October 2, 2013

Michaela picked us up at the hotel to drive us to Theresienstadt. She brought her late brother’s wife Hana with her. And we joined with our cousin Petr Willheim on the way there. Petr knew Theresienstadt well and would be our guide. His parents had both survived the camp, and he had even been stationed there when he was a young soldier. From the parking lot Petr took us first toward the Small Fortress. We passed a long rom of gravestones, mostly from late 1945, around the time of liberation, when thousands died of a Typhus epidemic that spread through the ghetto and the outlying areas. Half of the graves were Christian and half Jewish. Most of the Jewish ones had no names, just a number. Michaela said that she heard that Gypsies had stolen the iron names form the graves, but I later heard that the unnamed graves simply represented hundreds of unidentified people who died during the epidemic.

I wasn’t really much interested in seeing the Small Fortress. It has a few claims to fame, as the home of the SS men who administered Theresienstadt Ghetto, as the place where prisoners were taken by the SS to be tortured to death or executed, and as the place where Gavrilo Princip, the Serbian nationalist who started World War One by assassinating the heir to the Habsburg throne, was imprisoned. I asked Petr to allow us to turn back instead to the town where the ghetto had been.

We walked toward the old garrison town, with its star-shaped exterior walls along the river Oh?e (Eger). First we went to the memorial site where in 1944 the ashes of 22,000 prisoners who had died in the camp were thrown into the river. The memorial did not do much for me, a tall sculpture of a woman standing next to a marble block. Nathan and Petr waled down to the riverbank but I wanted to head back to enter the camp.

Despite having read extensively about Theresienstadt, I suppose I did not have a good mental picture of it. Once inside the walls, it appeared very much like an ordinary town, a bit shabby in places, but in many ways just fine, with open spaces, parks, and nicely painted buildings, not like the army barrack housing I had imagined. I took two pictures, to show how different you can make the place look, depending on where you point your camera.

We went into two buildings with museum exhibits. The first one was a comprehensive exhibit with the history of the Jewish camp, with text panels in Czech, German, English and Hebrew, and reproductions of many documents. I found the placards advertising concerts and events very interesting. Some of the things I had seen before, but I could have spent longer. There were some good videos also on display, in Czech with subtitles in English and German. But near the end I joined a tour being led by 92-year-old survivor Pavel Stransky. I only heard the last part of his story, and also an epilogue about the fate of Fredy Hirsch, a man who devoted himself to the care of children at Theresienstadt and later at Auschwitz-Birkenau. I had an opportunity, but did not feel like interrupting the end of the tour to speak with Mr. Stransky. After he spoke was the only time I felt that emotional wave of sadness come over me that I had been dreading on this visit. I wrote in the guest book: “First family member to return to Theresienstadt since my great-grandfather Sigmund Zeisl was here July-August 1942.”

Downstairs in the gift shop I bought a book on Vedem, the children’s newspaper in Theresienstadt edited by Petr Ginz. When I was in Prague in 1996, Michaela had introduced me to Martin Glas, who was a friend of hers. I have a video of our conversation where he showed me an issue of Kamarat, another magazine he had helped publish as a teen in Theresienstadt. He survived and later became been a tv news anchor in Prague. Downstairs there was also an exhibit room that had the names of all the children who who perished. At first I did not realize it was just children and spent some time looking for my grandfather’s cousin Arthur Schönberg, who died in Theresienstadt. But there were no Schoenbergs. Then we realized that they were only the children. It was overwhelming and sad.

We walked down the nice street to the Magdeburg Kaserne, the barracks that also housed the offices of the camp leadership. Upstairs was a good exhibit that included a few rooms made up like barracks, with triple bunks. I had presumed that suitcases had been taken from the prisoners, but I was wrong, and saw confirmation also in photos. Perhaps it was just the contents that were stolen. And maybe they were used then communally and not individually. I don’t know. Anyway, it was good to get a mental image of the barracks, even though it felt not quite as dingy and dirty as I had imagined it, probably because it was in fact clean and empty and not filled with sick and dying people, as it would have been when Theresienstadt was packed with ten times the ordinary number of inhabitants. The smell was missing. This is also Daniel Mendelssohn’s critique of the boxcars that pepper our Holocaust museums. Yes, they can give people a feeling of claustrophobia, but the stench, the cold, the heat, the fear — those are all absent.

We walked down the nice street to the Magdeburg Kaserne, the barracks that also housed the offices of the camp leadership. Upstairs was a good exhibit that included a few rooms made up like barracks, with triple bunks. I had presumed that suitcases had been taken from the prisoners, but I was wrong, and saw confirmation also in photos. Perhaps it was just the contents that were stolen. And maybe they were used then communally and not individually. I don’t know. Anyway, it was good to get a mental image of the barracks, even though it felt not quite as dingy and dirty as I had imagined it, probably because it was in fact clean and empty and not filled with sick and dying people, as it would have been when Theresienstadt was packed with ten times the ordinary number of inhabitants. The smell was missing. This is also Daniel Mendelssohn’s critique of the boxcars that pepper our Holocaust museums. Yes, they can give people a feeling of claustrophobia, but the stench, the cold, the heat, the fear — those are all absent.

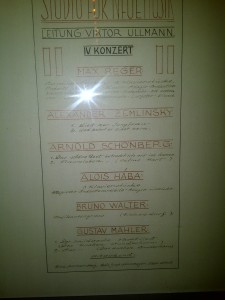

The exhibition included rooms on the artists, composers, writers and actors in Theresienstadt. I was surprised to see a placard for a concert put on by Viktor Ullmann that included two songs by my grandfather. Alice Sommer-Herz, now nearing her 110th birthday, was the pianist.

The exhibition included rooms on the artists, composers, writers and actors in Theresienstadt. I was surprised to see a placard for a concert put on by Viktor Ullmann that included two songs by my grandfather. Alice Sommer-Herz, now nearing her 110th birthday, was the pianist.

I did not feel like visiting the Crematorium and so we left Theresienstadt. It was an odd visit. I was used to our museum, where the architecture is part of the story. In Theresienstadt, the architecture worked against the story. These were just nice buildings in the Bohemian countryside. The exhibits were adequate, but not extraordinary. There was nothing there to give you the feeling that you were in the presence of a catastrophe, the site where tens of thousands of Jews were crowded together and murdered with hunger and sickness or deported to Auschwitz and Treblinka. The town is just a somewhat humdrum old country town, nothing more.

We went to nearby Litomerice for lunch. It has a beautiful town square, all neatly restored, and nice restaurants. No goulasch on the menu so I ordered duck with knödel on the side, which was Bohemian enough and very good.

We returned to Prague and visited my distant cousin Helena Vankova (Kovanicova), whom I had never met. We had corresponded over our Nachod ancestors for a number of years so I was eager to meet her.  She greeted us with her mother and two small children, Leah and Adam. Later her father Jiri, a photographer, came, as did her husband Daniel, who teaches and works for the Jewish Community in Prague. We had a nice dinner, speaking mostly English with some German.

She greeted us with her mother and two small children, Leah and Adam. Later her father Jiri, a photographer, came, as did her husband Daniel, who teaches and works for the Jewish Community in Prague. We had a nice dinner, speaking mostly English with some German.

They tried to teach us a few words in Czech, but I am afraid my brain can’t hold it in. It was nice to finally meet Helena, although she was so busy with dinner, I hardly got to speak with her. Her husband is friends with some folks I hope to meet later in the week, so it was nice to get to know him as well. He let Nathan try out his shofar, which was challenging.

We returned home for some computer time and now it’s time for bed. Tomorrow I hope to see some of the Jewish Museum and also maybe the Castle.