Rabbi Gershon Shaul “YomTov” Lipman Heller (1579-1654) is justly famous for both his rabbinic writings and his life story. An intrigue against him while serving as Chief Rabbi of Prague in 1629 led to his imprisonment in Vienna and a death sentence that was commuted by the Emperor Ferdinand II, resulting in a heavy fine. In his autobiography, Megillat Ebah, Heller thanked Heni [Enoch Weiseles] and Wolf Slawes for helping to pay the fine and secure his release from prison. This article attempts to correct 320 years of confusion about the identity of Wolf Slawes.

Although I was not brought up with knowledge of the great talmudic rabbis, I discovered Heller, who is known by the title of his most famous three-volume commentary on the Mishnah (“Tosafot Yom Tov”), many years ago while searching for the unusual hyphenated surname of my gg-grandmother Karoline Jontof-Hutter from Prague. The first reference I found was from Karl Marx‘s Das Kapital, where he quotes without attribution the words of his cousin, the poet Heinrich Heine, in Disputation, the last poem from Heine’s Romanzero: “If Tosafot Yom Tov is no longer valid, what else can be valid, brawl, brawl!” (“Gilt nicht mehr des Tausves Jontof, was soll gelten, Zeter, Zeter!“). Clearly, in religious circles and even beyond, the word of Rabbi Heller was law.

In Megillat Ebah, Heller commanded his descendants to recall his ordeals, and so his manuscript was copied and passed down in various forms (some Hebrew, some in Judeo-deutsch or Yiddish) through the generations. Joseph Davis’ biography Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller: Portrait of a Seventeenth-Century Rabbi (2005) identified nine different manuscript versions of Heller’s autobiography in libraries around the world. Davis, p. 228, n. 31. The 19th Century saw the publication of several versions of the autobiography. The first publication in Breslau in 1836-37 included a translation into German by Josua Höschel Miro. An 1880 publication in Vilna, under the name of Heller’s son Samuel, containing additional details not found in other versions, was considered by contemporaries to be an embellished forgery. See David Kaufmann, Die Letzte Vertreibung der Juden aus Wien und Niederösterreich, p. 20 n. 2 (1889). Of course, that didn’t stop people from relying on it. In 1929, Guido Kisch published an 80-year-old German translation by his cousin Seligmann Kisch, along with a description of the eight previous publications from 1836 to 1897. Guido Kisch, “Die Megillat Eba in Seligmann Kischs Übersetzung,” Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Juden in der Cechoslovakischen Republik, I. Jahrgang, p. 421 (1929). There is apparently a debate among the scholars as to whether the original version by Rabbi Heller was in Hebrew or Judeo-deutsch/Yiddish, but what is certain is that the original has not survived. See Rachel Greenblatt, To Tell Their Children: Jewish Communal Memory in Early Modern Prague, p. 230 n. 27 (2014).

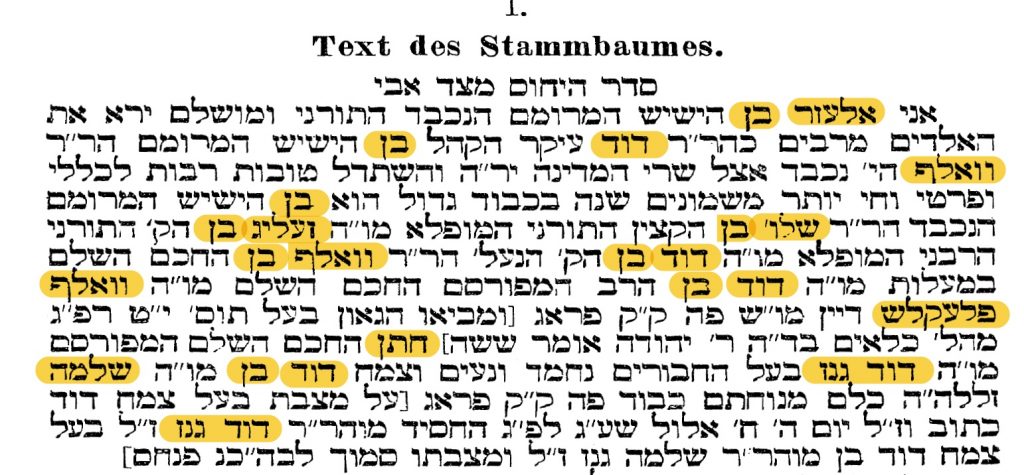

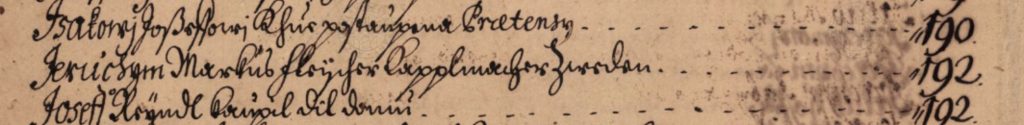

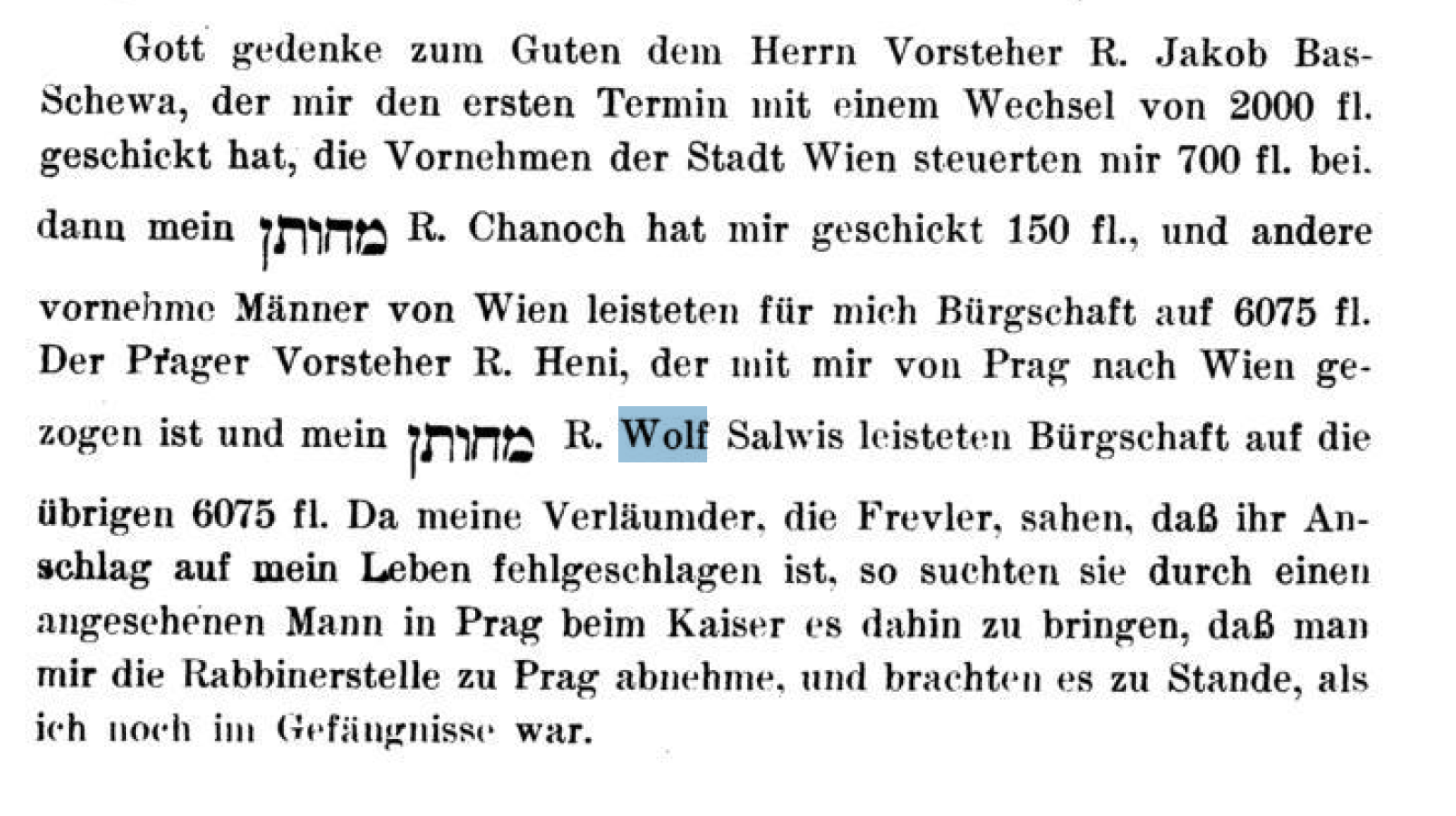

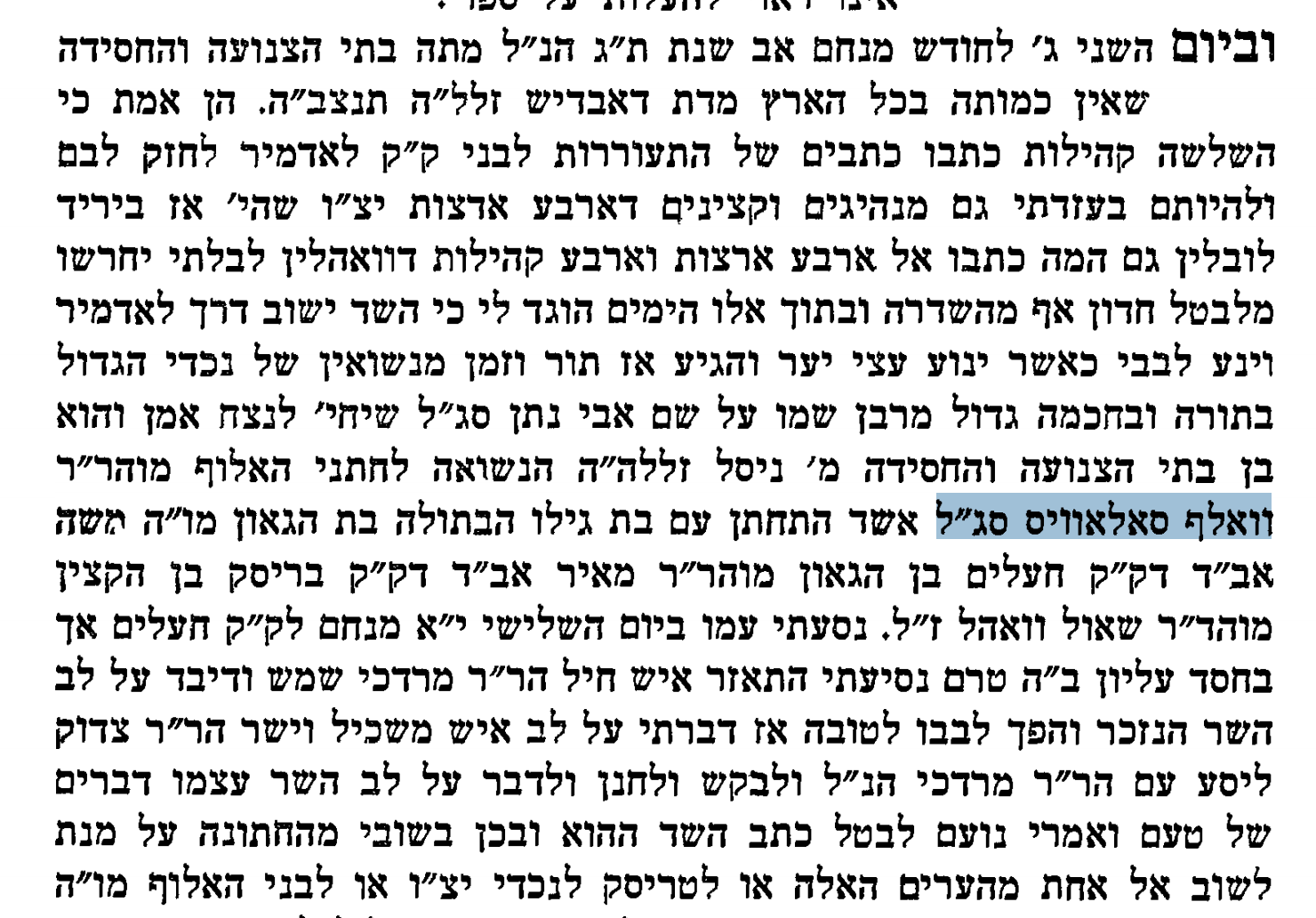

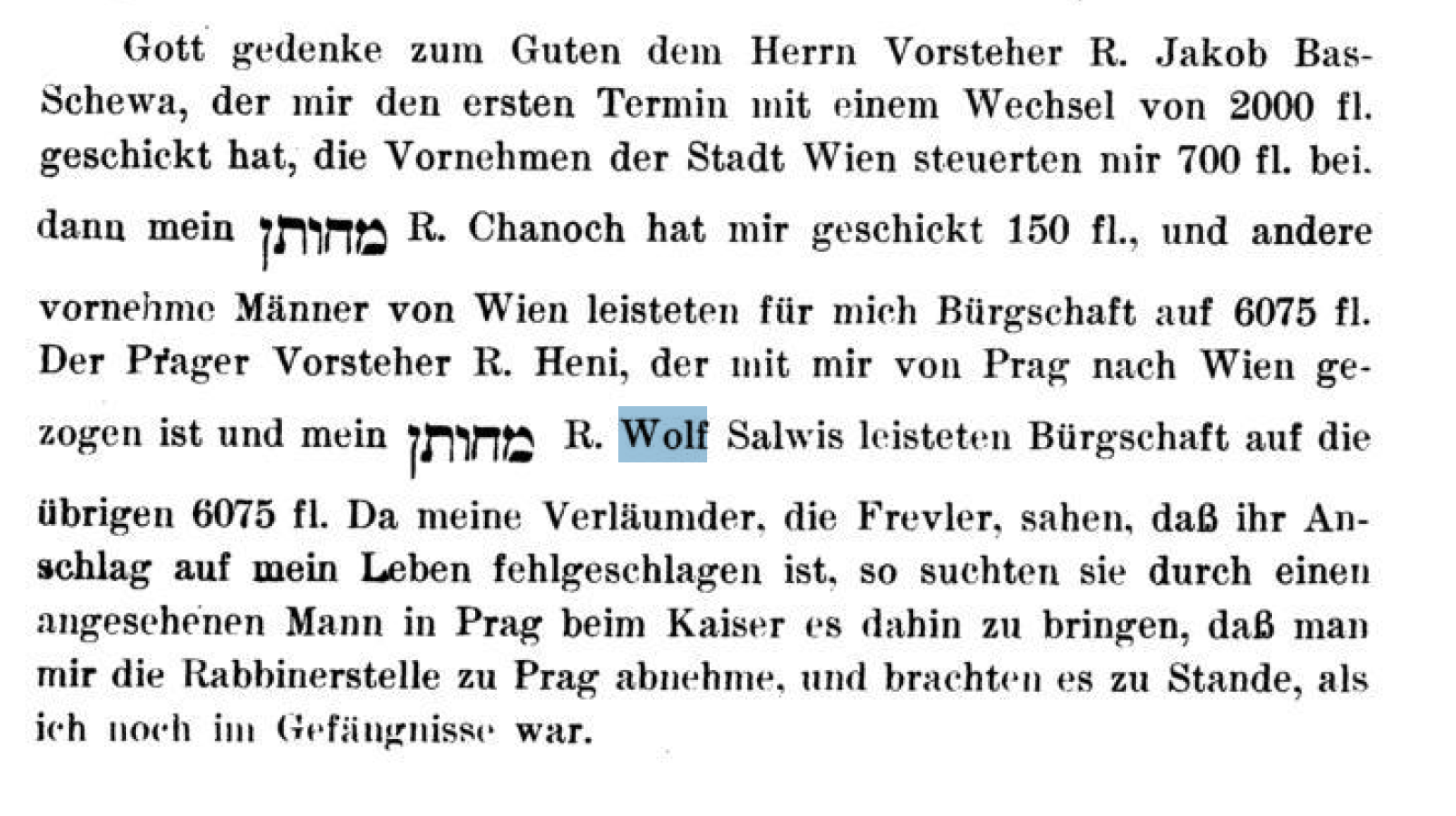

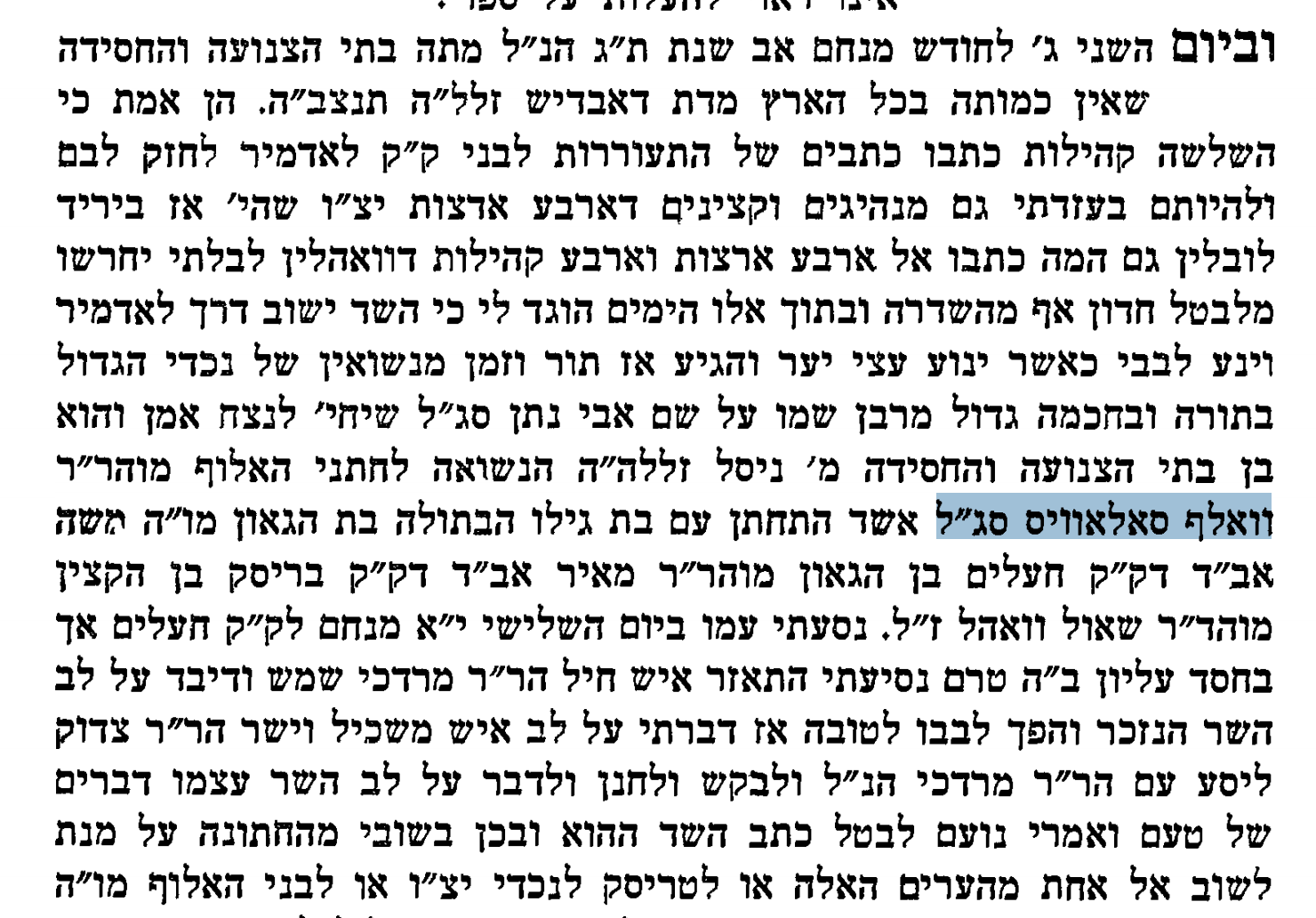

So what do all of these versions of Heller’s autobiography say about Wolf Slawes? The first mention of Wolf Slawes in the autobiography says approximately this: “The Prague councilman R. Heni, who came with me from Prague to Vienna, and [my relative] Wolf Slawes guaranteed the remaining 6,076 florins.” In some versions, Wolf Slawes is referred to later as Heller’s son-in-law, the husband of Heller’s daughter Nissel. In others, Wolf is a machaten, a unique Hebrew term used for an in-law, including the parents of your son-in-law. In the early German translations, Wolf Slawes is referred to as the son-in-law of Heller’s good friend Heni. And in several Hebrew versions, Wolf is called Wolf Slawes SeGal, indicating that he was a Levite.

Guido Kisch, “Die Megillat Eba in Seligmann Kisch’s Übersetzung,” Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Juden in der Tschechoslovakischen Republik, p. 440 (1929).

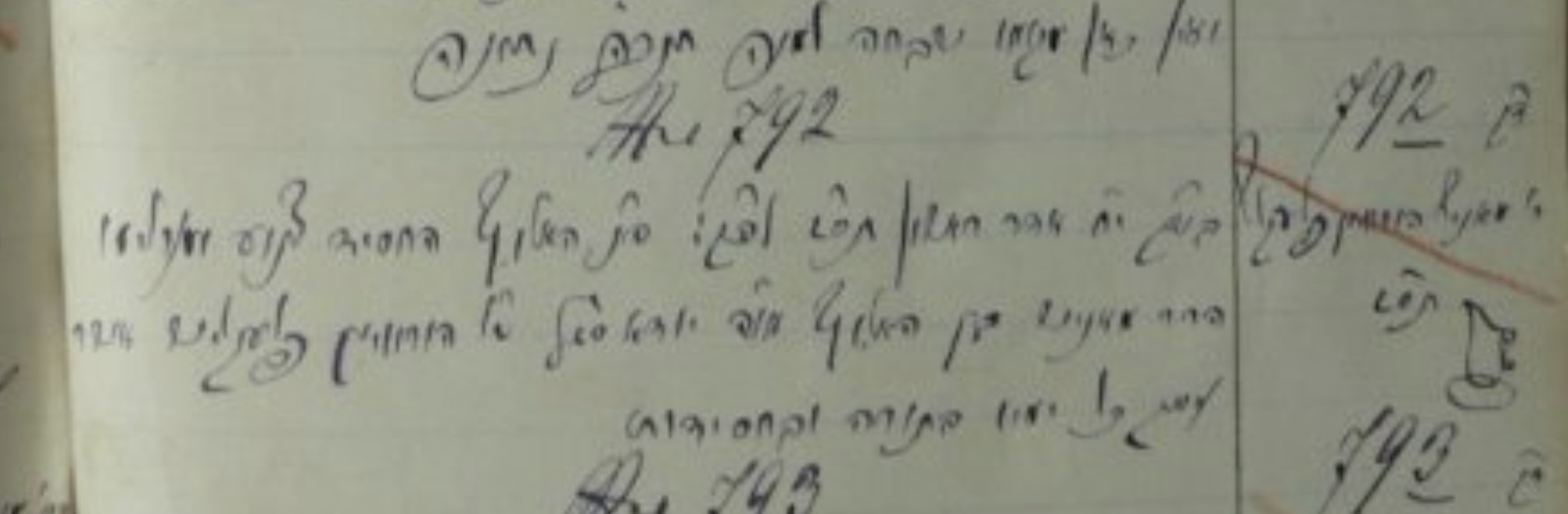

Megillat Ebah, Yom Tov Lipman, date unknown (after 1895). https://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=3840&st=&pgnum=16

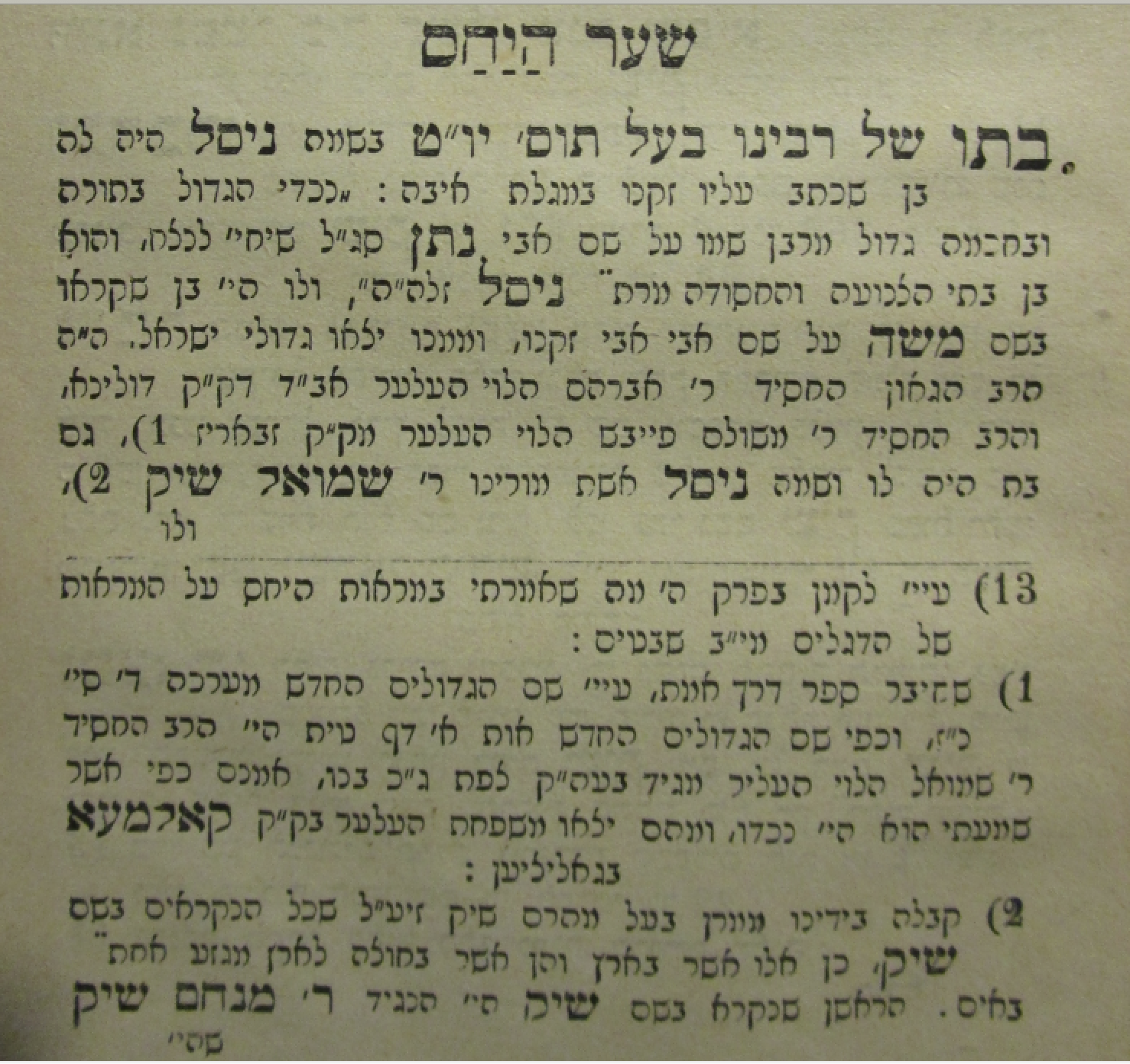

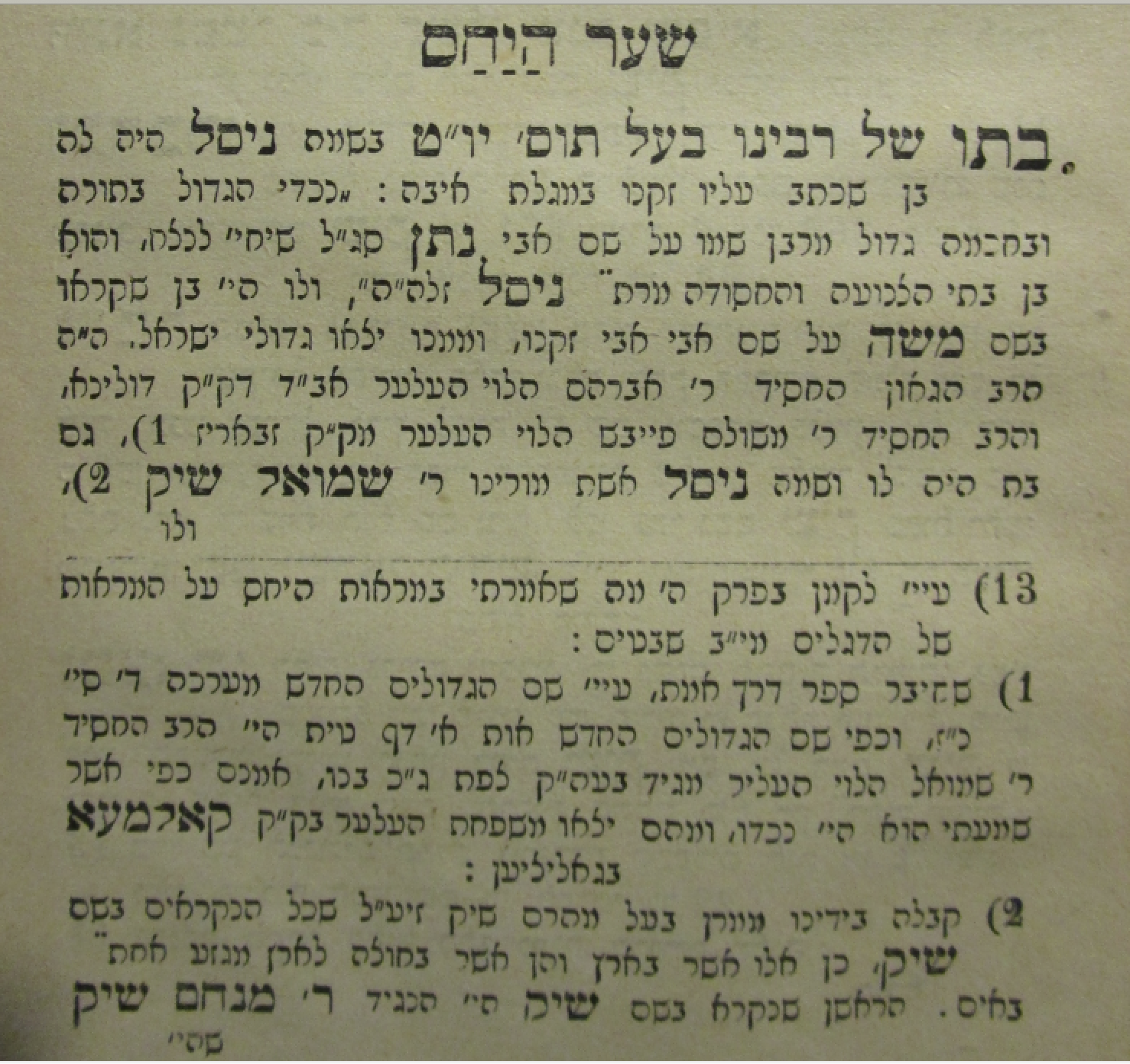

Wolf Slawes’ relation as son-in-law, husband of Rabbi Heller’s daughter Nissel, is the version that most genealogists have adopted, notably in the history of the Schick family compiled by Solomon Zvi Schick’s Mi Moshe Ad Moshe (Kahn and Fried Publishers, Munkacs 1903). This version also appears in all three editions of Neil Rosenstein’s Unbroken Chain (see Third Edition, Vol. I, Chapter Two, Section B, page 40) as well as in The Jacobi Papers, Vol. IV, p. 118, 11.2. In all of these Wolf and his male descendants are Levites.

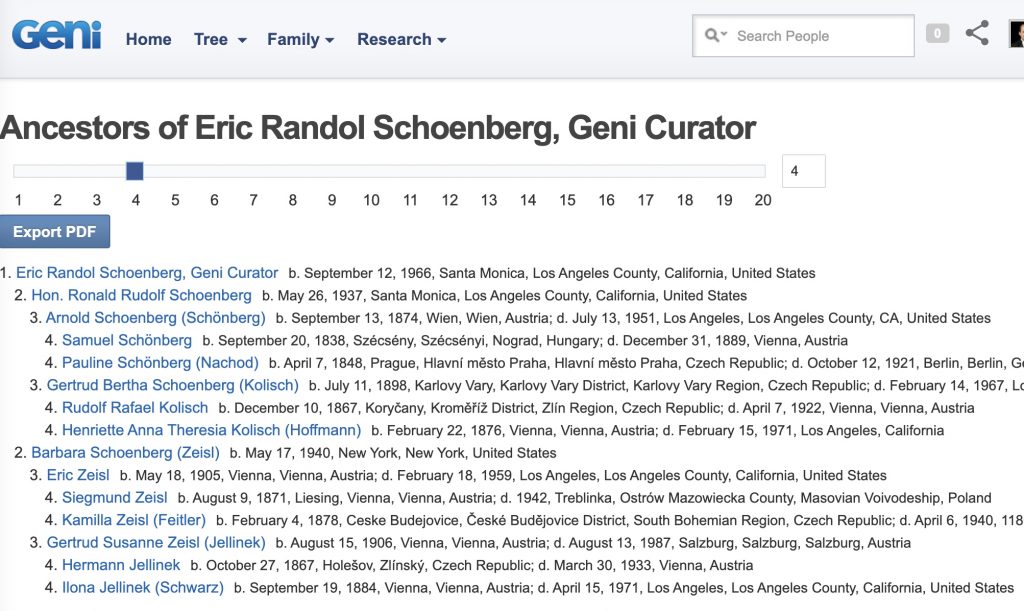

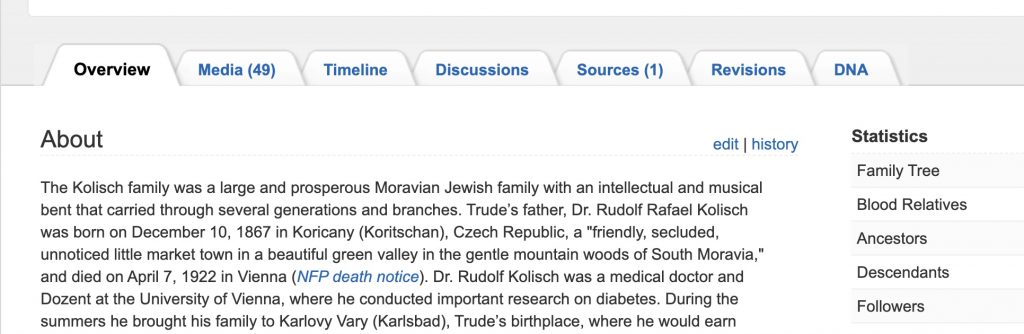

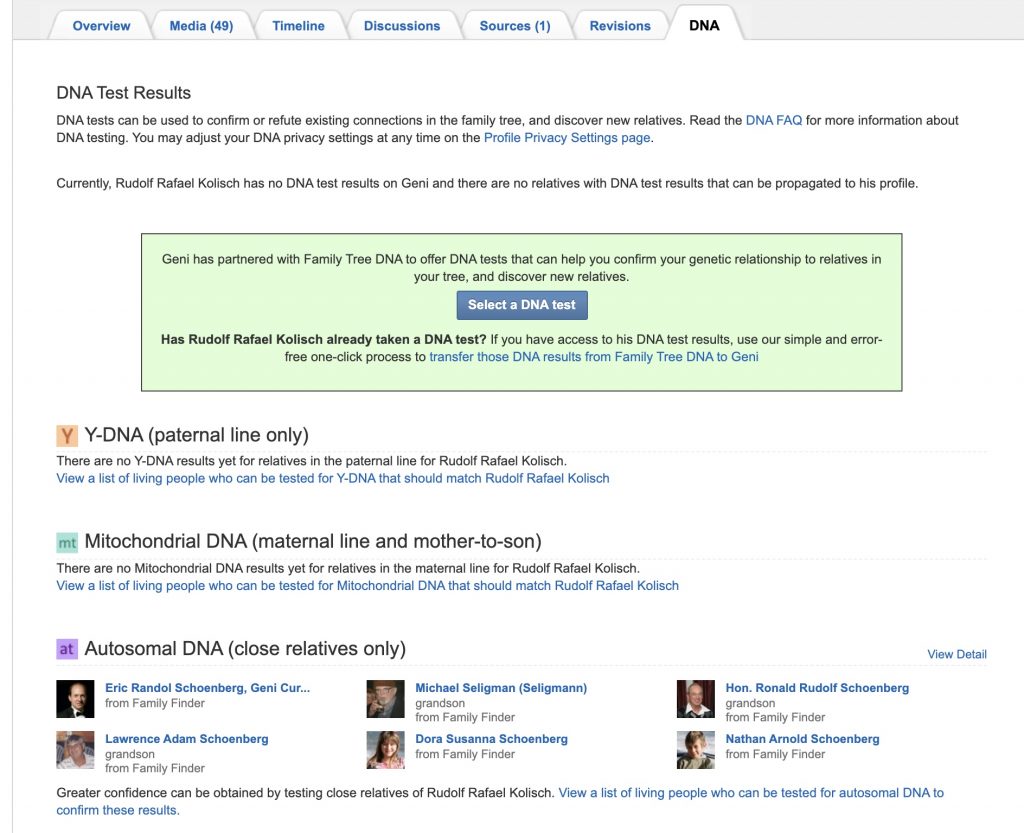

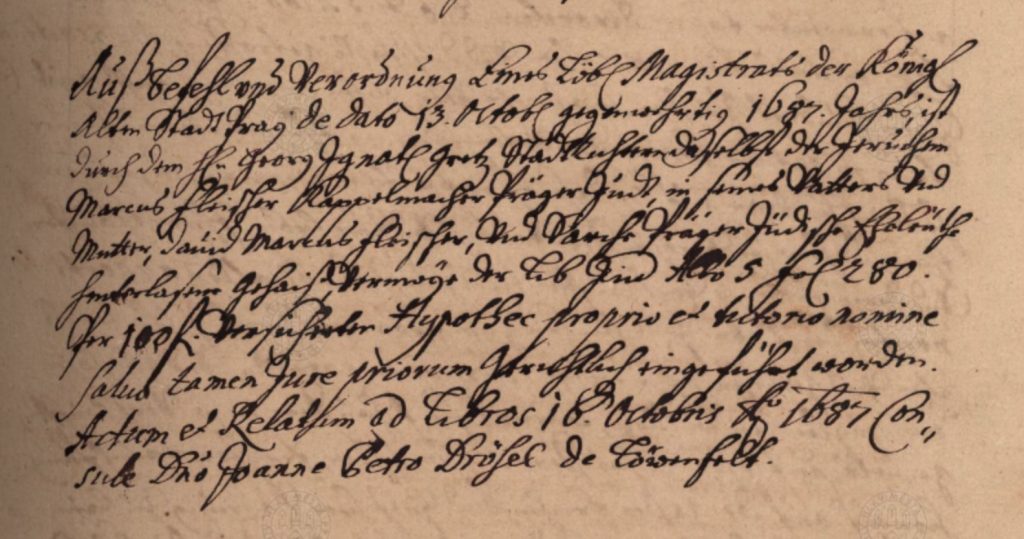

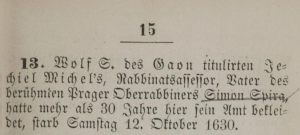

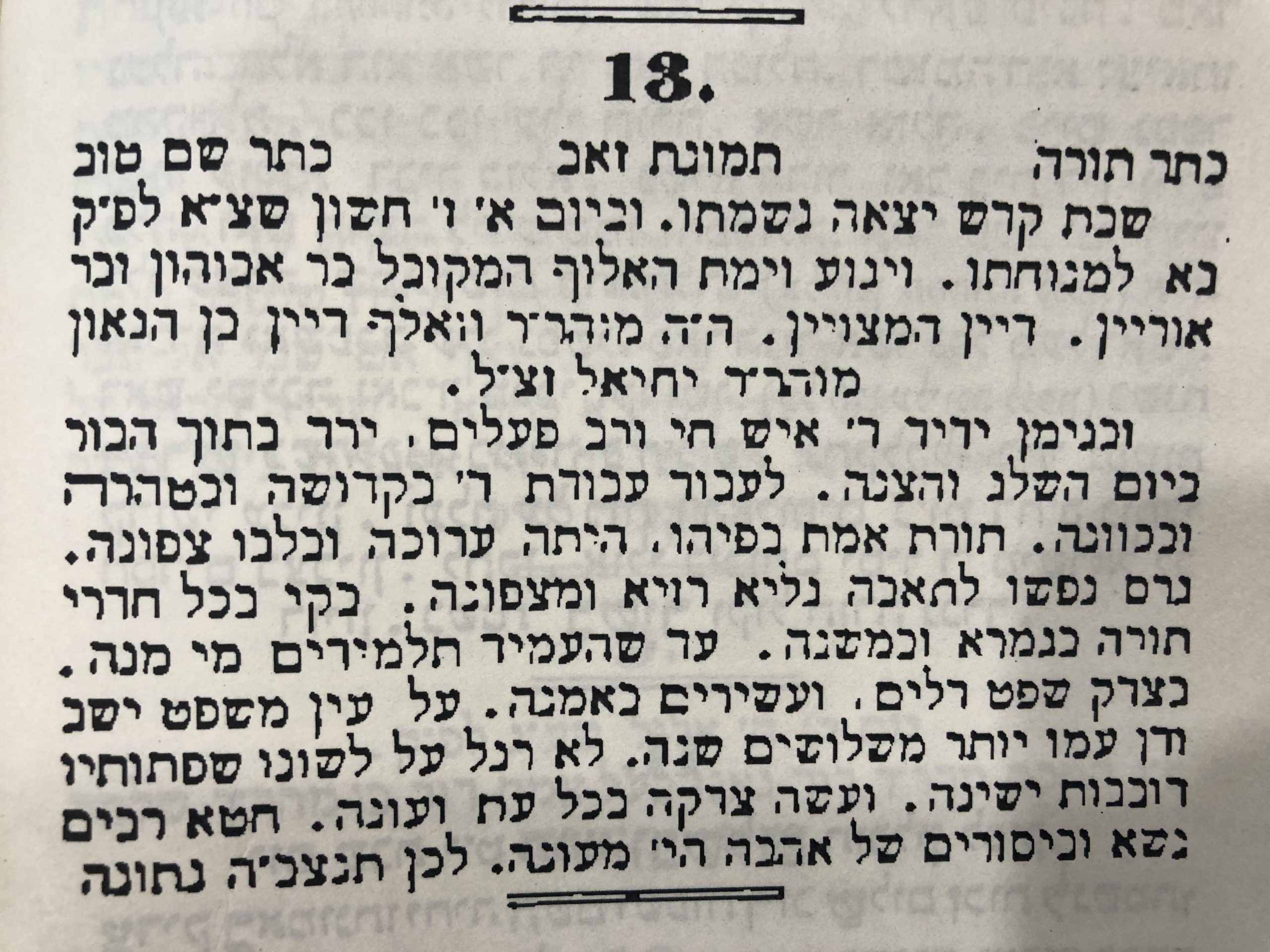

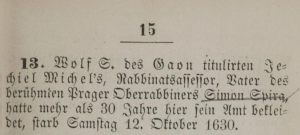

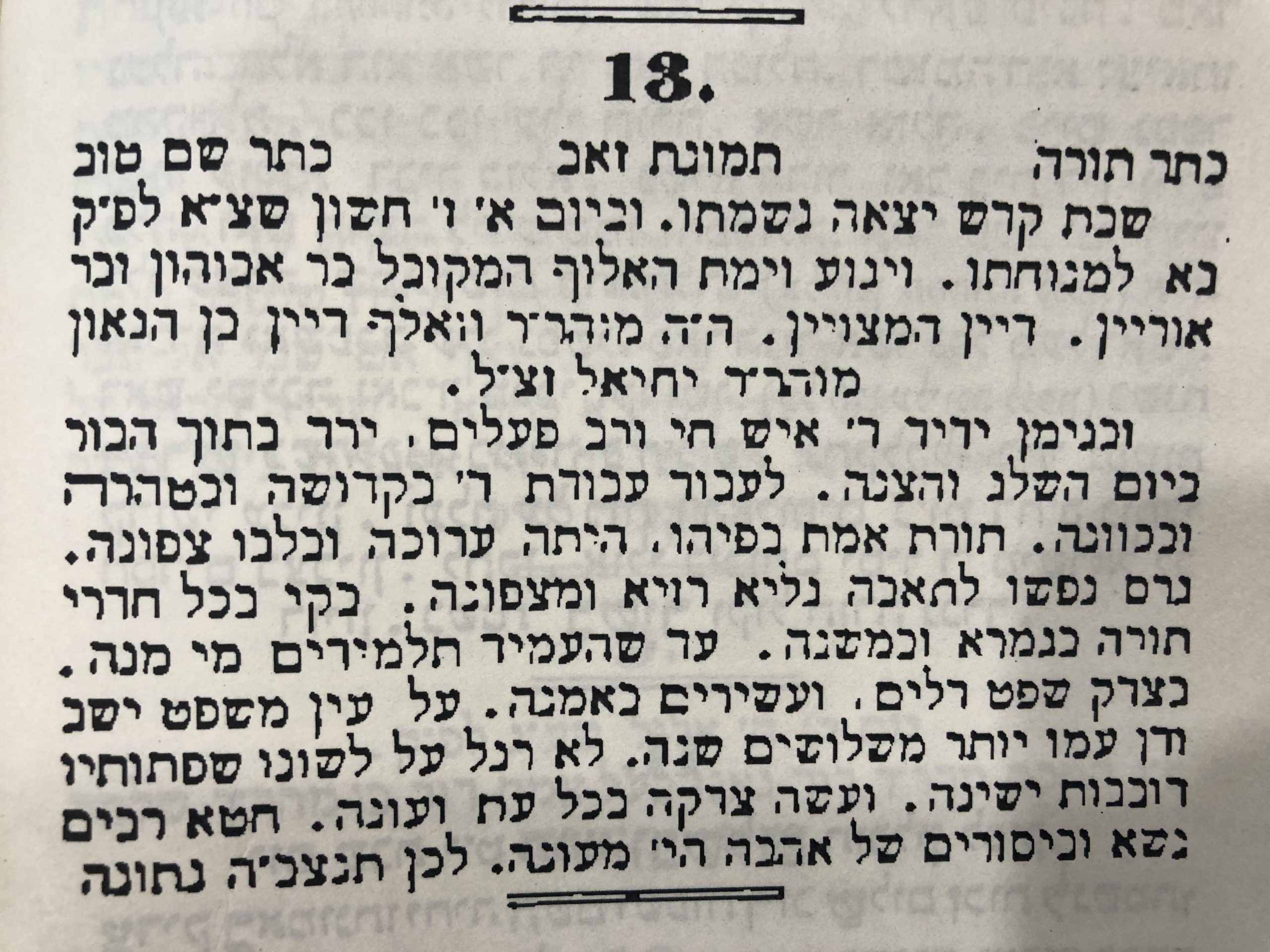

I initially approached Wolf Slawes from a completely different direction. I was working on the ancestry of the famous 19th century chess master Baron Ignatz von Kolisch of Bratislava, Slovakia whom my family has always assumed was a cousin of my grandmother Gertrud Kolisch, whose father came from Korycany, Moravia. By good fortune, I was able to trace Baron Kolisch’s paternal ancestry back to Prague, and then extended it all the way back to a Wolf Kalisch who died in Prague in 1691, the son of haGaon Menachem Man of Brisk (d. 1651 Hamburg), the son of Rabbi Yechiel (Michel) Spira, d. 1598 Prague. Researching this family, I soon discovered that Rabbi Yechiel Spira was also the father of a man known as Benjamin Wolf Slawes (d. 1630 Prague). (Benjamin and Wolf are related names, or kinnui, because the symbol of the ancient Israelite tribe of Benjamin was a wolf.) Benjamin Wolf Slawes was for more than thirty years an associate rabbi and director of the Talmudic academy in Prague, who briefly took over the chief rabbinate position when Rabbi Heller was arrested and sent to Vienna. His son, Aaron Shimon Spira Wedeles was for forty years Chief Rabbi of Prague and Bohemia. The text of Benjamin Wolf’s tombstone is published in Koppelmann Lieben’s Gal-Ed (Prague 1856), where he is called Wolf Dayan (i.e. Judge). Notably, Wolf is not identified as a Levite, and neither are any of his male line descendants.

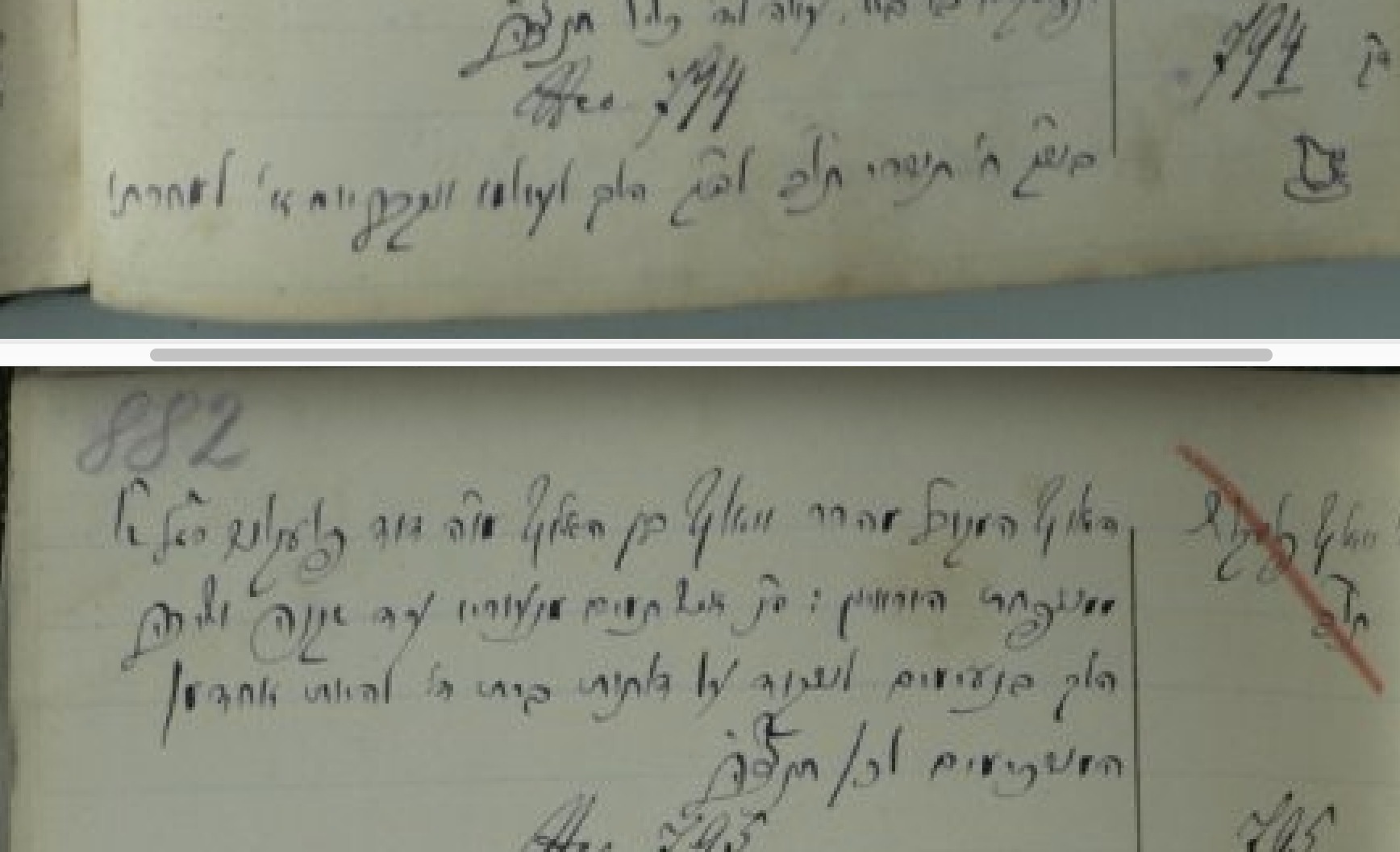

Grave inscription for Wolf Dayan son of haGaon Yechiel, October 12, 1630. Koppelmann Lieben, Gal-Ed, Grabsteininschriften des Prager Isr. Alten Friedhof, p. 15 (German), p. 6 (Hebrew) (M.J. Landau Prague 1856).

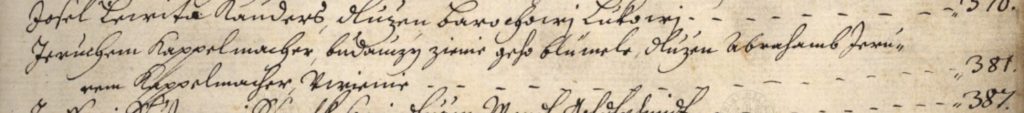

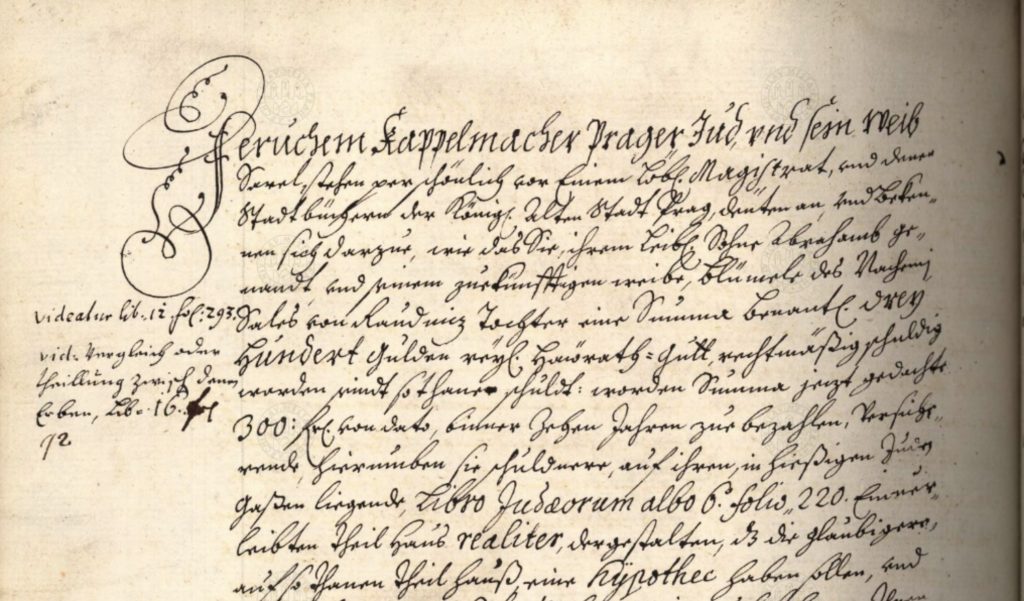

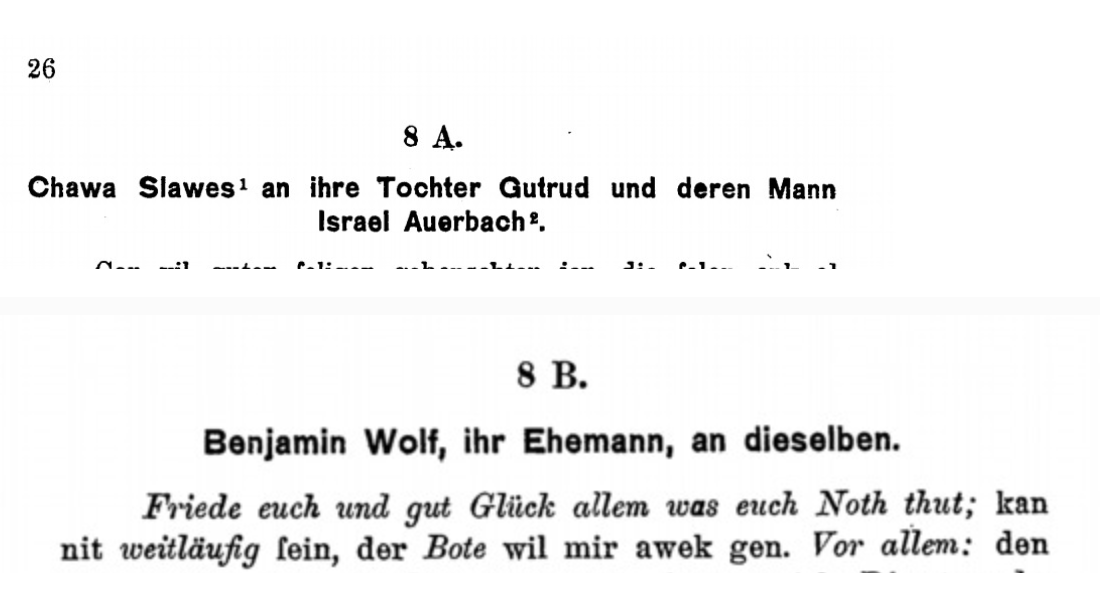

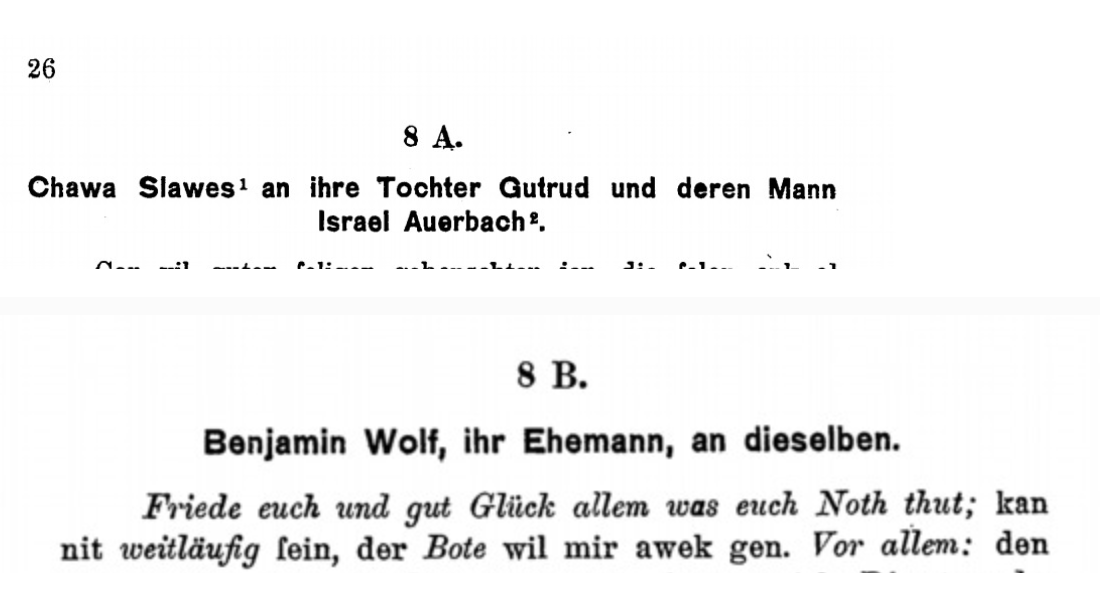

In 1911 and 1912, there were two important publications that helped further identify Wolf Slawes. In 1911, Alfred Landau and the incomparable Bernhard Wachstein published Jüdische Privatbriefe aus dem Jahre 1619. Members of the Jewish Historical Commission in Vienna had discovered in the Austrian State Archives a remarkable trove of unopened letters written by the Jews of Prague to their family members in Vienna. Somehow the letters had not been delivered, but ended up in the archives, only to be discovered almost 300 years later. Written in Judeo-deutsch, a form of Yiddish, and sometimes even in code, the letters offered a rare glimpse into the daily lives and concerns of the Jews living in early 17th century Prague and Vienna. Two of the letters published in Privatbriefe (8A and 8B) were authored by Benjamin Wolf and his wife Chawa Slawes to their daughter Gutrud and her husband Israel Auerbach. A third letter (9) was written by Benjamin Wolf to his new in-law Jekel Schick. Chawa Slawes was also the first name on item 47, a list of the authors of the letters with the sums paid to bring the letters from Prague to Vienna. It is worth noting that the Privatbriefe included two letters (20A and 20B) by Rabbi Heller and his wife Rechel to Rechel’s aunt Edel, the widow of Ahron Malkes and daughter of Rabbi Moses Ahron Theomim. Wachstein, who simultaneously published his enormous, unsurpassed volumes on the inscriptions of the old Jewish cemetery in Vienna, Die Inschriften des Alten Judenfriedhofes in Wien, was perfectly placed to identify the authors, recipients and the various family members and friends referenced in the letters.

Landau, Alfred and Bernhard Wachstein, Jüdische Privatbriefe aus dem Jahre 1619, pp. 26-27 (Wilhelm Braumüller Vienna 1911).

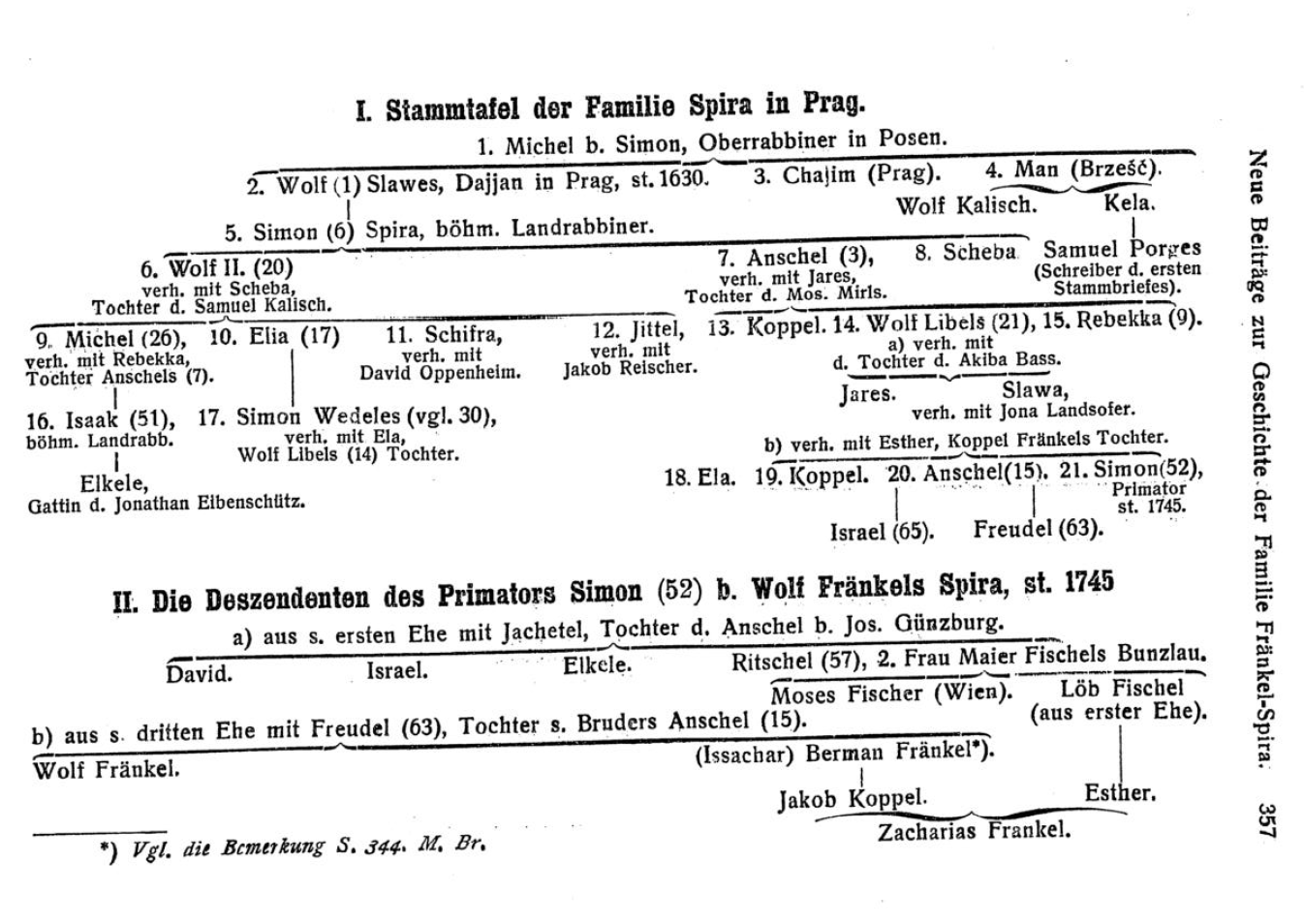

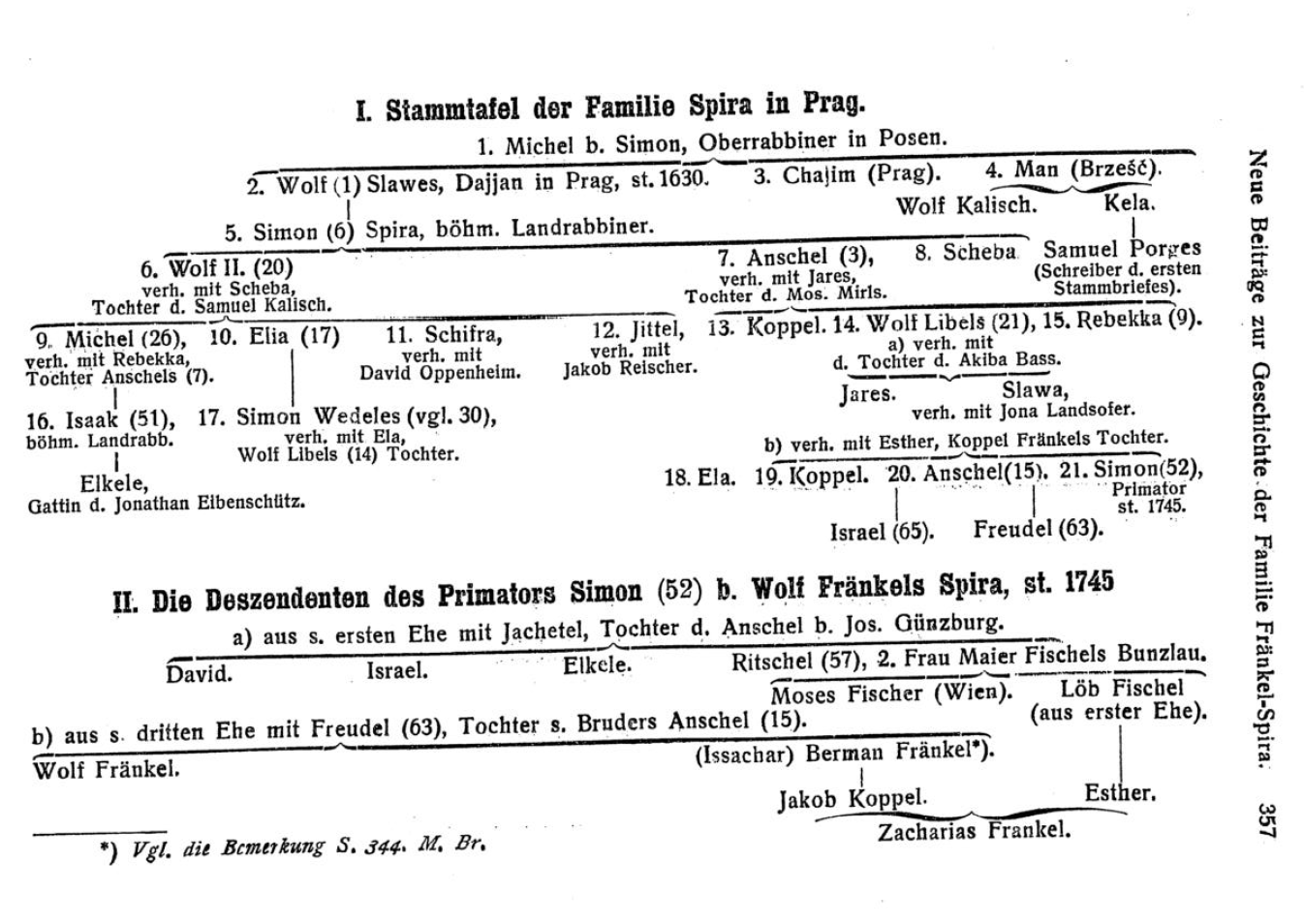

The following year, in 1912, Ludwig Lazarus published an article “Neue Beiträge zur Geschichte der Familie Fränkel-Spira,” in Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums Jahrg. 56 (N. F. 20), H. 5/6 (Mai/Juni 1912), pp. 334-358, featuring two new sources. One of these was a transcription of an old letter concerning family history written in 1734 by the elderly Samuel Porges (d. 1734), a grandson of Menachem Man of Brisk, to the Prague community elder Simon Fränkel Spira (d. 1745 Prague), a great-great-grandson of Wolf Slawes, the brother of Menachem Man. From this source, Lazarus was able to create a family tree identifying the related descendants of Jechiel (Michel) Spira, including Wolf Slawes, the father of Rabbi Simon Spira.

Ludwig Lazarus, “Neue Beiträge zur Geschichte der Familie Fränkel-Spira,” Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums Jahrg. 56 (N. F. 20), H. 5/6 (Mai/Juni 1912), pp. 334-358.

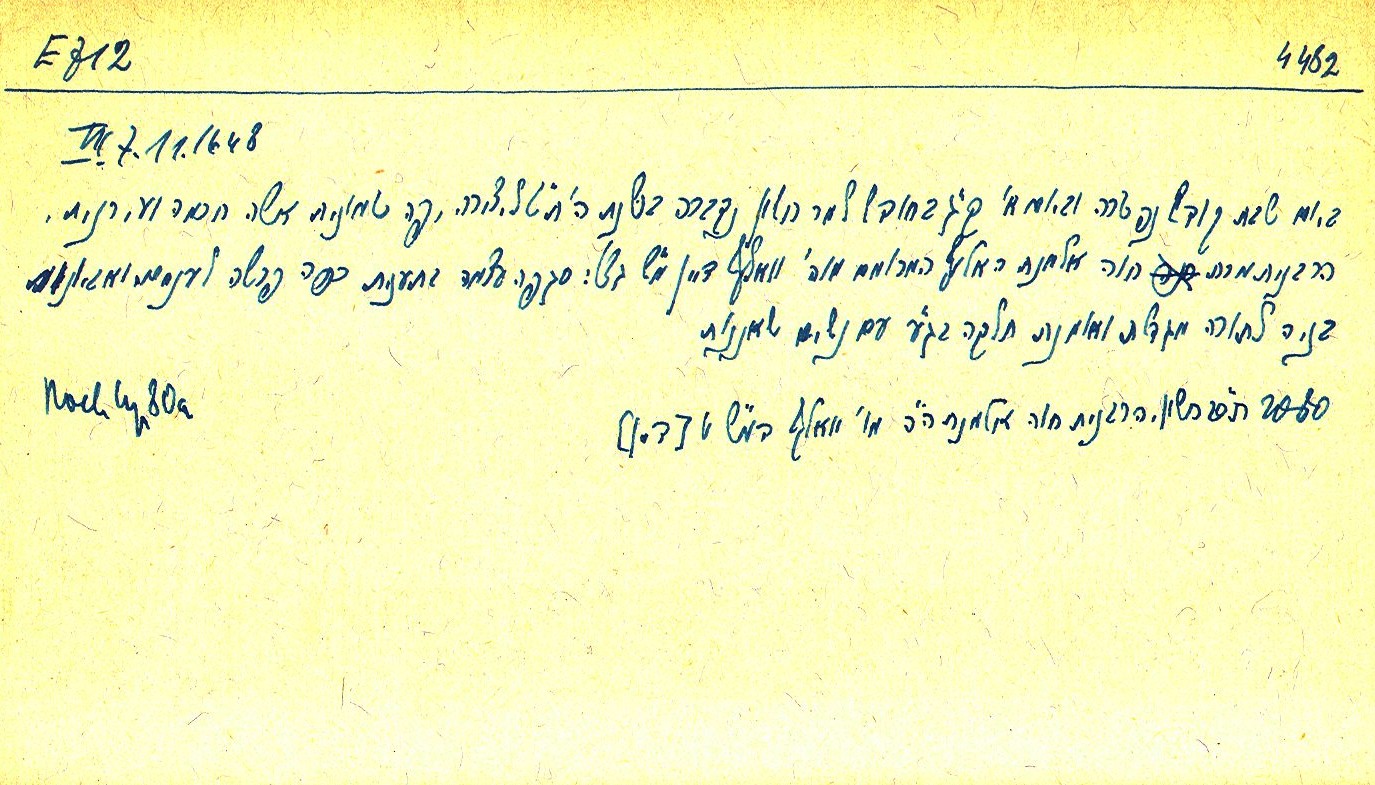

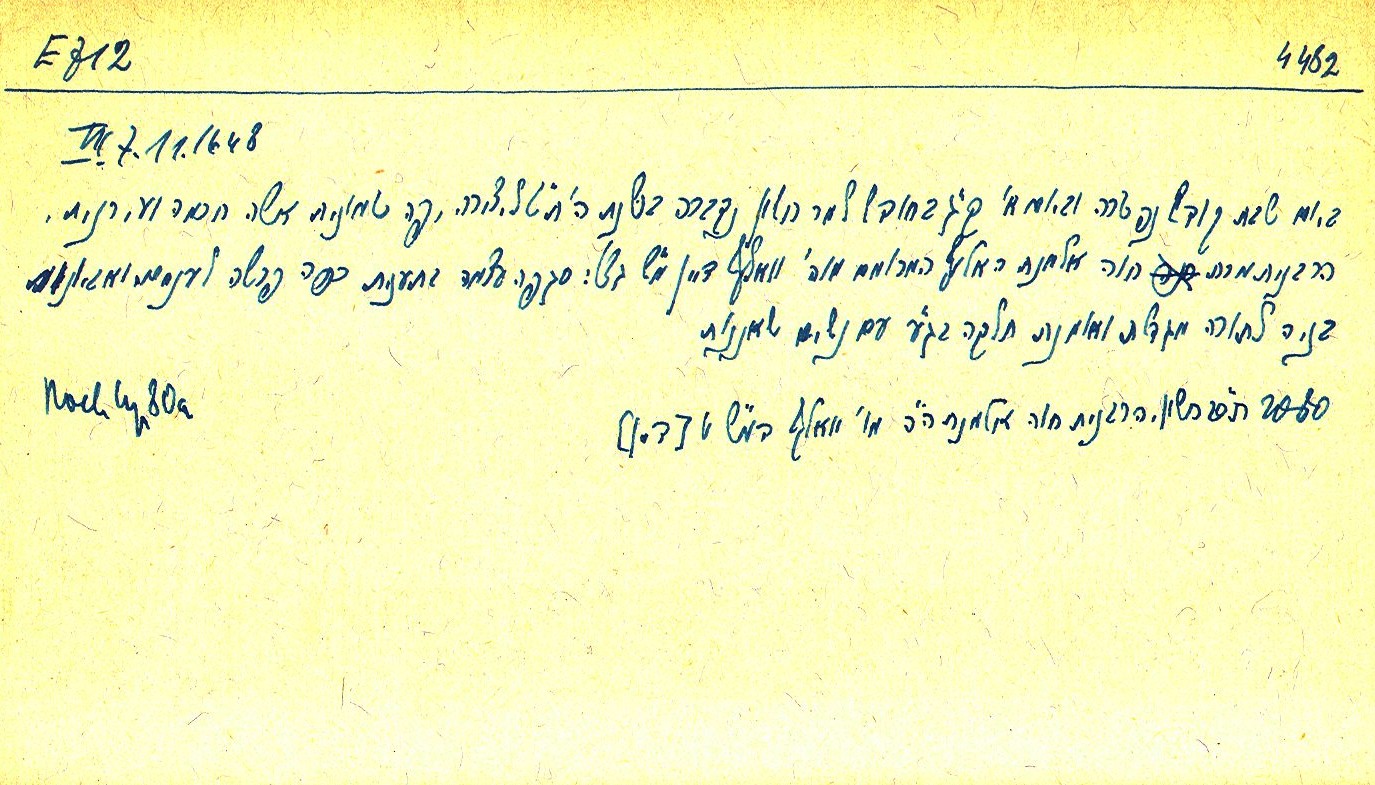

Notably, there is no mention of Rabbi Heller’s daughter Nissel, as there certainly would have been if Benjamin Wolf Slawes had been her husband. And there is no possibility that Wolf had a second wife after Chawa, because Wolf died in 1630, as we have already seen, and his wife Chawa died as a widow in 1648, as seen in this grave inscription transcribed by the Prague historian Otto Muneles (1894-1967).

Grave inscription of Chawa the widow of Wolf Dayan of the Meisel Schul November 9, 1648 by Otto Muneles, Jewish Museum Prague.

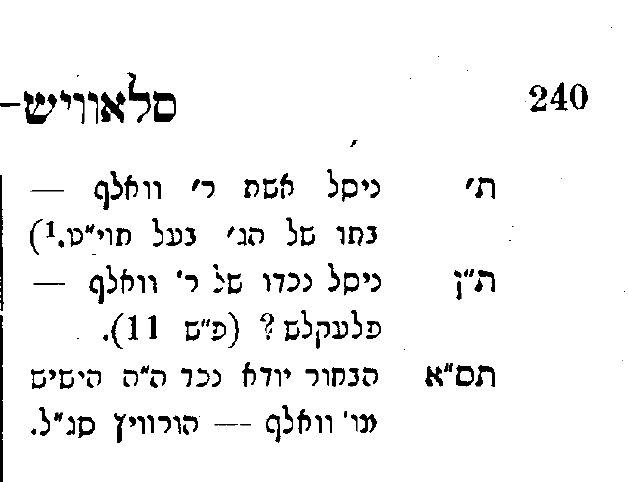

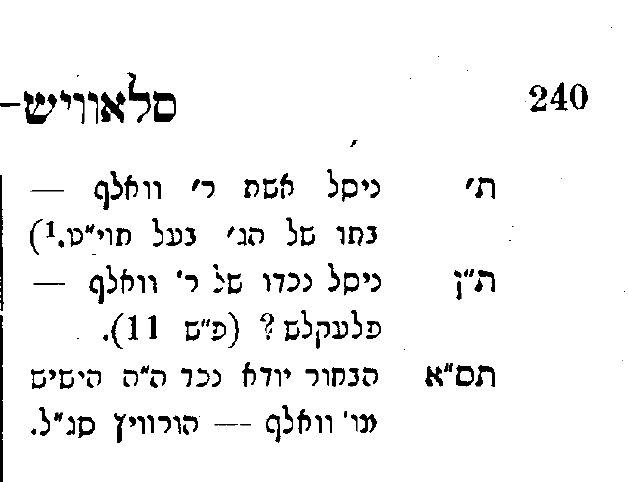

So we are left with the question, are there really two different men named Wolf Slawes living in Prague at the same time, one married to Chawa and another married to Rabbi Heller’s daughter Nissel? The answer is certainly no. First, Slawes is not a regular surname in Prague. There are pretty much no others that we find there. In the Prague cemetery book Die Familien Prags by Simon Hock (1815-1887), published posthumously in 1892 by the prolific historian David Kaufmann (1852-1899), we find on page 240 just four graves listed under the name Slawes, three of whom are identified as descendants of Rabbi Heller or Wolf Slawes. Benjamin Wolf and Chawa Slawes are not listed at all.

Simon Hock, Die Familien Prags, p. 240 (Kaufmann 1892).

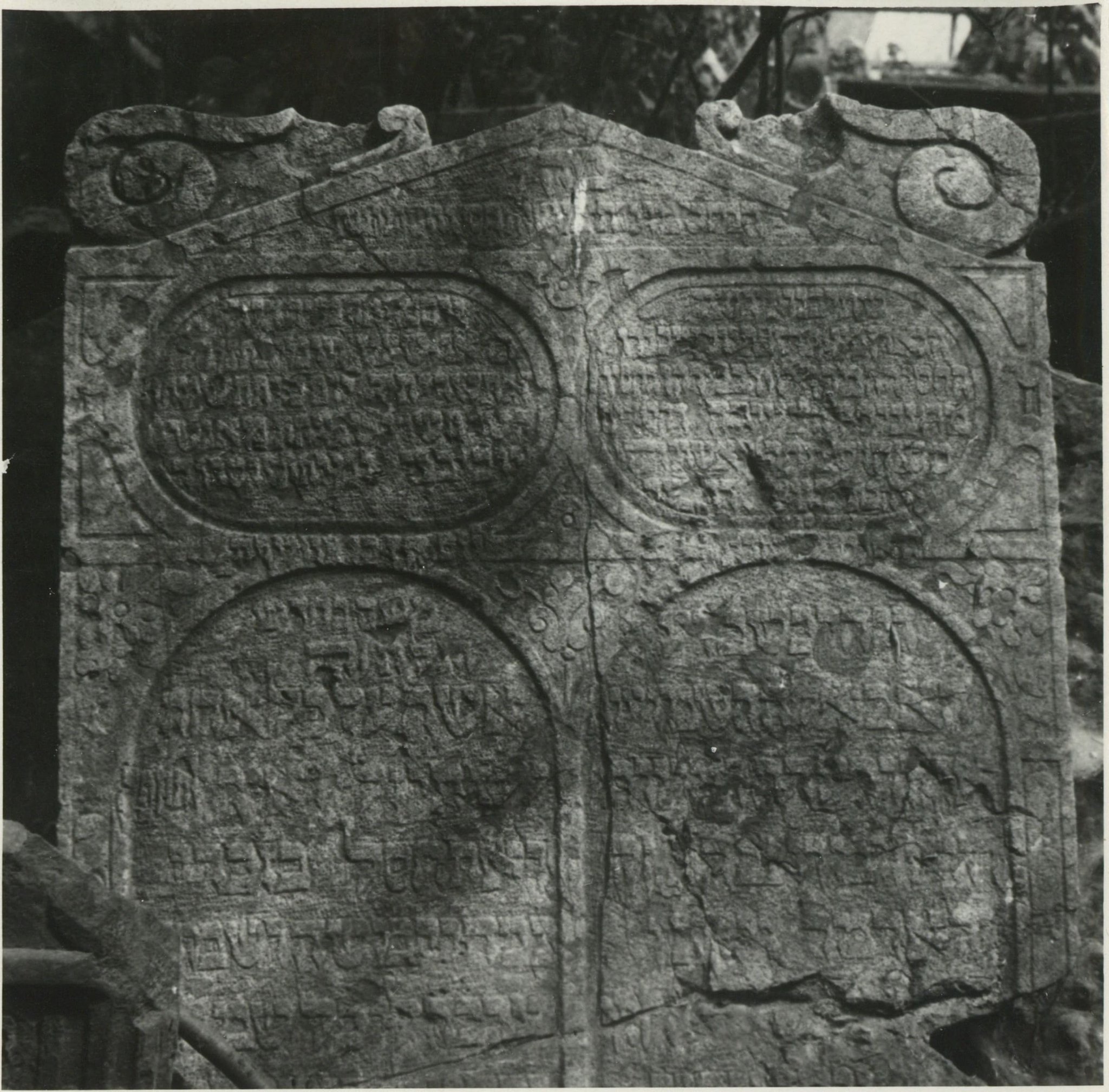

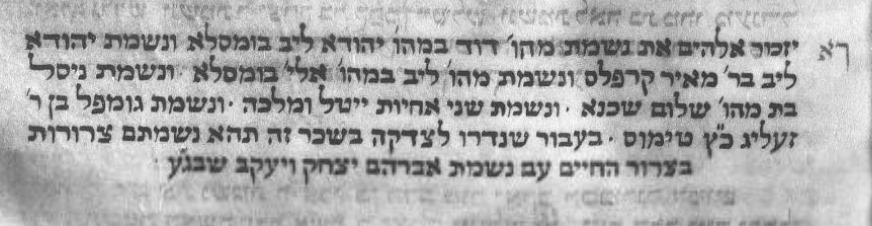

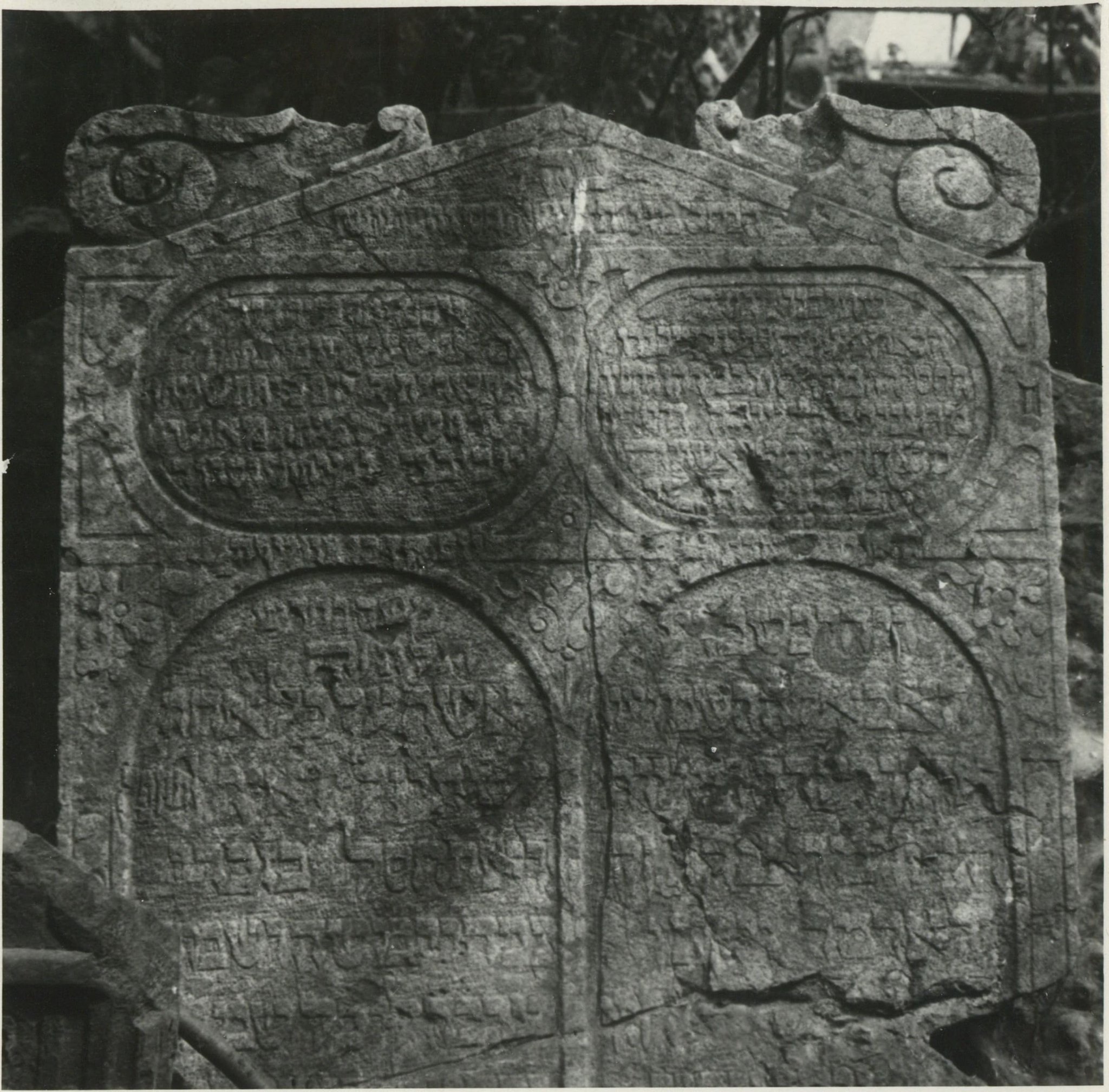

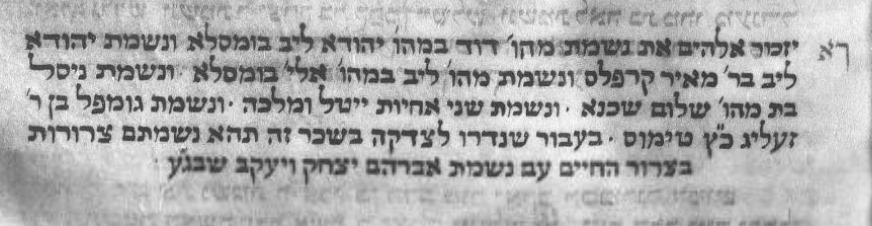

The one that easily could have resolved the mystery is the grave of Rabbi Heller’s daughter Nissel, who died October 11, 1639 in Prague. But she died during a plague year, and is buried with her sister Resel and five of Heller’s grandchildren: Moshe, Simcha, Matel, Manes and Gutrut. Rabbi Heller himself apparently wrote the elaborate, poetic grave inscription, which unfortunately, and quite unusually, does not mention the husbands of his daughters or the fathers of his grandchildren.

Grave of Nissel and Resel, daughters of Rabbi Heller, and five of Heller’s grandchildren: Moshe, Simcha, Matel, Manes and Gutrut. Courtesy of Daniel Polakovic, Jewish Museum Prague.

We know from his autobiography that Rabbi Heller attended the wedding of his grandson Nathan, the son of his daughter Nissel. Nathan’s wife was Chana the daughter of Rabbi Moshe Katzenellenbogen Wahl, Av Beit Din (Rabbinic Judge) of Chelm, the grandson of the famous “King for a Day” Saul Wahl. According to the Schick genealogy, Solomon Zvi Schick’s Mi Moshe ad Moshe (1903), which is based in part on David Tebele Efrati’s Toldot Anshei Shame (1875), Rabbi Heller’s grandson Nathan and his wife Chana were the parents of Moshe HaLevi d. 1684 Krakow and his sister Nissel, named after her grandmother, who was married to Rabbi Schmuel Schick of Pruzany.

Solomon Zvi Schick, Mi Moshe ad Moshe, p. 20 (1903).

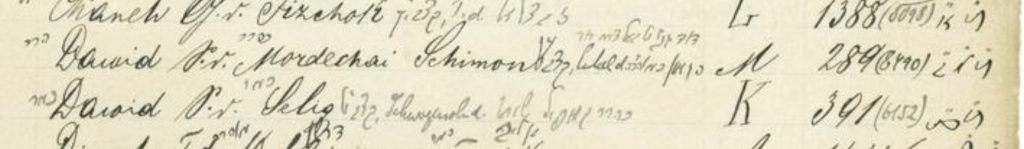

It is not certain if Nissel Schick is the same as the second Nissel identified in Hock-Kaufmann’s Die Familien Prags, who is described as Nissel, the granddaughter of Wolf Slawes Flekeles? d. 1689/90. The source provided for that entry is an early Pinkas Synagogue Memorbuch, which has not been located. No grave in Prague has been identified for this Nissel.

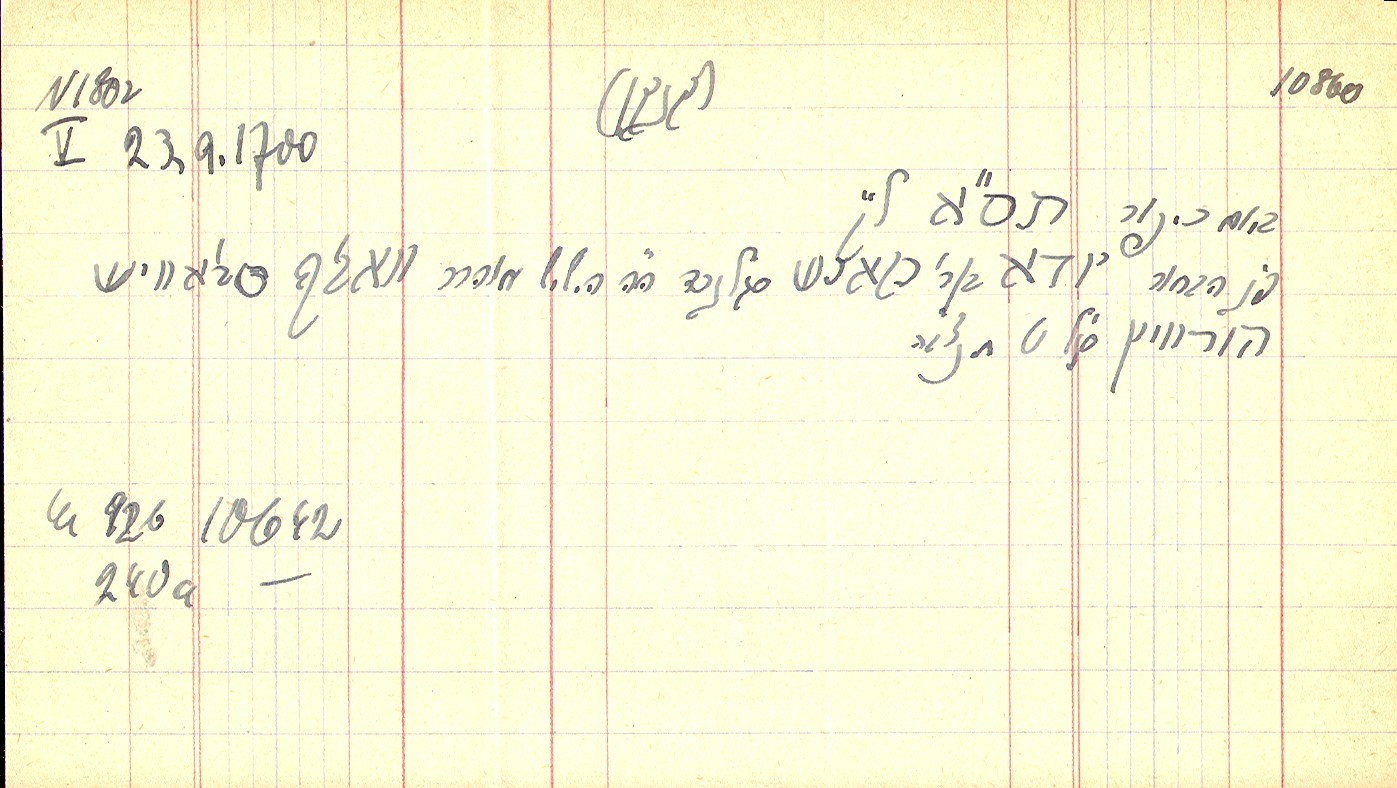

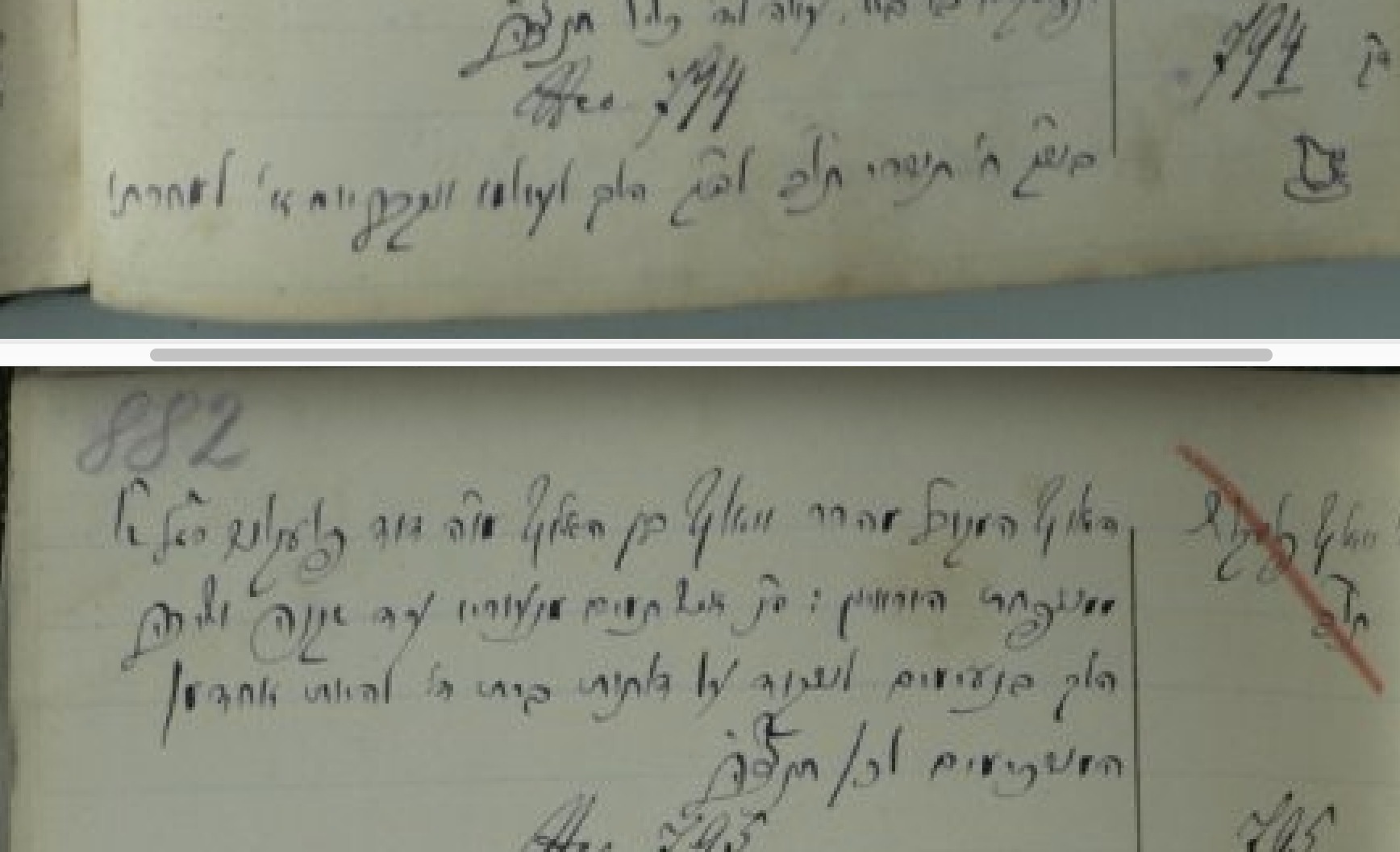

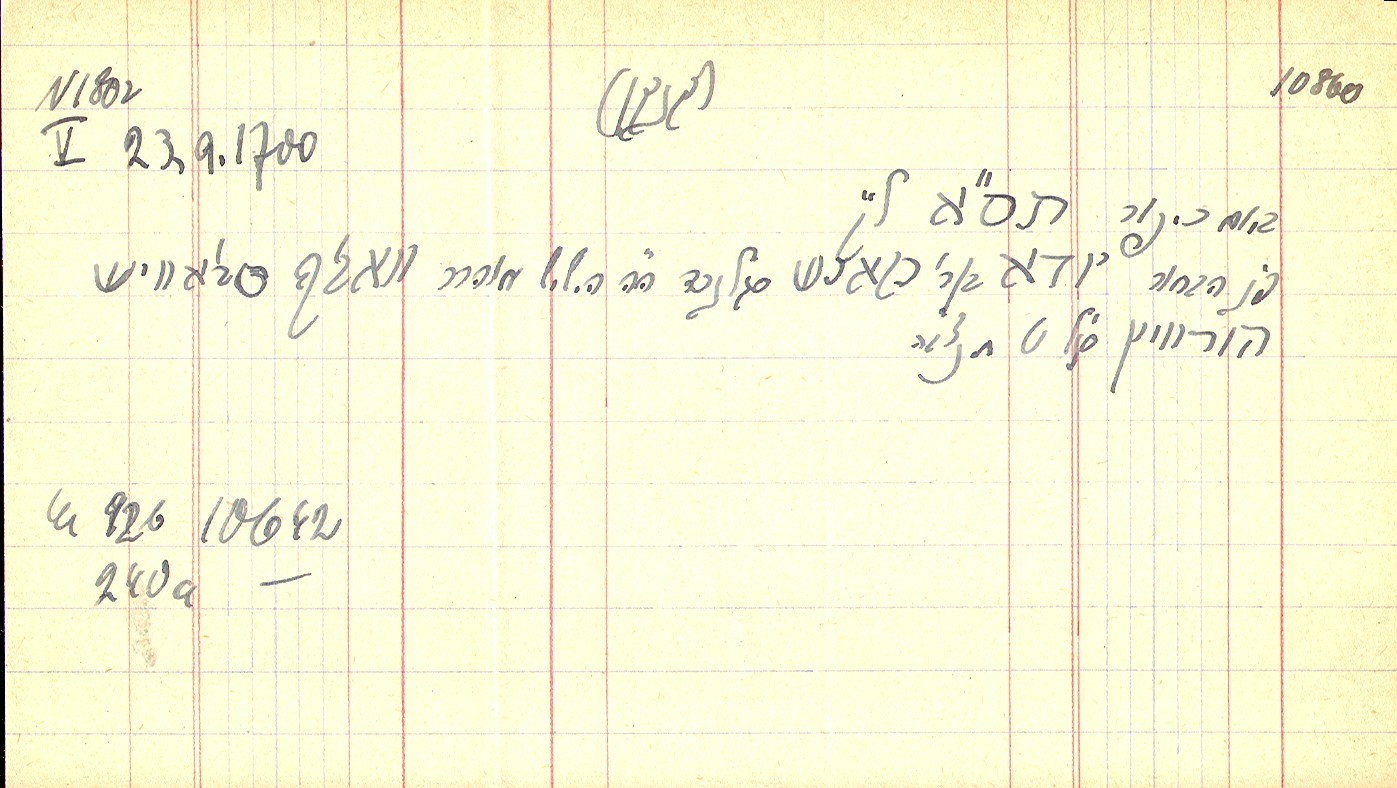

The third of these Slawes graves listed in Hock-Kaufmann refers to a young boy Juda, the son of Manes SeGal, grandson of the elderly Wolf Slawes Horowitz SeGal, who died in Prague on September 23, 1700, as recorded in the grave inscription transcribed by Otto Muneles.

Otto Muneles’ grave inscription for Juda, son of Manes SeGal, grandson of the elderly Wolf Slawes Horowitz SeGal, died September 23, 1700, Prague. Courtesy of Daniel Polakovic, Jewish Museum Prague.

The surnames Flekeles and Horowitz on the last two entries in Hock-Kaufmann’s Die Familien Prags provide clues for a solution to the problem. We find in the Prague cemetery the grave of Juda’s father Manes, who died February 20, 1707 in Prague. On his epitaph transcribed by Rabbi Leopold Popper (1826-1885), who also compiled a useful index of the graves in the old cemetery in Prague, Manes is described as the son of the deceased Jehuda SeGal Horowitz Flekeles. There is no mentioned of either Wolf Slawes or Rabbi Heller on Manes’ grave, but he very clearly was a Levite, as evidenced also by the image of a pitcher of water on the grave, a symbol for Levites.

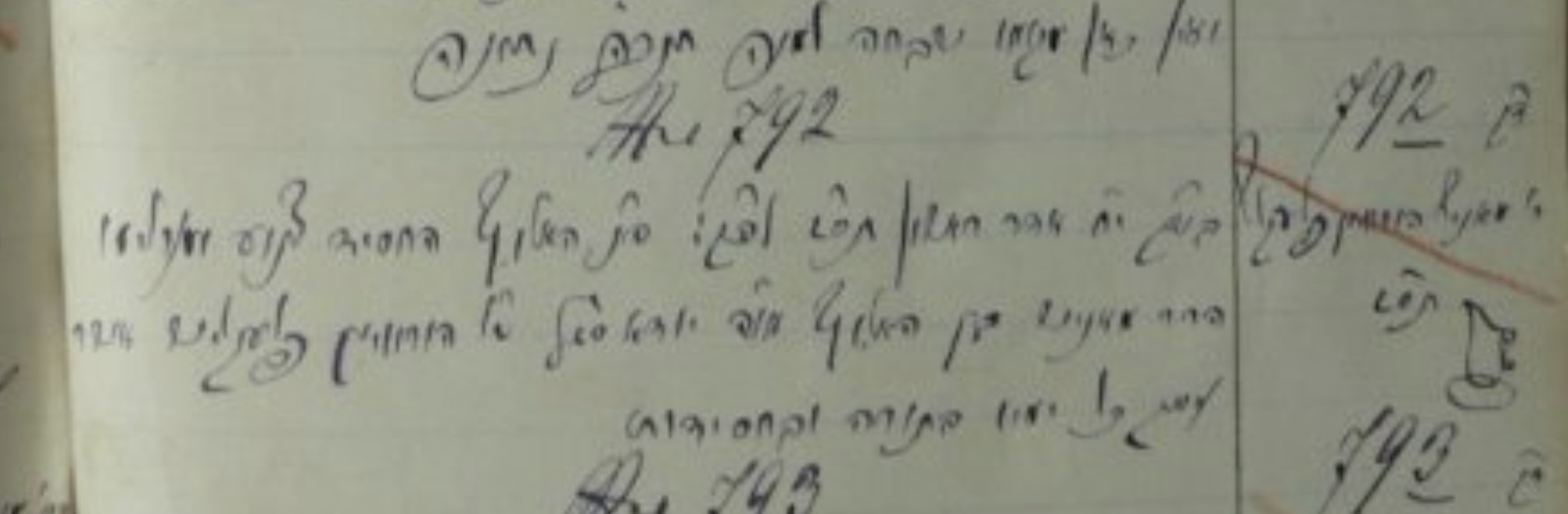

Leopold Popper’s grave inscription for Manes, son of the deceased Jehuda SeGal Horowitz Flekeles. Courtesy of Alexandr Putik, Jewish Museum Prague.

There is a grave entry in Hock-Kaufmann for Suessele, the daughter of Juda Horowitz SeGal, wife of Jekel r’Th, who dies 1688, but I have not yet discovered the grave of Manes and Suessele’s father Juda/Jehuda Horowitz Flekeles. However, we have yet another clue in the old Prague cemetery. There is yet another Nissel who dies July 14, 1726, the wife of Loeb b. Meir Karpeles and daughter of the deceased Shalom Schachne Horowitz HaLevi, grandson of the Gaon Tosafot JomTov.

Leopold Popper’s grave inscription for Nissel, the wife of Loeb b. Meir Karpeles and daughter of the deceased Shalom Schachne Horowitz HaLevi, grandson of the Gaon Tosafot JomTov, died July 14, 1726, Prague. Courtesy of Alexandr Putik, Jewish Musuem Prague.

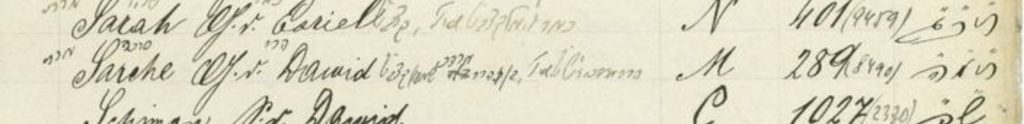

Loeb and Nissel Karpeles have a son who dies in 1720 named Shalom Schachne after his maternal grandfather. Loeb Karpeles, shammesh of the Burial Brotherhood, who died March 28, 1729, is mentioned in the Book of Seats of the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague, as follows: “R. Leb, son of R. Meir Karpeles, declared that he descended from the family of the Teomim on his wife’s side as she was the daughter of R. Schachna, grandson of Wolf Slawes, grandson [sic] of the author Tosafot Jomtob, son-in-law of R. Ahron Teomim.” Hana Volavkova, The Pinkas Synagogue, p. 136 (State Jewish Museum, Prague 1955). Nissel Karpeles is also found in a later Pinkas Synagogue Memorbuch as Nissel bat Shalom Schachne.

Nissel, daughter of Shalom Schachne, Pinkas Synagogue Memorbuch. Courtesy of Daniel Polakovic, Jewish Museum Prague.

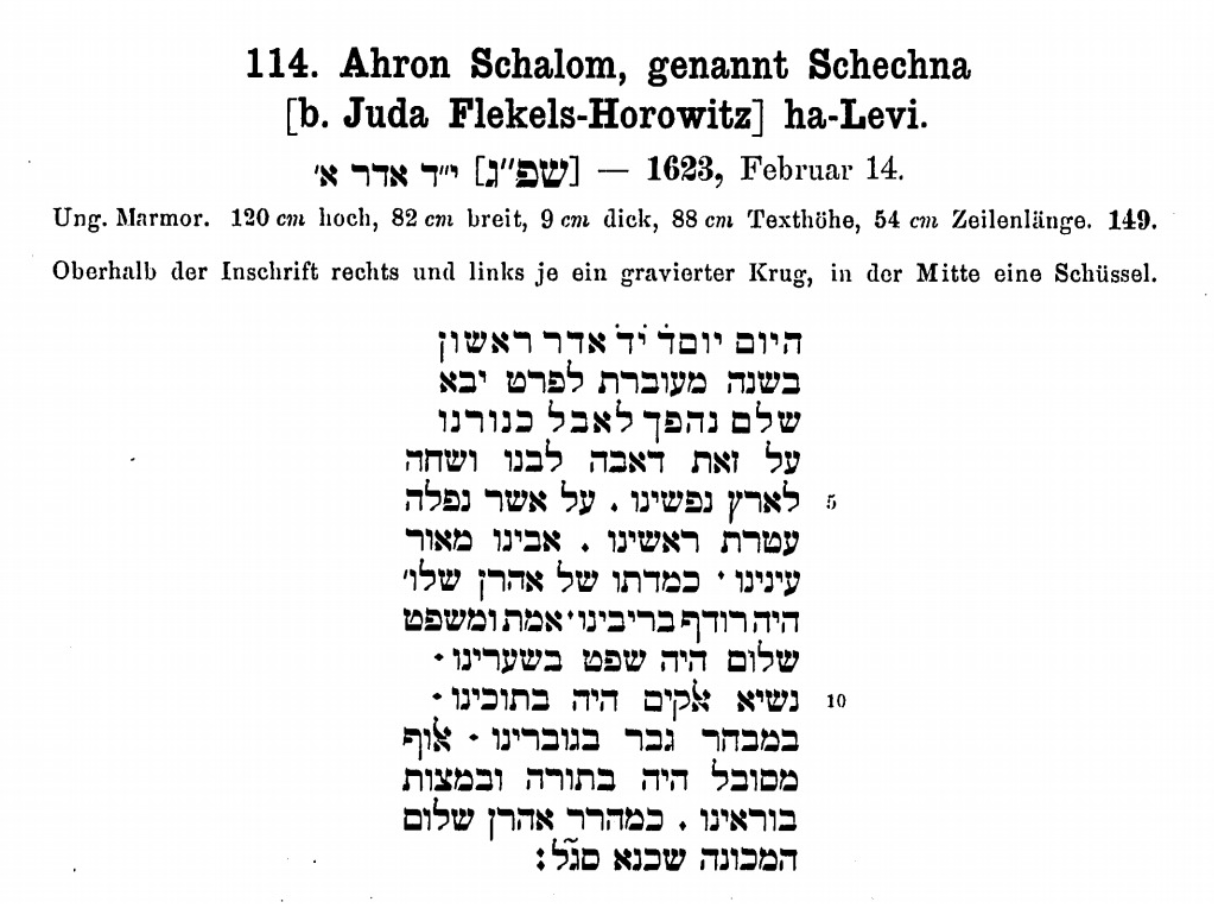

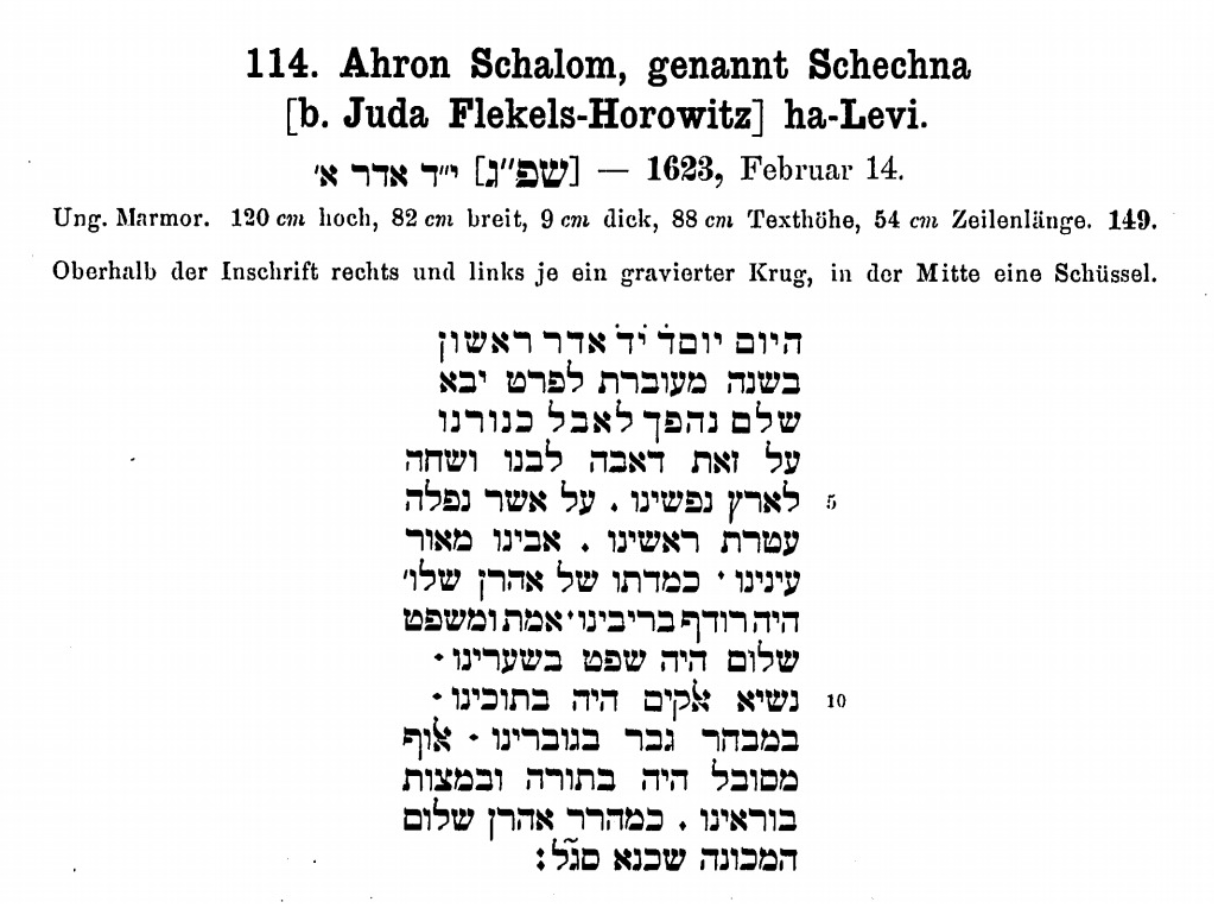

A grave for Nissel Karpeles’ father Shalom Schachne Horowitz has not been found, but his unusual name allows us to identify his family. He is without a doubt closely related and named for Ahron Schalom (called Schechna), who died February 14, 1632 in Vienna, the son of Juda Flekeles Horowitz ha-Levi.

Grave inscription of Ahron Schalom “Schechna” son of Juda Flekels-Horowitz, d. February 14, 1623 Vienna. Bernard Wachstein, Die Inschriften des Alten Judenfriedhofes in Wien, 1. Teil 1540-1670, p. 90 (1912).

Schechna is mentioned in the Privatbriefe as the recipient of two letters (36 and 37) from his sister Blümel in Prague. Schechna’s wife Edel Auerbach is also the niece of Israel Auerbach, the son-in-law of Wolf and Chawa Slawes. We don’t know of any surviving children born to Edel and Schechna, but Schechna and Blümel did have a brother David, who may have died relatively young in 1602. His grave inscription is described in Hock-Kaufmann, p. 274, as “David bn Juda haLevi seGal Flekeles z”l, ish Horwitz.” David apparently had at least four children, Hirsch d. 1605, Pessel d. 1636, Hindl d. 1639 and Wolf d. September 12, 1671. (These dates work if David died relatively young, his son Hirsch died young, and his son Wolf died very old, which needs to be checked against their full grave inscriptions.) Wolf’s epitaph transcribed by Popper reads “On Shabbat, 8 Tishri 1671 (died) and the next day, Sunday, was buried the precious and learned in Kabbala mhr”r Wolf son of mv”h David Flekeles seGal z”l m’mishpachot Horwitz.”

Grave inscription by Leopold Popper for Wolf son of David Flekeles Horowitz, died September 12, 1671. Courtesy of Alexandr Putik, Jewish Museum Prague.

This Wolf, the son of David Flekeles Horowitz, appears to me quite certain to be the real husband of Rabbi Heller’s daughter Nissel. Unlike Wolf Slawes, Wolf Flekeles Horowitz is a Levite. He was much younger than the older Wolf Slawes, who is much more likely to be the one who paid the ransom for Rabbi Heller in 1629. The younger Wolf outlived Nissel, who died young in 1639. He and Nissel should be the parents of: (1) Nathan, the father of Nissel Schick; (2) Juda, the father of Manes and Suessele, and grandfather of Manes’s son Juda; and (3) Shalom Schachne, the father of Nissel Karpeles. This solution would explain the references to Horowitz and Flekeles on the various graves of the descendants of Wolf who also are descendants of Rabbi Heller.

I have not seen the actual graves of Wolf’s great-grandson Juda b. Manes who died in 1700, but if the transcription by Muneles is accurate, it means that already by 1700, twenty-nine years after Wolf Flekeles Horowitz had died, his family had confused him with the Wolf Slawes in Rabbi Heller’s autobiography. What makes this remarkable is that Juda’s father Manes, Wolf’s grandson, was still alive when Juda died. However, one must remember that Wolf’s wife Nissel died young in the plague year 1639, so it is possible that their children, including Manes’ father Juda, were raised by someone else, perhaps by someone in Nissel’s family, rather than Wolf’s. This might also explain why we have not yet located graves for any of Wolf and Nissel’s children. Clearly, Loeb Karpeles, who had married into the family, was also under this mistaken impression when he gave his declaration to the Pinkas Synagogue for the Book of Seats. The various versions of the autobiography that were passed down and later published must have reinforced and repeated the error.

The confusion in the family makes sense if one remembers that Rabbi Heller commanded his descendants to read his autobiography. The name Wolf Slawes was perpetuated only in the autobiography and so it was grafted onto Nissel’s husband Wolf by mistake. In the family of the actual Wolf Slawes, who was apparently known by the name of his wife’s mother Slawa, the Slawes surname was not perpetuated. Nothing is known about Chawa’s mother Slawa, unfortunately, but the Slawa name does appear among the descendants of Wolf Slawes, for example the granddaughter of Rabbi Ahron, Slawa Neustädtl, or his great-granddaughter Schlawa Bunzel. Wolf’s grave does not mention the surname Slawes, only the occupational name Dayan (Judge), and already his daughter Bune Perlhefter‘s grave from 1660 in Prague referred to her father as “Wolf Wedeles,” using a surname adopted by her brother Rabbi Ahron Simon.

This analysis requires a change in the traditional genealogy of the Schick family, who refer to the descendants of Wolf and Nissel under the surname Heller. Other than the various 19th and 20th century genealogies based on the mistaken identification of Nissel’s husband Wolf, there is no evidence to support the use of the Heller surname for Nissel’s husband or her descendants. These descendants should however be pleased to find a connection to the Flekeles-Horowitz family.

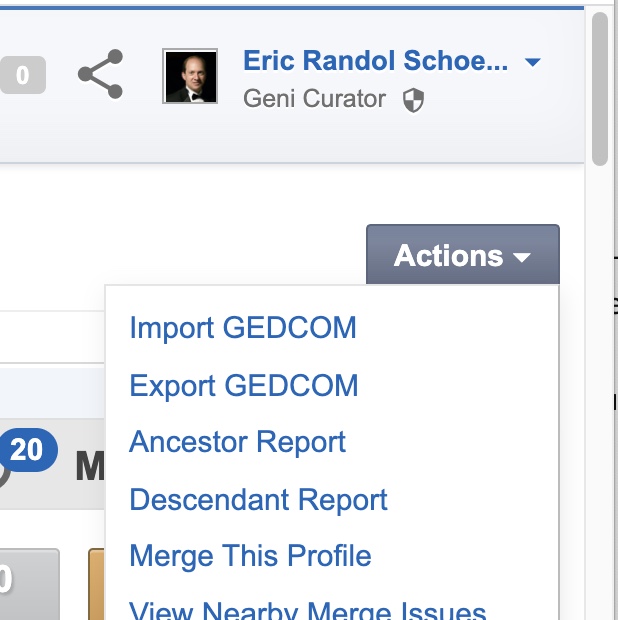

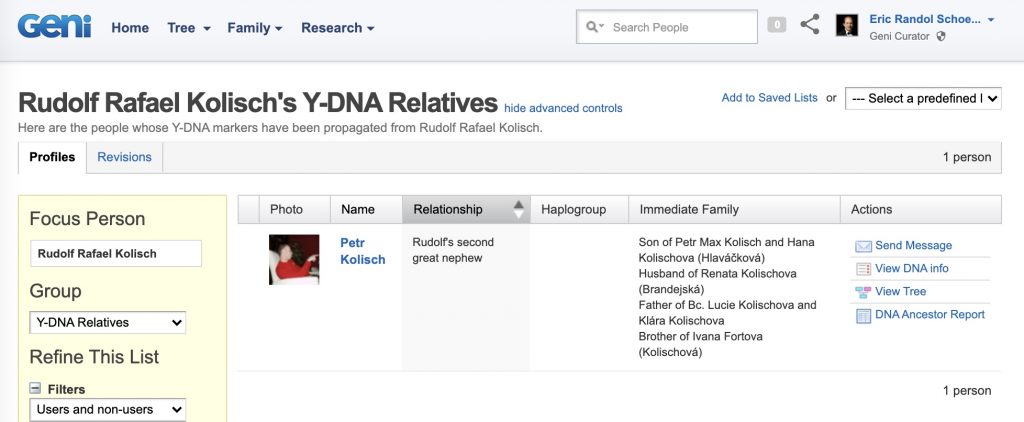

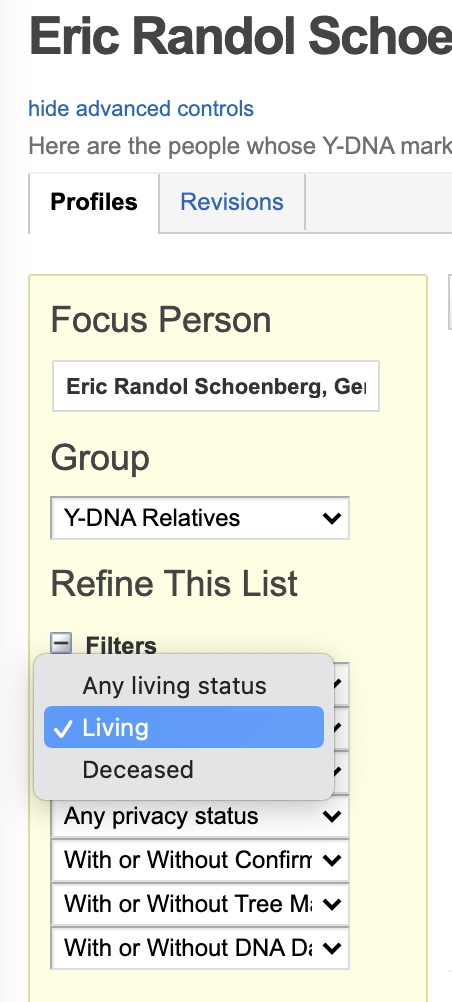

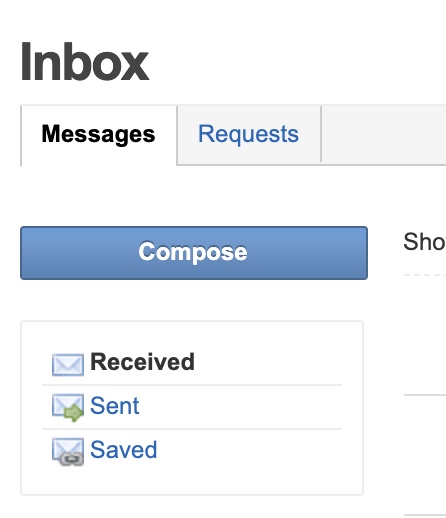

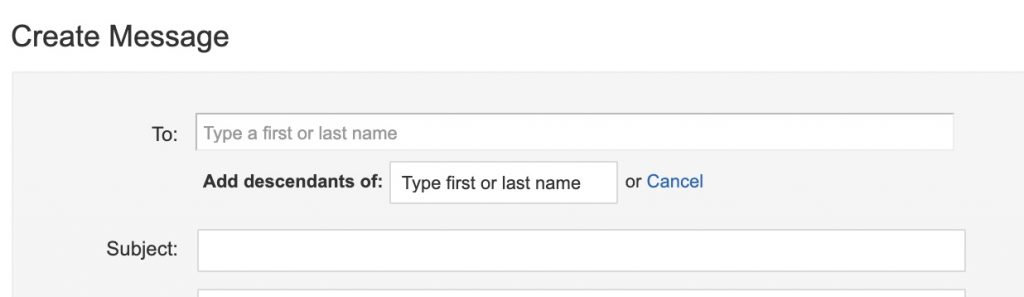

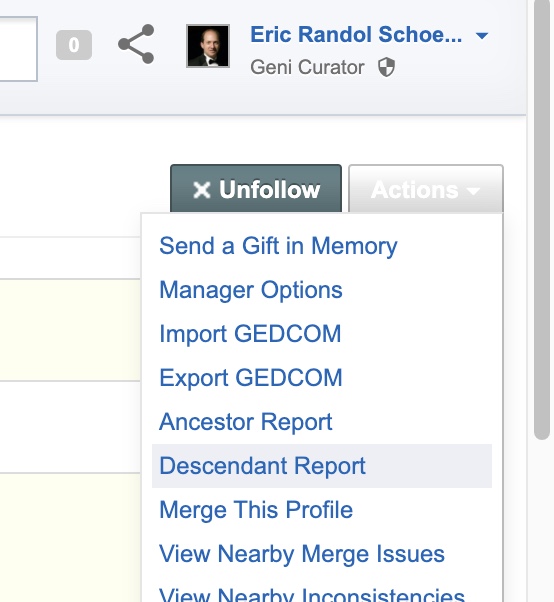

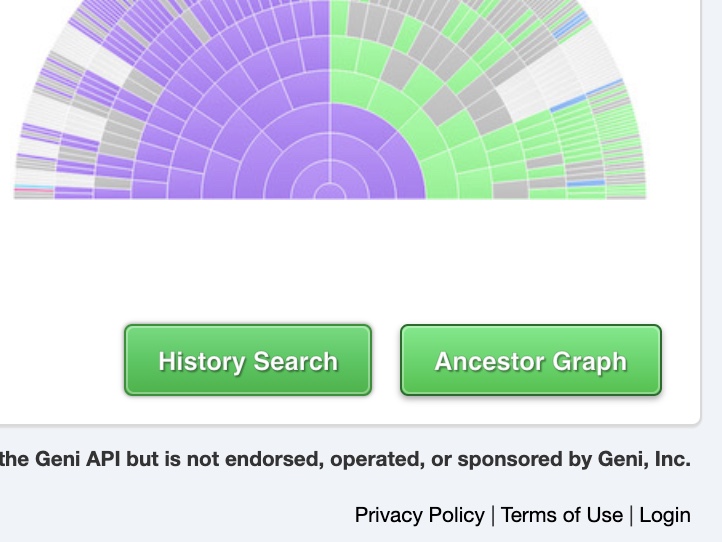

Postscript: For me, genealogy is a collaborative project and I wish to thank the many people who assisted me as I attempted to solve the puzzle of Wolf Slawes. I have had the benefit of consulting with Alexandr Putik and Daniel Polakovic at the Jewish Museum of Prague, who provided some of the grave inscriptions. My Internet friends Nancy and Thomas High in Brookline, Mass. work tirelessly on the old Popper notebooks for the Prague old cemetery and helped me decipher Hebrew inscriptions. On Geni.com, I am assisted by hundreds of researchers in this field, each with special skills, including Mayer Bar, Hatte Blejer, Adam Cherson, Bella Doron, and Samuel Royde. You can see the twists and turn in our Geni discussion. I am certain we will continue to uncover new materials to enhance or modify our conclusions. That is how progress is made.