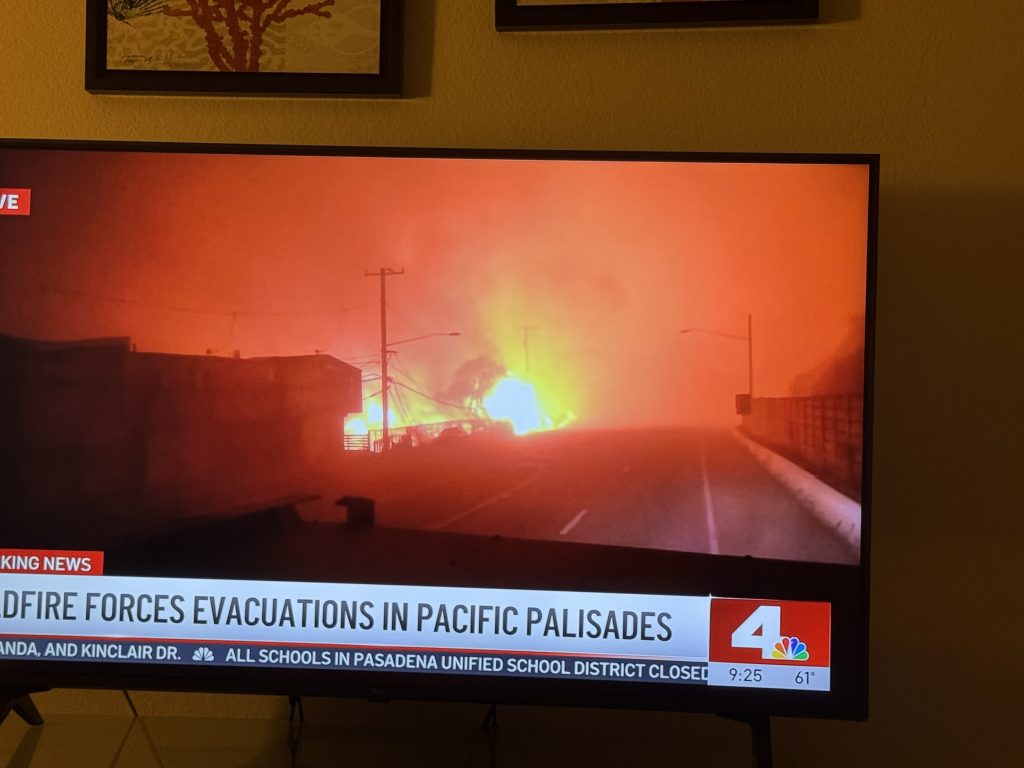

Our home in Malibu burned down on January 7, 2025. Already that evening I received a photo of the Channel 4 news showing our home as a ball of fire. It was several weeks before I could focus on the question of whether we would rebuild. In February, I asked a friend and neighbor who is a builder, and had lost a home he was building in the Palisades, to start designing and planning the new home.

But first, I needed to know whether we would receive our insurance money. On February 10, I received an email saying our claim was approved. We did not receive any funds until a small partial payment came on March 11. Further funds came on March 19. At that point, I was confident we would have the funds to rebuild, if we wanted to. We decided to pay our builder friend for the work he had done, and on March 21 we hired another friend who is an architect to manage our project.

As of that time, our lot and most of the Palisades and Malibu was still filled with debris. I had gone through weeks of stress getting the paperwork approved so that our lot could be cleared. Our first online submission disappeared. A second submission made in person at the recovery center on Pico also got lost. I sent an email follow-up and someone at LAPW found it and called me. I sent him again all of the paperwork, called him back repeatedly, but still no success. Finally, I submitted online again, and suddenly we got through the process, much later than most of the other victims. Nevertheless, or maybe because of these problems, we were among the very first to have our lot cleared, and on March 25 it was done.

On February 28 I retained a licensed surveyor I had used previously to do a new survey for our property. Getting down to Malibu at that time was not easy, and the surveyor needed the lot cleared. The surveyor didn’t get a preliminary survey done until April 22, and it had some issues that needed correction. Unfortunately, she refused to complete the work and, even though she promised to reverse the charges, I had to get them reversed by American Express. On June 25, we hired another surveyor and he completed the work on July 28. We still need some markers placed on the border (because the lot line is not easy to find and is not perpendicular to PCH), but that hasn’t been completed as of August 24. So, six months after hiring a surveyor we aren’t even finished with that process.

When I first visited the Malibu Rebuild Center on February 19, everyone was very friendly. I had emailed for an appointment and got a very quick invitation to come down. At that time, PCH and Topanga Canyon were both still closed, so the only way to get to Malibu from Brentwood was through the Valley, with a nice, but long, drive through Malibu Canyon. I met with several people, and Lauren Doyel gave me lots of advice, including that we’d have to remove our two septic tanks and replace them with a new advanced onsite wastewater treatment system surrounded by a very expensive new sea wall. The costs would likely be hundreds of thousands of dollars, and this before we even got to the foundation of the new home. At that time, we were still uncertain of our insurance recovery. I was questioning whether the funds would be sufficient to rebuild if we had to spend so much just to replace the septic tanks. Ultimately, I stopped trying to calculate whether it made economic sense to rebuild. There were too many moving parts (including a separate insurance payment we get only if we do in fact rebuild). When we hired our architect, I decided that we should rebuild even if we had to invest even more money in the house. That decision relieved lots of my stress and anxiety. I told people I had gone through various stages of grief and was finally at acceptance.

After Lauren Doyel’s advice that we would not be able to keep our old septic tanks, I decided to make sure. So when the lot was cleared, I immediately hired someone to inspect the tanks. The inspection came back and said the tanks were destroyed and needed to be removed. So I hired another company to remove them, using a recommendation of a local contractor from a neighborhood Whatsapp group I had joined on March 2 after one of our neighbors found me. I also needed this contractor to clear some debris that had fallen from our home onto the neighboring beach operated by the MRCA. On April 17, after finally getting permission from MRCA, the contractor sent people to clean the remaining debris and remove the septic tanks and we discovered that the initial inspector I had paid did not even visit the property before submitting a report saying the tanks were destroyed. The tanks were still buried. They dug them up. One was in good shape, and the other needed repairs. I decided to bite the bullet and have them both removed, following Lauren Doyel’s advice. There had already been discussions in Malibu about installing a sewer line, but I had no confidence that it would ever happen, and was sure that it wouldn’t be completed for many years, likely beyond the six year time frame to rebuild the house without interference from the coastal commission under the governor’s order. The initial time estimate announced at a Malibu town meeting was 65 months, and that did not include the time needed to give the green light on the project (i.e. all of the various council meetings, and presumably an election to approve a bond measure). The septic tanks were removed on April 28.

After a number of meetings with our architect, on June 6 they submitted plans for a preliminary review by Malibu Planning. We had to get notarized signatures on a form authorizing our architect to submit the plans. (Despite this, every official communication from Malibu Planning goes only to us, and not to our architect, so I have to catch the email and forward it to my architect. No idea why that is.) Our coastal pre-screen report from Lauren Doyel came back with comments on July 18 (42 days, if you’re counting). All of the notes were negligible, and there was one glaring error on their part where they for some reason thought we were rebuilding a duplex even though we had done a formal lot merger in 2007-8. We had a zoom meeting with Lauren on August 1. The plans were corrected and resubmitted on August 13. As of today (12 days), we haven’t received a response.

We’ve been proactive as we can be in trying to hire experts. On May 19 we hired a coastal engineer experienced with Malibu to do a wave uprush study, a necessary report for any rebuild on the beach. Our architect has been prodding her to finish, but despite many promises, we didn’t receive the 2-page preliminary wave uprush report until August 22, over three months later. The final report was supposed to be sent this weekend but I haven’t seen it. Our coastal engineer thought we might not need to build an expensive sea wall around our septic tanks if we can rebuild the rock revetment in front of our tract. On Friday she said that the plan for our septic tanks was “too far” back from the coastline and we might still need a sea wall, which makes no sense to me. The issue is that the septic must be as far as possible from the coast and because we now have a double-lot, our tank can be be wider than it was, and not as long, and therefore a few feet closer to PCH and away from the coastline than it was previously. Why we should be penalized for that, I have no idea. But in any case, it’s time to repair the rock revetment protecting our whole tract, with the hope that this will obviate the need for an expensive sea wall. That revetment repair will require coordination among all the neighbors. I have been doing research for some time, even went to the Coastal Commission offices in Ventura to scan old applications and maps from previous repairs of the revetment which took place in the early 2000s before we bought our home. I spoke with the contractor/expeditor who removed our septic tanks, and he wants to work on the project. He said that last time it took a full year to get the repairs done. I am hoping we can do it much faster this time, hopefully without the need to go to the Coastal Commission. Not sure why getting permission to put the big boulders back where they were before they fell down towards the ocean would be such an ordeal, but this is how things work (or don’t work) on the coast.

Another expert we hired is our soils engineer. We hired them on May 15, based on their estimate of two weeks for excavations and another six weeks for a report. They did not visit the lot until June 23 (five weeks), and then realized that they could not get their boring drill onto the property because of the telephone lines. All but one of the houses in our tract had been cleared but they needed the last one cleared in order to get to our lot from the other side. That lot was cleared a few days later on June 26, but the drilling company did not return until July 9 when they successfully drilled two holes in the soil down to the bedrock. The full report arrived August 21, over three months from when we hired them.

The wave uprush study and soils report are necessary before our septic engineer can plan the new septic tanks, and the structural engineers can begin working on a plan for the foundation and support of the new home. Now that we finally have those in hand, they can begin work. So that’s where we are at the moment. If we have to wait for the revetment repair before the plans can be finalized this may delay our entire project for a long time. Getting all of the neighbors in our tract to sign off on the revetment repair is going to be a chore. Several of them are working on their rebuild, but another bunch are stuck. Some have land leases, which puts them in a similar position to mobile home residents. The property ownership is divided and so it doesn’t necessarily make economic sense for the home owner/tenant to spend his insurance money on a new home that he won’t end up owning at the end of the lease. The long-term lease is now a liability, not an asset, as they are required to pay rent for an empty lot that cannot be used. So these people are stuck in limbo. But in our tract, we’re tied together with our common walkways and rock revetment. So we need their cooperation. It’s going to be a struggle.

On my initial trips to the rebuild center I tried to get a handle on some of the issues that I could foresee. The people there were always very nice, but often I could not get definitive answers. Basically, each of the six sides of the box that is our lot has an issue. The easiest side is actually the beach side, where there is a string-line rule that says we need to rebuild our deck in exactly the same spot. On the east border with the beach operated by MRCA, beyond the issue of finding the corner and drawing the non-perpendicular line out from PCH, we have to calculate where we can build our stairs, which may have to be different from what we had before because of the new concrete pylons replacing our wood ones and new code rules on staircases. The access onto the beach over some of the boulders is also a bit tricky (there were some steps there on the MRCA side of the property but those see to have been removed during the debris removal, and MRCA isn’t easy to deal with, to say the least — see my old blog about correcting their disastrous beach renovation project). On the north border with PCH there is the fact that the retaining wall for PCH has issues and needs to be repaired. On the west border, we (like all the others in our tract) had a narrow walkway between our garage and our neighbor’s garage, not to current code. I took several trips down to the rebuild center before speaking to the fire department and getting a verbal confirmation that we could build with the same narrow width (4 foot total, 2 on our side and 2 on the neighbor’s side), which is far less than the ordinary 10% setback would be for our lot, now that it is combined and is 43 feet wide. I hope that remains true after we submit plans. Building out the common walkway, with an easement onto our neighbor’s property, will require cooperation with the neighbor. But he has been mostly incommunicado and has said he might not rebuild. How can we build a common walkway and stairs if the neighbor won’t agree? The rebuild center didn’t have an answer for that. I said six sides because we also need to know the top and bottom. We can build up to 110% of the prior height. How tall was our home? No one seems to know and none of our old plans has that dimension. The limit is 24 feet for a flat roof and 28 for a pitched roof in Malibu. Can we build up to 24 feet? Who knows? I asked about whether we could have a roof deck, since one of our neighbors in the tract did have one. No good answers. It’s complicated, even though there are no view issues since there’s a huge mountain hillside going way up to the Big Rock area on the other side of PCH. And then there is the bottom. We need to be above the FEMA limit which is 19 feet elevation in our area. Our house was at 21 feet so we should be good. Then our coastal engineer said she thought we might need to a bit higher than 21 feet because of the wave uprush study. More complicated. If you need to raise the house up because of FEMA you can do that, and not lose height, but they don’t have a rule that allows you to raise the level because of the wave uprush study. Turns out now the coastal engineer thinks we might not need to raise the level after all. But, not easy to build a house on a small lot if every single dimension is uncertain. And did I mention that we didn’t even know how wide our property was? It’s shaped like a parallelogram, but until we had the survey finished we weren’t sure about the angles and couldn’t calculate the width between the east and west boundaries. Fun, fun fun.

One other issue to mention, there’s a new program to refund building fees for Malibu residents. Apparently we don’t qualify because it was our second home. When another person in the same boat asked why, the response was that it was to make sure developers paid fees. But there are a bunch of us who are not developers, just part-time residents. I sympathize with the need for Malibu to collect fees to cover all the expenses of running the rebuild center, so I’m not too upset. But I don’t like being lumped in with speculators and developers when they try to justify the discrimination against non-residents. We never even rented our home, so Malibu’s been getting a pretty good deal from us, lots of taxes paid and very little demand on services.

So those are the issues at the moment, at least the ones I am focused on. How long will the rebuild take? It’s anyone’s guess at this stage. How much will it cost? Again, no idea. This isn’t how you normally build a home. We build our home in Brentwood Glen in 2004-5 and it took about 18 months. This time won’t be as easy.