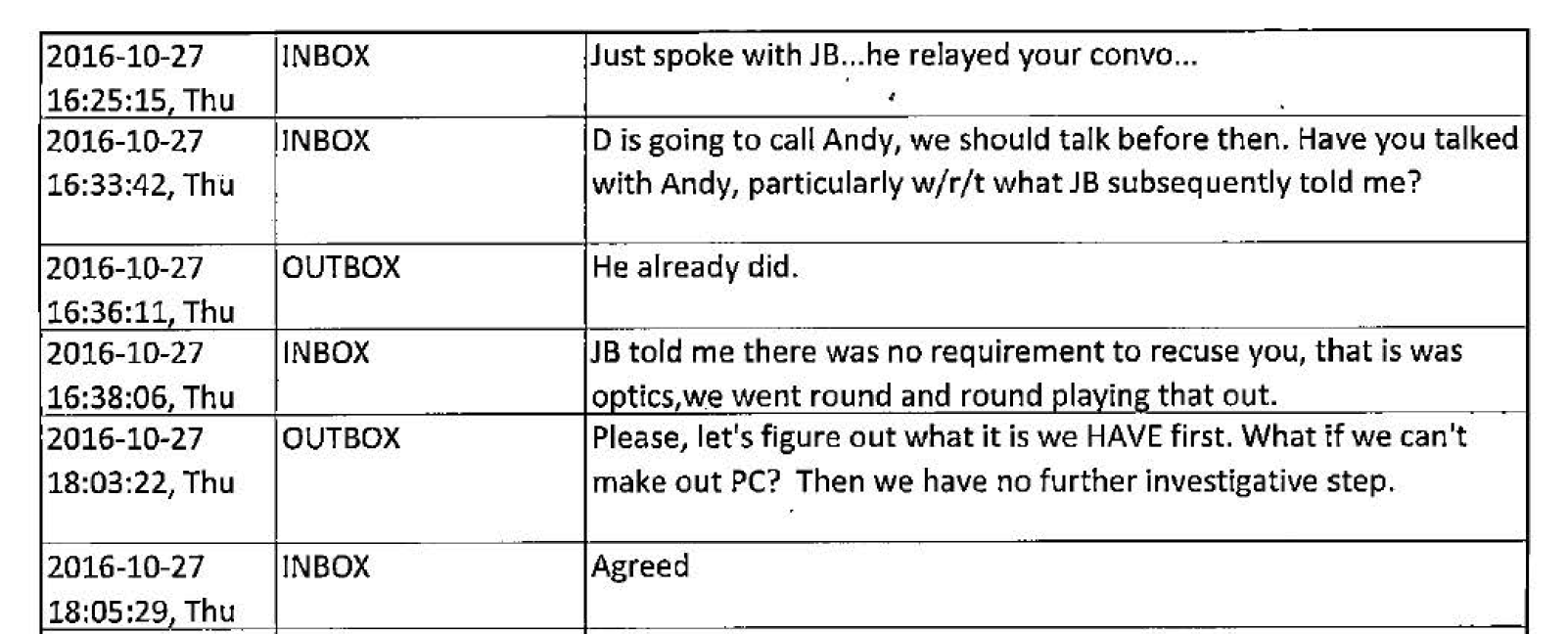

As Sztrok reports, Jim Baker made the decision to recuse Lisa Page, on the basis of “optics.” Apparently, having the lawyer assigned to Andrew McCabe continue to participate would look bad, after the uproar over Devlin Barrett’s WSJ hatchet job. This was a grave error. The Midyear team appears to have been pretty balanced up to this point, with some Clinton supporters and some critics. With McCabe and Page out of the picture, the balance tilted severely toward Clinton’s opponents, the ones who, like Comey, assumed she had committed a crime. None of the remaining members of the team had the ability to right the ship when it tilted too strongly in the anti-Clinton direction.

Page’s desperate message to Sztrok, who was still on the Midyear team, is right on point: “Please let’s figure out what it is we HAVE first. What if we can’t make out PC [probably cause]? Then we have no further investigative step.” Yes, probable cause. That is the correct question that Comey and the rest of the Midyear team seem to have forgotten when they decided quickly to forge ahead. You cannot get a search warrant without demonstrating probable cause.

Here’s a decent definition of probable cause “Probable cause is a requirement found in the Fourth Amendment that must usually be met before police make an arrest, conduct a search, or receive a warrant. Courts usually find probable cause when there is a reasonable basis for believing that a crime may have been committed (for an arrest) or when evidence of the crime is present in the place to be searched (for a search).”

You might respond by saying, well, they did eventually obtain a search warrant, so there must have been probable cause. That is true, but it was on Sunday October 30, after all of the publicity. At that point the Magistrate probably felt he had little choice but to let it play out. But more importantly, take a close look at the search warrant application, which I helped get released from the Southern District of New York in December 2016. Do you see anything about the AT&T Blackberry domain or the time frame that Comey says were the reason for continuing the search? There’s nothing. Nothing about what Comey says was the real reason for the search.

It is possible that the information is redacted, but why? I have recently filed suit against the FBI to remove the redactions. We need to review all of this search warrant. But it looks to me as if the FBI did not disclose to the Magistrate the true purpose of the search. Had they done so, they might not have obtained the warrant, or it might have been limited. The warrant was obtained on pretextual grounds, as if there was an immediate need to secure duplicates of a few classified emails on a hard drive that was already in the possession of the FBI.

It is possible that the information is redacted, but why? I have recently filed suit against the FBI to remove the redactions. We need to review all of this search warrant. But it looks to me as if the FBI did not disclose to the Magistrate the true purpose of the search. Had they done so, they might not have obtained the warrant, or it might have been limited. The warrant was obtained on pretextual grounds, as if there was an immediate need to secure duplicates of a few classified emails on a hard drive that was already in the possession of the FBI.

Comey says he checked on the email review every day. Apparently he was surprised that the FBI’s Operational Technology Division was able to figure out a way to eliminate all of the duplicate emails they had already reviewed. That’s what I would have expected, but perhaps I know a bit more about computers than Comey does. In any case, even though there were no emails from the time-frame that they wanted to search, the team still spent the next week reading through other emails, trying to find something that didn’t exist. By Sunday morning, November 6, they had given up. But by then the damage was done. On that day, Trump’s chances of winning had gone up to better than one in three.