Pam and I flew to Berlin for the premiere of the film “Woman in Gold” at the Berlinale, the annual film festival in Berlin, Germany. It is an emotional return for me to the city where I lived for six months in 1987, on a Junior year semester abroad, studying math and German at the Freie Universität Berlin. At that time the Berlin Wall still divided the city. Living in West Berlin was like living on an island, free and yet somehow trapped. The city has changed immensely in the 28 years since that time. But coming back has reawakened the old feelings I had as a young 20-year-old, returning to a city with great historical significance, for my family and for the rest of the world.

Back in 1987, I stayed in a tiny room (actually a former kitchen) in an apartment. This time we’re in the fancy Hotel Adlon Kempinski. The view outside our room (if you look to the left) is the amazing Brandenburg Gate.

The first time I was here, you couldn’t even get close to the Brandenburg Gate, since it was surrounded on both sides by the Wall and armed guards. Here’s a picture with my Berlin friend Sebastian Jacobs (next to two random girls and a guy we can’t even remember).

Just hours after arriving, Pam and I were invited to the Berlinale Dining Club for a dinner with other folks from “Woman in Gold.” On the way there, we ran into Helen Mirren at the elevator. She was super nice, just as she was when I met her in July in Vienna. She didn’t go to the dinner, but director Simon Curtis was there and sat next to Pam. I was very excited to meet some of the German actors from the film, especially Justus von Dohnanyi. His father, the conductor Christoph von Dohnanyi is a wonderful interpreter of the music of my grandfather Arnold Schoenberg. When I was at Princeton, I met him once in New York, after a performance of Erwartung. Christoph’s father Hans and his mother’s brother Dietrich Bonhoeffer, were important members of the anti-Nazi resistance, who were executed just before the war ended. Anyway, Justus is a terrifically nice guy and his performance in the film was probably my favorite, because he plays the Austrian attorney who opposed me in the Klimt case in just the way I experienced him. Pam took a nice photo of the two of us that I quickly uploaded to Facebook for my friends to see.

On Monday, I went to the Weinstein Co. offices to pick up our tickets for the premiere. On the way, I walked through Peter Eisenman’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. It feels like a maze where you cannot see who is around every corner. Most times you see no one else. But as you walk through and look to the side, you see lots of other people walking through, or taking photos. It obviously works well as an attraction, and perhaps some people do think about the intended meaning as they are meandering through it. The concrete blocks do feel like giant tombstones, as if you are shrinking as you walk deeper into the field of stones. At the Weinstein offices in the Berlin Hyatt, I met a few of the publicity staff who had been sending me e-mails about the arrangements for the past few months. Simon Curtis, Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds were giving press interviews at the hotel, but I only saw Simon there when I checked in on him. Pam and I went out and visited the street where I lived back in 1987. I couldn’t remember exactly which concrete apartment building was mine, but the church at the end of the street and restaurant were familiar. Here’s what Schmiljanstrasse looks like today.

Back at the hotel I ran into Anne Webber of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe. Anne is an old friend and colleague. She really knows her stuff, and has managed to help recover hundreds of artworks over the years. The Weinstein Co. had invited her to attend the press briefing as an expert. Afterwards I saw Simon, who was waiting for my old friend Matt Weiner, the Mad Men creator, who was serving on the jury at the festival. We caught up for a bit, and it was fun to reminisce about our days as editors of the school newspaper way back when. We’ve both come a long way.

Pam and I got all dressed up. My friend Nick Meyer had suggested I wear a tux, and I figured I might as well go through with it, even though everyone else was probably going to be less formal. The film folks had a big press event, but I was not specially invited, so I figured I would have dinner with Pam and our guests before the screening that night. My old friend Sebastian and his wife Franziska came, as well as my cousin Gabriel Loewenheim, an opera singer from Haifa who now lives in Berlin, and a last minute addition our friend’s daughter Ariella Kattler-Kupetz, a student who arrived just a week ago on a semester abroad. Sebastian is a judge and told us about his trial that day, involving a 500-lb man who had to be moved by the authorities out of his apartment just to attend the trial, which had to be in a special location because they could not get him up to the regular courtroom.

We made our way to the Friedrichstadt Palast for the premiere. We walked the red carpet, but even wearing a tux, not a single person figured out who I was. We had Ariella take our own photo. We got into our seats and waited for the show to start. The theater is huge, maybe 1,200 seats. Tim Schwarz and his wife Antoinette were in the row in front of us. Tim had produced the documentary on the Klimt case “Stealing Klimt,” and was part of the reason the film got made since he was the one who told the story to Simon Curtis. Simon came on stage with Helen Mirren, Ryan Reynolds and Daniel Brühl to introduce the film. I was genuinely surprised when Helen called me out from the stage and asked me to stand. That was really nice.

We got into our seats and waited for the show to start. The theater is huge, maybe 1,200 seats. Tim Schwarz and his wife Antoinette were in the row in front of us. Tim had produced the documentary on the Klimt case “Stealing Klimt,” and was part of the reason the film got made since he was the one who told the story to Simon Curtis. Simon came on stage with Helen Mirren, Ryan Reynolds and Daniel Brühl to introduce the film. I was genuinely surprised when Helen called me out from the stage and asked me to stand. That was really nice.

Pam and I had seen a draft of the film in October, but not the final cut and we had not heard the music scored by Hans Zimmer for the film. Even knowing the film already, it was a different experience seeing it in a large theater on a giant screen. I felt I was paying attention very closely, more than the last time. Occasionally I saw a small mistake (they’re driving the wrong way on the freeway) and made mental note, but at several places I really became extremely emotional. There is one line that I had given the writer Alexi Kaye Campbell, something my grandmother had said when she took us back to Austria when I was a teenager. Gamma, as we called her, was nearly always happy, really never sad, morose, angry or mean. But as we rode the train into Austria she became misty-eyed and said “I’ll never forgive them for not letting us live here.” She loved her Austrian homeland. She was 33 when the Nazis came and she was forced to flee, on the day after Kristallnacht. To her dying day she thought of herself as an Austrian, probably more so than her younger friend Maria, who was just 22 years old when she left. Alexi gave this line to Helen Mirren’s Maria in the film, and when she said it, I almost lost it. Thinking of my grandmother has always done that to me. There is another scene in the movie, where Ryan Reynolds is at the Holocaust monument in Vienna and gets that emotional hit. That was something that really happened. I was there at the unveiling of the monument, thinking about my grandmother and my great-grandfather Siegmund Zeisl who was murdered at Treblinka and just started crying. That’s when I met my friend Thomas Lachs, who spotted me and realized I had a real connection and wasn’t just there for the ceremony. Anyway, this happens to me, and it happened to me again and again during the film, which is I think a real testament to the emotional power of the performances, and to the emotions they were awakening in me. At several places I reached for Pam’s hand and held it tight. The ending of the film, where young Maria, played wonderfully by Tatiana Maslany, says a final goodbye to her parents just shattered me. You just cannot be unaffected by Allan Corduner (Maria’s father Gustav)’s farewell speech. It may be schmaltzy, but it works as a film. At least it works on me. An almost uncontrollable wave of emotion hit me at the end.

I suppose to some viewers it might seem maudlin to evoke these type of emotions in a film. But the audience seemed genuinely affected. The applause was thunderous and lasted a long time. Pam and I were brought back stage, and I hugged Simon and Alexi and thanked them profusely. Telling the story, telling Maria’s story and the story of her family, of our families, was the prime mover for me during the entire ordeal. Now it was a huge film, and so many people would see it.

I seemed to be the happiest person backstage. I greeted executive producer Harvey Weinstein for the first time and he was a bit cool. I learned later that the first reviews had just come in, and were not as good as they had hoped. (More on that later.) At that time, I had only seen a very positive Austrian review, and was untroubled by any concerns for the reception of the film. I met Daniel Brühl, who was running the jury for the festival, and he told me that the applause for this film was greater than for any other film at the festival.

At the post-screening party, we took a nice photo with Matt Weiner and his wife Linda Brettler (whose younger sister Sandra was in my elementary school class). This will be a good one for the Harvard-Westlake Alumni magazine. We had fun at the party. At the end I sat with Harvey Weinstein and really introduced myself. He was busy on his iPad, doing whatever it is that he does to make his movies succeed. I only figured out later he was probably dealing with the reviews that had just come out. I told him not to worry. This story is charmed, and whatever touches it turns to gold.

We had fun at the party. At the end I sat with Harvey Weinstein and really introduced myself. He was busy on his iPad, doing whatever it is that he does to make his movies succeed. I only figured out later he was probably dealing with the reviews that had just come out. I told him not to worry. This story is charmed, and whatever touches it turns to gold.

When Pam and I got home, I looked for the reviews and saw some of the really not nice things published in the Guardian, Variety, Hollywood Reporter and IndieWire, which were in stark contrast to the much more positive reviews in Screen (“a classy real-life story . . . thoroughly enjoyable”), Huffington Post (“stunning”), HeyUGuys (“a bonafide story of the underdog”), The Art Newspaper (“Helen Mirren shines as Maria Altmann”), FlickFeast and London Evening Standard (“heartwarming story of belated justice”), the German press Der Spiegel, Jüdische Allgemeine, FilmStarts, the Austrian newspapers Kurier, Salzburger Nachrichten and Die Presse, and even the Italian press Movieplayer.it and Sentieri Selvaggi. I think it is very interesting that the German and Austrian critics were positive about the film. It is not easy to make a Hollywood film about the Nazis that Germans will like, and this movie has a number of lengthy flashbacks to those times, with scenes of jubilant Austrians greeting Hitler’s arrival in Vienna, and various degradations imposed on Austria’s Jews, not to mention Maria and Fritz’s harrowing escape, which was very dramatically portrayed, but in some ways even less scary than what actually happened. (The film doesn’t mention that Fritz spent weeks in Dachau before being ransomed out by his older brother, nor does it show the escape over the border to Holland, aided by a priest who was later murdered by the Nazis).

It seems likely that the jaded trade reviewers assumed that everything they saw had been “Weinsteined” to make it more dramatic. Certainly this was the case in some scenes. (Pam’s water did not break when I was packing to go to argue in the Supreme Court, but she did call me from the hospital when I was in Washington just two days before my argument, because she went into premature labor at 29 weeks.) But the reviewer’s failure to appreciate how much of the film was true to life underscores the real need for a film like this to succeed. For them the emotional core of the film felt “manipulated,” even one-sided. The reviewer for Variety Peter Debruge even complained that so many Austrians were portrayed as bad guys, and that viewers were not given an opportunity “to question Maria Altmann’s case.” The Guardian‘s Ryan Gilbey was similarly offended by the portrayal of our Austrian opponents: “sinisterly obstructive officials who only just stop short of clicking their heels.” If he only knew . . .

As far as the portrayal of Austrians is concerned, I think the positive reaction of the German and Austrian press leaves little doubt that the portrayal is accurate and plenty nuanced. (“Not least for our domestic education and a better understanding of the facts is ‘Woman in Gold’ therefore sure to become popular.”) The character of Hubertus Czernin (played by Daniel Brühl), for example, is wonderful, and I liked very much how Alexi put some of my own words in Ryan’s mouth for his final speech “There are two Austrias. . . ” But one of the reviewer’s own readers already had the best response: “This strange review seems to be a plea for more ‘balance’ in portraying Nazis.”

I suppose it is always going to be difficult, after we have won, to show how hopeless the case seemed all along. It may seem “Weinsteined,” and easy to dismiss or forget, when the reporter approaches Ryan Reynolds to assure him that he would lose the Supreme Court case, but then the reviewer didn’t have to read this headline “Court Likely Will Reverse Art Case” in our legal newspaper after returning home from Washington. If the reviewer thought that watching us win was dull, he should be forced to suffer through the movie he apparently wanted to see — eight years of stonewalling with infuriating, procedural, counterfactual arguments and roadblocks. It is almost as if the reviewer wanted the filmmakers to have invented better arguments on the other side, just to make the film more interesting. But on this point, the story is really the opposite of Stanley Kramer’s great film Judgment at Nuremberg, which perhaps explains why it wouldn’t work to make the Austrian position more attractive than it was. As the reactions of the reviewers demonstrate, there are still plenty of folks who have a knee-jerk stance against restitution of stolen Jewish property. Some of them are unabashed neo-Nazis.

I guess if you’ve read this far, you’ll be inclined to trust me when I say that the negative reviewers seem to have some sort of axe to grind that has really very little do with the film that was made. The Hollywood Reporter critic David Rooney liked Helen Mirren’s portrayal of Maria, but thought Ryan Reynolds was too much of a “goy.” Well, ok (no less that the stars of Barry Levinson’s Avalon), but at least one other reviewer, Mark Adams, found it an “engagingly subtle performance . . a nice change of pace and tone for the actor.” Rooney didn’t like Phipps & Zimmer’s score and wished they had used Schoenberg. Yeah. But seriously, I realized early on that this story was not going to be told as an art house movie. A nerdy grandson of Austrian exiles is not a protagonist that most people want to watch for two hours. Sure, I’d love to score the whole movie with the Begleitungsmusik. But who else is going to come watch with me? As I recently told the LA Times, I knew that I had to give up control and allow a certain amount of license if this story was ever going to be made into a film. Even my grandfather was once willing to sell out to Hollywood. So, yes, this is not a small art-house flick with quirky directing and an experimental screenplay. But really, is that so bad? This is a story that countless people have told me they find inspirational. If that isn’t a good enough justification for a Hollywood movie, what is?

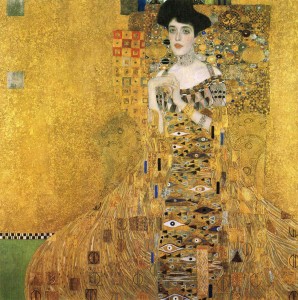

Apparently Variety‘s Peter Debruge just isn’t that comfortable with the idea of people owning personal property. I thought the communist-capitalist debate had been sort of put to rest with the fall of the Berlin Wall, but I guess not. His review claims: “there’s a monumental issue at stake here that the film scarcely acknowledges: Does (or should) anyone really own art? At a moment when the music and movie industries have all but lost control of their own product and the public feels more entitled than ever to access such media for free, what does it mean for the world’s most valuable paintings to remain in private hands?” IndieWire’s Jessica Kiang seems to agree with this bizarre sentiment about the “thorny issue of art ownership,” and thinks that Austria’s “right to any sense of cultural identity” gets short shrift in the film. Seriously? Let’s leave aside for the moment the fact that the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer was purchased by the Neue Galerie in New York and is on permanent public display, and also that Klimt’s copyright has expired and so the image can be plastered at will on college dorm rooms and used for fridge magnets, scarves and coffee mugs sold throughout the world. Is the “monumental issue” really whether people get to look at a pretty painting, or is it whether we are okay with the idea that private property confiscated by the Nazis was never returned? I guess I (and the filmmakers) are guilty of mistakenly believing it was the latter.

Some of the reviewers didn’t like Martin Phipps and Hans Zimmer’s score, calling it “so much heavy-handed strings-and-pianos business.” Personally I found their music unobtrusive and harmless, and maybe less Korngold-esque than I would have preferred. But none of the reviewers even bothered to mention the Mozart, Schubert and Schoenberg used in the film either. The short section from Verklaerte Nacht was nice, even if the concluding chord tacked on at the end was for me a bit jarring. Maria’s husband Fritz, who always wanted to be an opera singer, would have loved his portrayal by the excruciatingly good-looking Max Irons, and Maria, who always loved to quote operas (in the most unpretentious way), would have smiled at the Mozart aria sung by Fritz at their wedding.

None of the reviewers seemed to understand how difficult it was to make a film like this. How many films can you name that successfully cover 100 years of history? (Istvan Szabo’s Sunshine is the only one I can think of, and it was problematic.) Successful courtroom dramas are pretty much all completely invented or include scenes that are mostly impossible. (I loved A Few Good Men, but you don’t really get confessions like that in real life. And what lawyer didn’t laugh at the “climactic” summary judgment denial in Erin Brockovich?) It’s not so simple to make a legal drama that is accurate. (This one has me on the wrong side of the room in the Supreme Court, and of course my partner Don and not Maria was sitting next to me — for all those making a nitpicking list.) Let’s remember that this 100-minute film had to cover the period from 1906-2006 spanning two continents, and include both Nazi times and a lawsuit going to the US Supreme Court. Is it really any wonder that Katie Holmes’s part as my wife Pam is a bit perfunctory (but still cute)? Oh, and remember it required filming in two languages. Sure, I liked how Quentin Tarantino had his Nazi Christoph Waltz speak English, so that others couldn’t understand him, during his interrogation of a French farmer in Inglorious Basterds, but does anyone think that would ever have happened? It’s not easy filming a story that takes place in two languages and this film does a really good job with it, or so I thought.

As a final example of the pettiness of the critics, in the Guardian, Ryan Gilbey really takes Alexi to task for one old joke: “‘It would have been a lot better for us all if Hitler had spent his life doing tacky paintings,’ says Mirren’s Maria, taking the stating of the bleeding obvious to a new level.” Well, that’s actually a joke that Maria said, numerous times, and I usually use it when I give my speeches on the Klimt case. I’ve seen it attributed to the artist Oskar Kokoschka. Did Gilbey really think Alexi invented it? But seriously, it’s hard to read a critique like this from a guy who recently wrote, of his somewhat confused past sexuality: “Those women were the only girlfriends I’ve had and the only women I’ve been attracted to. It just so happens that I made both of them pregnant, which has tended not to be the case when I’ve slept with men.” Apparently a joke about “the bleeding obvious” is okay for him, but not for Maria Altmann.

So, I have to apologize to the critics who think that our true story is just too Hollywood to be true. What can I do about it? All I know is the audience seemed to love it. Harvey Weinstein told me that the ratings at their screenings are off the charts. This is one of those films that is just going to have to defy the critics. Maria and I did it for eight years together, and we’ll do it again.