One of the things I most like about genealogy is the ability to discover the often forgotten history of our ancestors and their Jewish communities. This year, a breakthrough on a branch of my family tree in Prague led me to an amazing discovery of a long-forgotten family tradition that we’ll be celebrating again this year on December 30 (22 Tevet).

One of the things I most like about genealogy is the ability to discover the often forgotten history of our ancestors and their Jewish communities. This year, a breakthrough on a branch of my family tree in Prague led me to an amazing discovery of a long-forgotten family tradition that we’ll be celebrating again this year on December 30 (22 Tevet).

The Altschul family is one of the oldest families from Prague. They derive their name from the Old Synagogue, which was torn down in 1867 and replaced with the new Spanish Synagogue. The Old Synagogue in Prague was even older than the still-existing Altneuschul that was completed in 1270. In 1546, a list of Jews with letters of permission for residence in Prague includes my 10g-grandfather Enoch “von der alten Schule,” his wife Fredl and their five children Moses, Judka, Ryle, Sendl and Lida. Enoch’s son Moses became the author of Der Brandspiegel (The Burning/Magnifying Mirror), printed in 1602, which has been called “the first original comprehensive book of ethics in Yiddish.” Aimed primarily at instructing women who could not read Hebrew, the book included chapters on “how a woman should behave at home” and “how a woman should treat her domestic help.” Der Brandspiegel was an early Yiddish best-seller, going through numerous printings through 1706.

Moses Altschul’s son Chanoch Altschul (1564-1632), my 8g-grandfather, served for thirty years as a shammesh or servant of the Jewish community in Prague. In the winter of 1623, while the Court Jew Jacob Bassevi was away from Prague on business in Vienna, some fine damask curtains were stolen from the palace of Prince Charles of Lichtenstein. The capricious mayor of Prague Rudolf von Waldstein ordered an investigation and notified the public that the curtains were missing. In accordance with his official duties, Chanoch went to all of the synagogues in the Jewish quarter and made an announcement that anyone having information about the stolen curtains should inform him immediately.

No sooner had Chanoch returned home and settled down in his chair to study than the stolen curtains were dropped off at Chanoch’s home by Joseph Thein, who said he had purchased them unwittingly from two soldiers. Chanoch dutifully brought the curtains to the parnas or leader of the community Jacob Teomim, who turned them over to the mayor.

Waldstein was not satisfied merely to recover the curtains from Teomim. He wanted to know who had stolen them, so that he could mete out a severe punishment. Teomim said that he had received the curtains from Chanoch, but that Chanoch had promised not to reveal the name of the person who had brought them in. Waldstein ordered Chanoch arrested and brought before him with Teomim. Still, Chanoch refused to disclose who had delivered the curtains to him, saying that he could not violate his oath. Enraged, Waldstein ordered that Chanoch and Teomim should both be executed the following morning.

Chanoch saw that he had no choice, not for his own sake, but for Teomim he had to now disclose the name of Joseph Thein. He told Teomim the name of the man who had dropped off the curtains and freed him to disclose the name to Waldstein. This Teomim did, but Waldstein was not yet satisfied. He released Teomim but ordered him to bring Joseph Thein in by morning or else Chanoch would be executed and the community would be fined. Teomim consulted with Rabbi Isaiah Horowitz, known as the Sheloh, author of Shnei Luchot Habrit. Since there was no time to seek help from the Court Jew Bassevi, who was out of town, Horowitz advised Teomim to bring Joseph to Waldstein and hope for a miracle. When Teomim returned with Joseph, Waldstein ordered Josef arrested and put in jail with Chanoch. The next morning, Chanoch and Joseph were brought to Waldstein, who angrily released the elderly Chanoch but sentenced Joseph to be executed forthwith.

Chanoch returned back alone through the snowy streets to the community and told them what had happened. Hearing the news, Joseph Thein’s sister Mirl secretly approached her old friend Gadl Emmerich who had left the community, converted and become a priest. Gadl agreed to help by convincing Waldstein’s wife to implore her husband to commute Joseph’s sentence. Finally Waldstein relented and agreed to release Joseph Thein in exchanged for a large payment from the Jewish community. To add insult to the injury, Waldstein ordered his soldiers to escort ten leaders of the Jewish community dragging the payment of silver coins in bags through the wintery streets of Prague to the city hall.

In the end the convert Gadl approached Rabbi Horowitz, repented and returned to Judaism. To avoid capture, for converting back to Judaism was a capital offense, he faked his own death by dropping his coat in the river, and snuck off to Amsterdam, where he was later joined by Mirl. Jacob Teomim’s daughter Zipora married Ascher, the son of the Court Jew Bassevi. Rabbi Horowitz left for the holy land and died in Tiberias in 1630.

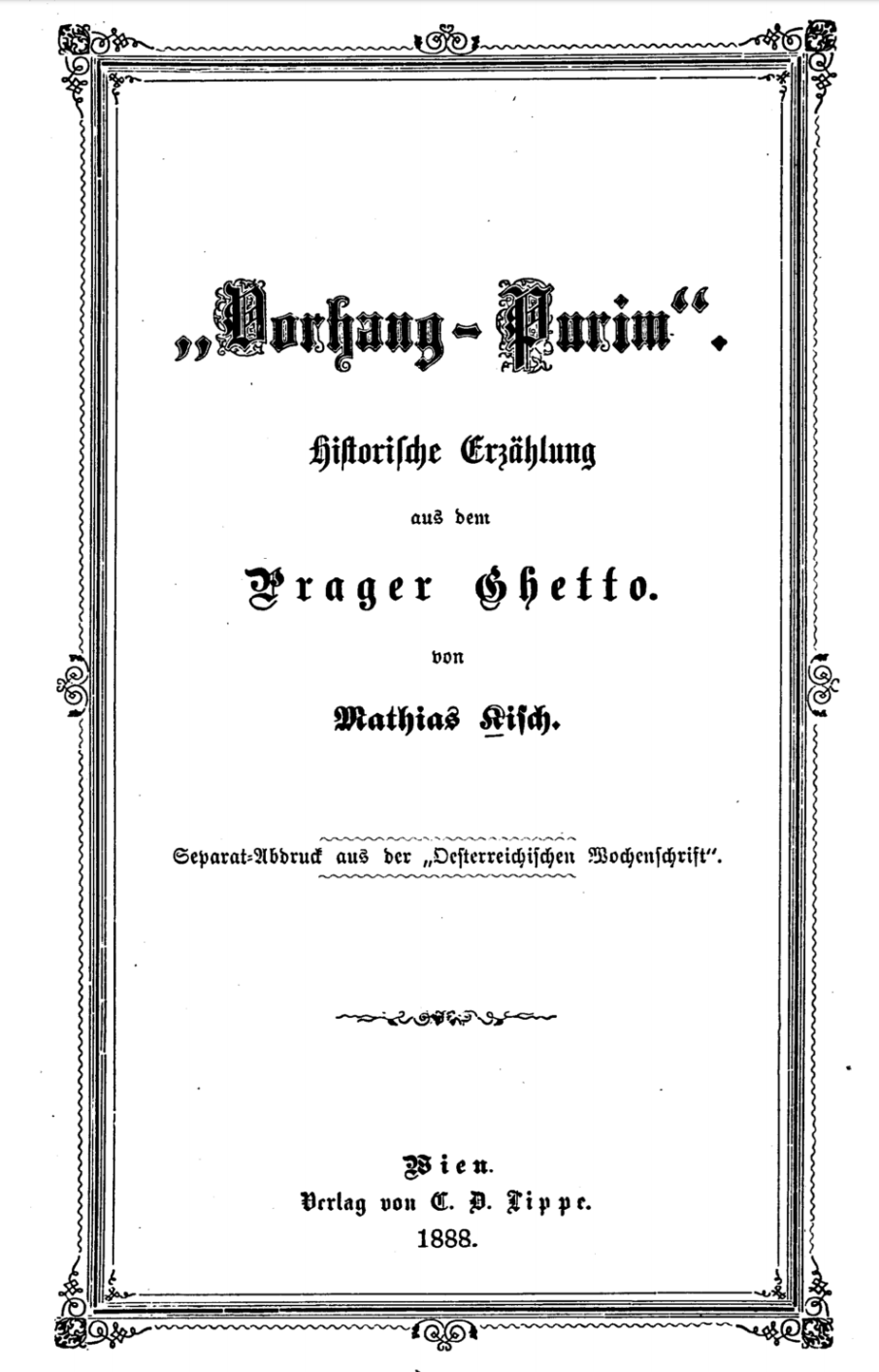

Before he died, the elderly Chanoch recorded this entire story in a megillah scroll that he commanded his descendants to read every year on 22 Tevet. The story was translated into German by Mathias Kisch in the late 19th century and was well known enough to be included under the title Purim Fürhang (Curtain Purim) in the Jewish Encyclopedia in 1906. Having re-discovered this old story, and the direct connection of my own family, I will be celebrating the Purim of the Curtains for the first time this year on December 30.

Purim of the Curtains (English)