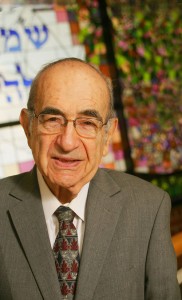

The venerable Rabbi Harold Schulweis, who passed away this week, was a beloved leader of the Los Angels Jewish community. I heard his sermons at bar mitzvahs when I was growing up, and much later had a chance to meet him when he invited me to give a talk on the Klimt case at Valley Beth Shalom. He was a super, kind, intellectual rabbi. And yet, I occasionally found myself disagreeing quite strongly with him, as I did when he wrongly spoke out against the Los Angeles Opera’s performance of Wagner’s Ring cycle, which I had supported in an Op-Ed.

On the day before he died, the Jewish Journal published a poem by Rabbi Schulweis concerning genocide and violence against African Americans, written for this past year’s high holiday services. It begins with the familiar schoolyard trope “Sticks and stones may break my bones / But names will never harm me.” Never mind that the version I grew up with ended with “But words can never hurt me.” I have always found comfort and strength in this mantra, and it dove-tails nicely with my libertarian views supporting the First Amendment.

But not Schulweiss: “False, false we Jews have learned” is his next line before he goes on a tirade against hate speech, which he says “materializes into lethal weapons,” invoking the Holocaust and all subsequent genocides (47 in number, he says), a “litany of civilizations’ broken covenant.”

False? My favorite schoolyard saying is false? And worse, it leads directly to massacres, rapes, torture and genocide?

I don’t think so. Schulweis, may he rest in peace, completely missed the point of “Sticks and stones.” The saying was never meant as a license to hurl insults. Rather, it is all about defense. “But words can never hurt me.” Not you, me. Of course words can hurt. That’s what everyone feels. But the saying teaches us to deflect the injury — not to let words hurt you. By doing so, you regain the upper hand, without stooping to the same level as your attacker. My opponent’s words have no effect on me. They cannot hurt me. I am above being hurt by words. So go on and hurl insults. I have nothing to fear from you.

How noble a sentiment. How empowering. And how Jewish! For thousands of years we have been insulted and taunted. Has it stopped us? Has it caused us to discard our faith? Our people? No. Words can never do that.

What exactly is Rabbi Schulweis preaching? That we should treat hate speech like a hurled stone? That we should fight back? That violence is the appropriate response to words that hurt us? After all, if words are so hurtful and dangerous that they can lead to genocide, wouldn’t they deserve our greatest sanction? The schoolboy who punches the kid who taunts and teases him would have every justification. After all, the words hurt.

There is no denying that sticks and stones can break our bones. Against those we must defend differently. But words can be neutralized and defeated without resorting to counterattacks and violence. That is what we should try to teach our children.

Heinrich Heine was a better poet and I like his line better: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.” For my taste, that’s the more Jewish outlook. Think of all the murder done by people who want to protect the world from people who say things they don’t like. Isn’t that the real source of genocide?

The great Jewish Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis understood this, perhaps better than Rabbi Schulweis, when he wrote the following concurring opinion in Whitney v. California (1927), which I find still valid and truly inspiring, notwithstanding the Holocaust and 47 smaller genocides that followed it. Rabbi Schulweis was an amazing person. But I am sorry to say his last poem got it wrong.

MR. JUSTICE BRANDEIS, concurring.

Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties, and that, in its government, the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end, and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness, and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that, without free speech and assembly, discussion would be futile; that, with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government. They recognized the risks to which all human institutions are subject. But they knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones. Believing in the power of reason as applied through public discussion, they eschewed silence coerced by law — the argument of force in its worst form. Recognizing the occasional tyrannies of governing majorities, they amended the Constitution so that free speech and assembly should be guaranteed.

Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech and assembly. Men feared witches and burnt women. It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears. To justify suppression of free speech, there must be reasonable ground to fear that serious evil will result if free speech is practiced. There must be reasonable ground to believe that the danger apprehended is imminent. There must be reasonable ground to believe that the evil to be prevented is a serious one. Every denunciation of existing law tends in some measure to increase the probability that there will be violation of it. Condonation of a breach enhances the probability. Expressions of approval add to the probability. Propagation of the criminal state of mind by teaching syndicalism increases it. Advocacy of law-breaking heightens it still further. But even advocacy of violation, however reprehensible morally, is not a justification for denying free speech where the advocacy falls short of incitement and there is nothing to indicate that the advocacy would be immediately acted on. The wide difference between advocacy and incitement, between preparation and attempt, between assembling and conspiracy, must be borne in mind. In order to support a finding of clear and present danger, it must be shown either that immediate serious violence was to be expected or was advocated, or that the past conduct furnished reason to believe that such advocacy was then contemplated.

Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the processes of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence. Only an emergency can justify repression. Such must be the rule if authority is to be reconciled with freedom. Such, in my opinion, is the command of the Constitution. It is therefore always open to Americans to challenge a law abridging free speech and assembly by showing that there was no emergency justifying it.

Moreover, even imminent danger cannot justify resort to prohibition of these functions essential to effective democracy unless the evil apprehended is relatively serious. Prohibition of free speech and assembly is a measure so stringent that it would be inappropriate as the means for averting a relatively trivial harm to society. A police measure may be unconstitutional merely because the remedy, although effective as means of protection, is unduly harsh or oppressive. Thus, a State might, in the exercise of its police power, make any trespass upon the land of another a crime, regardless of the results or of the intent or purpose of the trespasser. It might, also, punish an attempt, a conspiracy, or an incitement to commit the trespass. But it is hardly conceivable that this Court would hold constitutional a statute which punished as a felony the mere voluntary assembly with a society formed to teach that pedestrians had the moral right to cross unenclosed, unposted, wastelands and to advocate their doing so, even if there was imminent danger that advocacy would lead to a trespass. The fact that speech is likely to result in some violence or in destruction of property is not enough to justify its suppression. There must be the probability of serious injury to the State. Among free men, the deterrents ordinarily to be applied to prevent crime are education and punishment for violations of the law, not abridgment of the rights of free speech and assembly.