Sep 30, 2013

I am heading off to the Czech Republic with my 13-year-old son Nathan to attend the rededication of an old synagogue in Ckyne, southern Bohemia. Our first stop is Prague, the capital city where my great-grandmother Pauline Nachod was born in 1848.

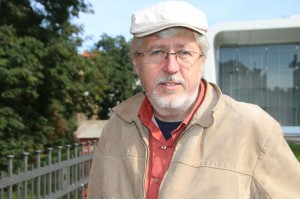

I have been to Prague before. The first time was when I was a teenager, during the Communist era. At that time, getting a visa to enter the country was difficult and tours were very constrained. Interaction with ordinary Czechs was pretty much out of the question. I returned to Prague in 1991, after taking the bar exam. Following a brief lunch with my aunt Nuria’s friend, the musicologist Ivan Vojtech, I tried to track down a cousin of my paternal grandmother Gertrud Kolisch. I looked in the café’s old telephone book that had not been updated in twenty years and found Dr. Rudolf Kolisch. So I called the number. The young man who answered (I later learned he was just 15) did not speak English, nor French, but uttered a few words in German before hanging up on me. “My grandfather is dead. My mother is not here.”

Traveling alone and having nothing better to do, I took the address in the old phone book and decided to try to see if I could find my cousins. I took the bus to the outskirts of town, to a residential park filled with 10-story apartment buildings. When I finally found the building matching the address I scanned the intercom directory. No Kolisch. My grandfather is dead, the boy had told me. His mother wasn’t home. So the apartment must be listed under the mother’s married name.

Well, I had come this far. Undeterred, I went over to the sandbox playground next to the building. Some young folks about my age (25) were playing with their babies in the sandbox. I asked if they spoke English. No luck. French? No. German? No again. One of them spoke a little Russian, but my four weeks of Russian in seventh grade didn’t get me very far. So I took out a little notebook and drew a picture of my family tree, up through my father to his mother and her father, then sideways over to his brother down to his son and then to ?, the woman in the building. They understood enough and ran to get the help of an old lady in a nearby building. She spoke German with me and told me she would call my cousin. In a little while I was ushered into the building and introduced to my cousin’s neighbor, with whom I conversed for nearly an hour in French. Who knew I could even speak French? I thought I had forgotten it all.

Finally, my cousin Michaela Navratilova walked through the door. I don’t remember my grandmother, who died when I was just a baby, but from the photos I knew I could recognize that Michaela had the same face. No doubt she was a Kolisch. With tears in her eyes, we embraced. She had known of our existence, but had never communicated with us. Her father and brother had died over a decade earlier, and she felt herself completely cut off. With only her father’s books to remind her of the more cosmopolitan world before 1939, she had until the fall of communism in 1989 never seriously allowed herself to dream of traveling abroad or of meeting another member of her father’s family. And now here I was, opening the door for her to the outside world.

Michaela took care of me for the next several days, showed me the little cabin in the woods that her husband had built with the plum tree laden with fruit. We went hunting for mushrooms. At each one, she said “Hmm. I’ve never seen one like this before.” On the way back to the cabin, we stopped at the local gas station and she asked the woman who lived upstairs to come down and inspect our basket of mushrooms. Returning to the car with a smile, she assured me the old woman said they were all non-poisonous and edible. Not completely convinced, I let her son Tomas, the one who had answered my initial phone call, taste the stew first. When he didn’t drop dead, I ventured a taste and then dug in. For dessert, we ate dozens of homemade plum dumplings called Zwetschkenknödel in German.

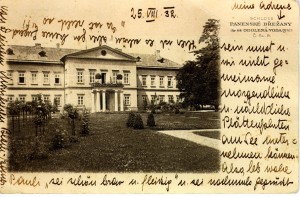

I returned to Prague in 1996. Pam and I had just become engaged and she joined me on a trip to Vienna for a family reunion I had organized with the various branches of my family. Beforehand, I had planned a side trip through Moravia and Bohemia to visit the towns where my ancestors had lived. The plane landed in Vienna after a long flight and we immediately set off into Moravia in a rental car. Many hours later, we arrived at Kromeric, exhausted, and found a hotel. Waking up the next morning, eager to explore, we looked for our car. And looked. And looked. It was gone, taken during the night. The hotel claimed that the parking lot out front was not its responsibility, which was small comfort. I had been too tired to put the “club” on the wheel and bring the last bag up, the one with Pam’s dresses, to our room. She still hasn’t forgiven me for losing them.

After touring the bishop’s palace in Kromeric, we decided to go directly to Prague and boarded a train in nearby Holesov (birthplace of my great-grandfather Hermann Jellinek). The train stopped on the way in Pardubice (birth-place of my great-great grandmother Rosalie Reichmann). As we had no food or drink, I decided to get off the train while we are stopped at the station and buy something to drink at a small stand. I handed the woman a large bill, the only one I had, and she mumbled something in Czech and ran off to make change. As I waited for her to return, the whistle blew for the train to depart. I grabbed the change from the lady and ran for the train, just hopping on as the train gained speed and headed out of the station. By the time I got to our cabin and found Pam, the train was at full speed, and Pam was white as a sheet. Day one of the trip: car stolen, dresses stolen, and now alone on a train, not even certain where she was going. She thought I had abandoned her! Our stay in Prague was clouded by the difficulties of our first day. It took two days, until we arrived in Vienna, before Pam smiled again.

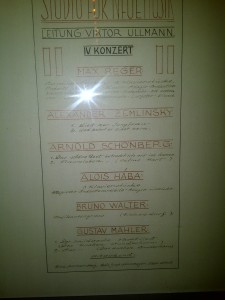

After the family reunion and a trip to Salzburg for a performance of Moses und Aron, Pam returned home and I went back to Prague alone, staying in the apartment of my cousin Nick Teller. Nick had been raised in England and Germany. His father was my grandmother’s cousin and his mother was from Prague, a survivor of Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Nick worked at the German Commerzbank in Prague, almost as a quadruple-agent. He could play British, Czech, German or Jewish and witnessed the worst prejudices of all these groups in Prague. I used my stay to visit the Czech State Archives and get copies of records of my family. These records had been maintained by Jewish communities in Bohemia and Moravia since 1782, when the Habsburg Emperor Josef II issued his famous Tolerance Patent, granting Jews some civil rights. (They would not be fully emancipated until after 1867.)

The records had been collected during World War II, as the Jewish communities were liquidated by the Nazis, and ultimately were deposited in the Czech State Archives. One of the books I found was for the small town of Ckyne in southern Bohemia. All I knew of the town was that Rosa Bloch, the maternal grandmother of my grandfather Eric Zeisl, was born there. She was apparently a nasty lady, who burned my grandfather’s early compositions and criticized him for “playing instead of practicing.” My grandfather half-joked that he had three enemies in his life: Hitler, the sun and his grandmother. That he would put her in the same category as Hitler gives you some idea of what she must have been like.

Anyway, I found the old record books from Ckyne in the Czech State Archives. Probably no one had looked at them for decades. I traced back from Rosa to her father Isak and then to his father Mathes Bloch. I soon noticed that Mathes Bloch had signed as the mohel for all the boys born in the town in the first half of the 19th century. The whole book was in his handwriting. I triumphantly reported back to my family that we were descended from the Mohel of Ckyne. Only years later, when the cemetery was photographed, did I learn that Mathes (or Mendel) Bloch was in fact not only the mohel, but the rabbi of Ckyne.

Several years later, I received a call out of the blue from a man in Boston named Alex Woodle. He said that he just learned that his family, who came over to the US in the 1840s, may have come from Ckyne. I pulled out the copies I had made of the pages where the Blochs were mentioned in the old record book, and sure enough, right next to them were the records for the Wudl family. Alex was thrilled to get confirmation and help tracing his family back another generation. Ultimately, he went to Prague and Ckyne and even made a film about his discovery that was shown on TV.

I kept in touch with Alex and over time we discovered a number of other families that descended from the Jews of Ckyne. Amazingly, many of these families also had avid genealogists. Emily Rose even published a successful book on her family. Rochester professor Phil Lederer put up a detailed account of his roots trip to Ckyne on his website. So did Francisco Fantes. Heleen Sittig in the Netherlands had an entire website devoted to her family tree.

A few years ago, Alex announced to me that a woman named Jindra Bromova in Ckyne had arranged for the town to repurchase the old synagogue building and restore it. She managed to raise over 200,000 Euro from the European Union and intended to turn the building into a Jewish cultural history museum of southern Bohemia. Apparently, this synagogue, built in 1828, was the finest example of synagogue architecture left in the entire region.

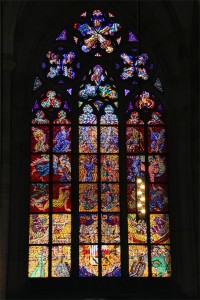

The Czech Republic was not bombed very much in World War II and so many of the synagogue buildings, including the very old and beautiful ones in Prague, still stand. The Ckyne synagogue had been abandoned as Jews moved to larger towns and was sold even before the Nazi era. From what I have seen, it is a large, rather ordinary looking building. But the inside has been nicely restored and so I am curious to see what becomes of it. When Jindra wrote to tell me that there would be a rededication ceremony, I decided I wanted to be there.

As it happens, the rededication is on October 6, just six weeks after our son Nathan’s bar mitzvah. Pam and I decided it would make sense to pull him out of school for a week so that he could attend and participate in the ceremony, as the representative of his ggggg-grandfather Rabbi Bloch.

So we are off to Prague. Michaela will be meeting us and she and our cousin Petr Wilheim will take us to Theresienstadt on Wednesday. I have never been to a concentration camp before. When I admitted this to a group of Holocaust survivors a few years ago, I was berated and told I must go. I have misgivings. First, I am not someone who needs to go somewhere in order to be reminded of the Holocaust. As the President, and for the past ten months Acting Executive Director, of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, I have to deal with the memory of the Holocaust nearly every day. I also don’t feel any special connection to the main camps. My great-grandfather Sigmund Zeisl was deported to Theresienstadt in July 1942 and deported two months later to Treblinka, where he was presumably murdered on arrival, if he even survived the train ordeal. There is nothing at Treblinka for me. Just a monument at the place where he was taken for execution by his kidnappers. If I wanted to connect with my great-grandfather, I would go to Vienna, where he lived for ll but the last two months of his 70-year existence.

Of course, I have read a great number of books about Theresienstadt. My great-grandfather’s time there was no doubt brief and terrible. The elderly did not receive enough food to survive for long and the crowded and diseased living conditions made the mortality rate astronomically high, even in this supposedly model ghetto. Theresienstadt was a garrison town, built to house soldiers, and what remains are the same barracks and buildings. Now they house museum exhibits about the infamous Nazi ghetto. I am at the same time eager to see how the Museum deals with the subject-matter and at the same time afraid of the emotions my trip there will be sure to evoke. I am not sure how traveling with my son will affect me. Just thinking about it makes me well up with sorrow and indignity and terror at the inhuman cruelty of it all. Being there will not be easy for me, which is why I have avoided it until now.