Last weekend I had the opportunity to work at the Geni.com table at the Southern California Genealogy Society Jamboree in Burbank, California. I’ve attended about ten of these types of conferences, and it’s fun to work at an exhibit table and meet many of the attendees. Of course, the main problem with working the exhibit tables is that you don’t get to see the lectures, but some of them are usually available online after the conference. Still, you get to see lots of people in the exhibit area, and most of the speakers also spend time in the exhibit room. What I’ve noticed is that, by and large, you see the same speakers and exhibitors at genealogy conferences. It’s almost like a club. And so by now I recognize lots of people when I attend a conference.

Pretty much everybody who attends a genealogy conference is a bit crazy. After all, what normal person would forgo spending time outside or with family, and instead hang out in a hotel convention hall with a bunch of other crazy genealogists? But the attendees tend to divide pretty evenly into two groups: those who know they are crazy, and those who don’t. (Which group I am in I’ll leave up to you to decide.)

My friend Ron Arons, a professional genealogist who helps find records of criminals, clearly knows that he’s a bit crazy.

The speakers at genealogy conferences tend to be professional genealogists, while many of the organizers and attendees are non-professional members of genealogical societies. I am not a professional genealogist, and have never been certified by the Board for Certification of Genealogists, which just this year received official registration of “Certified Genealogist®” with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. I am also not very active in my local genealogical society (although I did just give a speech on Privacy Issues with Online Family Trees to the Jewish Genealogy Society of Los Angeles, similar to the one I gave at the IAJGS conference in Jerusalem last summer). But anyone who knows my work will recognize that I do as much genealogy, or more, than just about anyone. I’m lucky to have the time to do that. So, I am a hobbyist or “amateur” in the sense that I never ask for money when I help people, but I’m also by now something of an expert in my particularly field (namely Jewish genealogy, especially in Austria-Hungary). And this gives me a peculiar perspective when I attend genealogy conferences.

One of the funny things about professional genealogists is that they love to append lots of silly acronyms to their names. So, in the conference program you’ll see people like Thomas Wright Jones, PHD, CG, CGL, FASG, FNGS, FUGA. (I guess he hasn’t read this blog “No One is Impressed.”) For some reason, genealogists love these acronyms, which generally refer to some certification course they took, or some professional society they joined or were honored by.

But the truth is that genealogical expertise is local, meaning that it isn’t something you can take a general course on and apply to a particular genealogical problem. I could hire every professional genealogist in America, from every acronymed professional association, and still not find an answer to a genealogical question I have, unless one of them happens to be an expert in the particular area where I am researching.

I have hired a number of professional genealogists over the years. The first was Eugen Stein (and his wife Iva) who were the best (maybe only) Jewish genealogists in Prague during the Communist era, a time when having any interest in Jewish things was dangerous. The Steins knew where to access the records I needed, and they gave me a wealth of information I could not at that time find on my own. I also once hired the Austrian genealogist Felix Gundacker, who runs the website Genteam.at, in order to find out something about my one non-Jewish gg-grandmother Karoline Inquart who had abandoned her Jewish husband Theodor Hoffmann and kids and ran off with an Italian count named Lovatelli. Felix found an early civil, non-religious marriage record from 1875. Karoline, who was just 15 years old when she married, and turned out to be the step-daughter of her 25-year-old husband Theodor’s first cousin, was listed as “without religion.” There is no way I would have found that record without the professional help of Felix, who knew that civil marriages began in Austria in 1870, and knew how to find them. Since then I have employed other professionals, including Julius Müller in Prague, now by far the best professional in that region dealing with Jewish records, and author of the Toledot webpage. Julius went to regional Moravian archives to find information about some of my families, locating records that will probably never be available online. In Vienna, my friend Wolf-Erich Eckstein is the go-to person for finding graves in the overgrown Jewish cemeteries, as this video from our 2014 visit to the Währinger Friedhof demonstrates. For Hungarian research, I once got help from Maureen Jellins, who was familiar with the MACSE website and the Hungarian language. Recently, I’ve had luck with Nadia Lipes of Jewua.info, who took my wife’s Ukrainian Jewish genealogy back a few more generations, using local resources. And lately Andres Rodenstein of Vital Records helped me track down family members who fled from Austria to Argentina and Uruguay during World War II.

So, I’m a big fan of hiring local professional genealogists who can help find things that I otherwise would never find. But these folks are nothing like the multi-acronymed professionals who travel around giving lectures at genealogy conferences. Maybe that’s a bit harsh. The conference professionals are all probably decent genealogists, but like everyone, they’re limited to what they know. Genealogy is local.

As an example, you could look at a very public genealogist, Megan Smolenyak, who writes a lot on Huffington Post. Last year she wrote about how she found an error in all of the online trees for Hillary Clinton. Smolenyak was right. Everyone else had gotten the parents of Hillary’s paternal grandmother Hannah Jones from Scranton, Pennsylvania all wrong. Smolenyak may be a terrific genealogist, but the reason she found the mistake was that she had roots herself in the neighboring city of Wilkes-Barre. She found a notice in a local Scranton paper that pointed to a marriage across the border in Binghamton, NY, which Smolenyak recognized as a place where eloping couples often went to get married. This provided the key for figuring out which Hannah Jones in Scranton was Hillary’s grandmother. As I said, genealogy is local, and Smolenyak was an expert in that area because that’s where her family was from.

It’s often not easy to judge whether someone is an expert in the area that you are researching. Strangely, most professional genealogists do not have their own trees publicly available. I am continually surprised to find that many professional genealogists aren’t contributing to the World Family Tree on Geni.com. (See for example, this project I set up for the speakers at the National Genealogical Society 2016 Family History Conference.) Most of them have standalone profiles (meaning no parents, etc.). Probably they signed on one time, took a quick look around, didn’t find what they were looking for and moved on. To me, this indicates a lack of interest in their own roots. After all, I know many people (like me) who keep trees on all of the various platforms, just to increase the likelihood someone will find them. That is what good genealogists do.

Some people speculate that professional genealogists don’t add their trees to the World Family Tree because they don’t want to give anything away for free. I think it has more to do with the training they receive at the various certification societies, with a faux-lawyerly emphasis on “client confidentiality” (as if anyone really needs to keep a family tree secret). Whatever the reason, you’ll be hard-pressed to find well-developed public trees of the majority of professional genealogists. That’s a real shame, I think — a loss to them, as they won’t find information that might be out there (do they think they know it all?); and a loss to us, because if we could harness their energy, the World Family Tree would be growing even faster than the current 9 million profiles per year. It also reflects a lack of scientific seriousness about genealogy. If you don’t publish your work and allow it to be reviewed (as all scientists and academics do, for example) you really cannot advance the field or find out if you made a mistake. A field in which no one publishes their work so that it can be verified is not rigorous enough to be taken seriously.

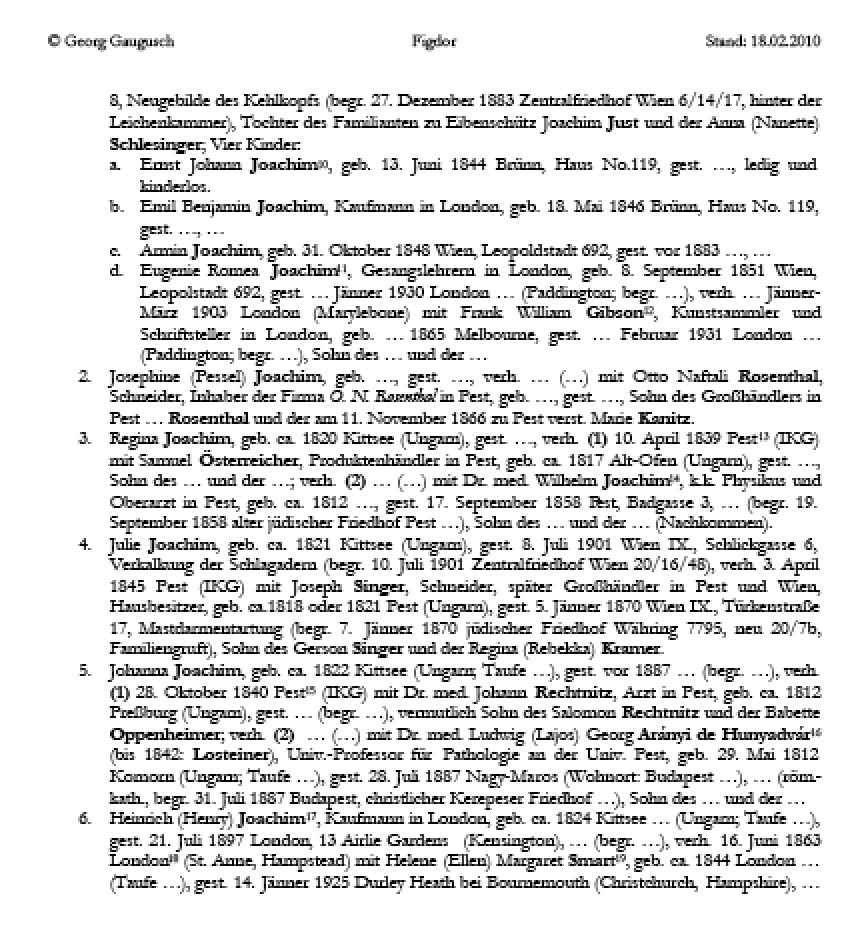

A brief excerpt from Georg Gaugusch’s work on the Figdor/Joachim family, from the 1650-page Wer einmal war (A-K).

Professional genealogists maybe don’t realize it, but they could learn a lot from the non-professionals in their midst. Many of the almost 200 volunteer curators on Geni are extremely knowledgeable in their fields, and as good or better than any professional (and they’ll help you for free). In fact, the best genealogist I know is not a professional (and also doesn’t work on Geni). Georg Gaugusch is a 42-year-old Austrian who owns the men’s haberdashery Jungmann & Neffe around the corner from the Hotel Sacher in Vienna. Inspired by the old customer lists he found in the shop, he has become the leading expert on the Jewish haute bourgeoisie of Vienna. The first volume of his tome Wer einmal war (A-K), published in in 2011, is 1650 pages of the most meticulous, expert genealogy I have ever seen, culled from numerous difficult to find, and read, primary sources. The second volume (L-R) is due out this Fall. We have a Geni project where you can see for yourself the families Georg has investigated, although his book contains many more details than what has been entered so far on Geni. If there are any professional genealogists who can match what Georg has done, I’d be happy to learn their names and see their work.

But as nutty as some of the professional genealogists are, they aren’t the craziest ones at the conference. That title goes to the ones who come up to the Geni booth and demand to see if someone has “stolen” their family tree and put it on Geni. No amount of explanation can temper their ire. The mere suggestion that they might not have the right to tell other people what they can and cannot put on a family tree sends them into a fit of fury. No, their family trees are highly valuable trade secrets that must be kept out of the public domain. It’s all on their hard drive, safe from any intruders. And of course, their work is always 100% correct, although no one is ever allowed to check it to make sure. They cannot be associated with the work of others who certainly don’t meet their high standards. Indeed, their work must be protected from the masses who are all just chomping at the bit to alter their trees and intentionally insert mistakes into their otherwise error-free data. They’ve been taught that public, collaborative family trees are dangerous, and no matter what privacy protections a company might offer, they aren’t enough to protect their family members from the marauding hordes that are just waiting to peek at their family trees to torment them and steal their identities.

Despite all this silliness, I have a great time when I attend genealogy conferences. I’m always looking to learn new things and meet new people. At this weekend’s conference, I helped dozens of people develop their trees on Geni. There’s nothing better than having a person start from scratch and within a few minutes showing how you are related or connected to him or her on the World Family Tree. That’s something that is only possible on Geni, which is why it’s the best platform for tree-building these days. If your professional genealogist is really a pro, she’ll tell you that also and show you her tree.