I’m always surprised when I find good genealogists who are not working on Geni.com‘s World Family Tree, the largest collaborative tree in existence, which will hit 100 million connected profiles in the next few weeks. I’ve written previously with Answers to Geni Skeptics, but I’d like to approach the problem from a different perspective. Below are the reasons why you really should be building your tree on Geni, and advising others to do the same.

Because a lot of the problem is a matter of reputation, first let me explain (in excruciating detail) why you should trust me on this issue. I recount this history, not to brag or bore everyone, but to demonstrate that I really do know what I am saying when I talk about Geni’s World Family Tree. When you weigh my comments below against others you might read or hear, keep in mind the source. Or if you trust me already, just skip to the numbered list below.

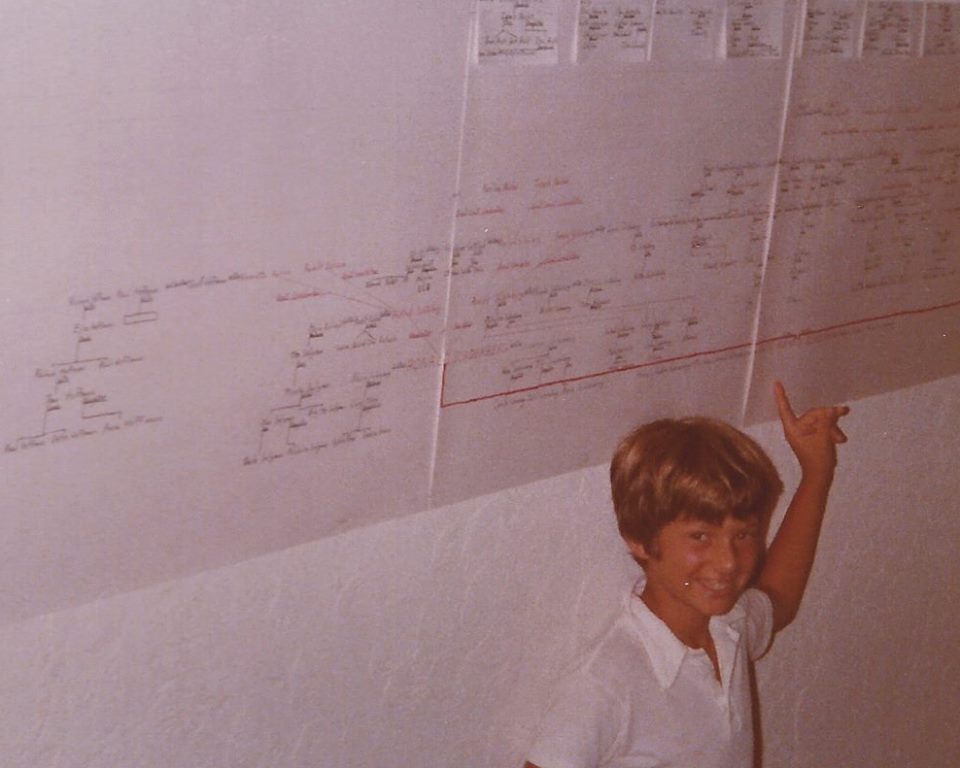

I have been an avid genealogist and computer enthusiast since I was in elementary school in the 1970s, which makes me perhaps uniquely qualified to advise people on how to use computers for genealogy. Here’s a picture of me in front of my 12-foot family tree in 1977, about the time I turned 11.

Around the same time, my uncle Larry introduced me to computers. If you don’t understand what it means to program Mugwumps in BASIC on a Commodore Pet, you probably haven’t used computers as long as I have.

I continued to be the family genealogist and computer maven through high school and college. At Princeton I majored in Mathematics and received a certificate in European Cultural Studies. Of course, I also took courses in Computer Science at Princeton, and also during my semester abroad at the Free University of Berlin in 1987. One of my deans at Princeton, Patsy Cole, turned out to be my third cousin once removed (a fact I discovered because I knew the names of all sixteen of my great-great grandparents).

I returned home to Los Angeles for law school at USC, and during the next decade took advantage of the library at UCLA and our nearby Family History Center, where I spent days underground combing through microfilms of records from Austria and Hungary. Over the years, I have also done archival research on-site in Vienna and Prague. I am pretty comfortable with library and archival research, having done a ton of it as a high school debater, including summer camps at Redlands and Georgetown. I also interned in my grandfather Arnold Schoenberg’s archives when they were at USC in 1985, and helped my aunt Nuria when she was working on her document biography, Arnold Schonberg, 1874-1951: Lebensgeschichte in Begegnungen.

Because I have always been an Apple/Mac person, I used an early version of Reunion for Mac to computerize my family tree. By 1996, I had managed to put my tree on the Internet using a program called Sparrowhawk by Bradley Mohr that converted GEDCOM files to html. This may not sound like a big deal today, but remember that in 1996 newspapers like Los Angeles Times and New York Times were only beginning to launch their online versions.

I attended my first IAJGS conference in 1998, and helped form the Austria-Czech Special Interest Group on JewishGen, which now has 1,800 members. On our website you can find my two articles: Beginner’s Guide to Austrian-Jewish Genealogy and Getting Started With Czech-Jewish Genealogy. Over the years, I have become increasingly more involved in Jewish Genealogy, and have attended the past six IAJGS conferences, giving lectures on a variety of topics, including Geni. I serve on the advisory board of JewishGen, the main Internet hub for Jewish genealogy. I also founded the Jewish Genealogy Portal, by far the largest Jewish genealogy group on Facebook with about 15,000 members.

After giving the keynote speech about the Recovery of the Klimt Paintings at the 2008 IAJGS conference in Chicago, I met Noah Tutak in the vendor room where he was advertising Geni.com, then a relatively new online family tree program. Geni was started up in 2007 by David O. Sacks, the former CFO of PayPal, and in May and July 2008 Geni had announced both GEDCOM importing and Tree Merging, two features that allowed for explosive growth and the creation of a World Family Tree. I was intrigued with the idea of an online tree-building program but did not act right away. That fall, I weighed options for moving my tree to a different platform. Because I had incorporated enormous GEDCOM files given to me by David Solomon for the Gomperz, Wertheimer, Oppenheimer, Fraenkel, and Chalfon families, my tree (at that time kept on Reunion) included about 54,000 profiles. I’d guess only about 5% was my own work. By placing it on the Internet, I had attracted lots of attention, some from people angrily accusing me of “stealing” their work (apparently unclear on the concept that genealogical facts are public domain), but more often from people who were happy to find so much of their family tree online. Keeping the tree updated with new information and corrections was beginning to be a chore. A more collaborative site seemed to be the perfect solution.

In February 2009 I began uploading my tree to Geni.com. I had to break it into parts, because the GEDCOM upload feature had a limit of 50,000. Because I didn’t know that (at the time) the search index feature had a lag of several days, I thought it did not work and tried to upload it a second time. This caused a big headache, and there are still remnants of this mistake on Geni, although most of the second upload has been deleted or merged to eliminate the duplicates. I didn’t realize at the time that my GEDCOM upload was one of the largest that Geni had ever had. At the time, the World Family Tree on Geni had just 8 million profiles, but was growing at the rate of 2 million per month. The tree I contributed — again mainly compiled by David Solomon (to whom I always try to give credit) from published sources, such as Louis and Henry Fraenkel’s Genealogical Tables of Jewish Families, 14th – 20th Centuries and Neil Rosenstein’s The Unbroken Chain — became the backbone of the Jewish tree on Geni. David wasn’t happy to see all his work on Geni, but the decision to move it there was the right one, as history has proven. The tree has grown and improved many times over since then.

At first, working on Geni was difficult for me even though I was technically and genealogically very proficient. There were forums where you could complain or ask for help, but the learning curve was steep and some of the ways Geni worked just didn’t seem to make sense. But eventually things improved and I got used to the way Geni operated. After two years, in 2011 I was made a volunteer curator on Geni, and this gave me much greater insight into how the program works, and what its strengths and weaknesses were. I even visited Geni’s old offices in Beverly Hills a few times where I showed them how I used the program (and they taught me some of its unadvertised tricks). Geni was purchased in late 2012 by MyHeritage and since then there have been a number of new features, most notably the ability to add references and sources on Geni profiles with links to records and trees on MyHeritage.

In the 7 years I have been on Geni, I have tried to build upon the work that I imported via GEDCOM. I have added another 85,000 profiles to the tree, much of it from original research using online records from the Czech State Archives in Prague, and now manage about 140,000 profiles on Geni. I like inviting people to Geni when I work on their tree, and have invited over 1,300 people so far. There are a number of ways to add sources on Geni, and I like to add screenshots of documents as profile photos. So far, I have added over 21,000 of them. I work pretty much every day on Geni, and have set up a number of large projects there, including the Jewish Genealogy Portal, Jewish Celebrity Birthday Calendar, Geni Top 10 Lists, Holocaust: The Final Solution, Jewish Communities in Bohemia and Moravia, Prominent Jewish Families of Vienna, Tolerated Jews of Vienna, Jewish Families from Prague, and Jewish Families from Frankfurt. There are many features that still need improvement on Geni, as with any program or platform, but that’s a topic for another day. If you want to read about some of the history of Geni, some of the curators have put together a history of the World Family Tree. Ok, so now for the reasons you absolutely need to be building your tree on Geni.com:

1. Working collaboratively is better than working alone. Think of it this way. Who can accomplish more: (a) you alone or (b) you working with me? Sure, it’s a fun challenge to do an entire jigsaw puzzle by yourself. But it’s even more fun to do a larger puzzle with a group of friends. And let’s face it, your family tree is an enormous puzzle. How big is it? Well, let me give you some idea. I developed a program called the Geni Forest Density Calculator, to measure how many people are within n steps of a profile (where each parent, sibling, spouse or child is one step away). If your tree were filled out completely (everyone has all of his/her parents, siblings, spouses and children), how many people would be within just 6 steps of you? For some of the historical figures we’ve tested, like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the number is about 13,000. Of course the largest figures are for the folks with many wives, like Brigham Young, who has 70,943 people within just six steps. At 10 steps, he has 1,153,592. So, good luck with that if you are working alone. There really is no other way to have a remotely complete or comprehensive tree than to collaborate and work with others, and Geni has the best platform for that type of collaboration.

2. “I don’t care” is not a valid genealogical principle. I used to think I had enough problems with my blood relatives, and didn’t need to worry about filling out the trees of all the in-laws. Big mistake. Sometimes the best way to make progress is by “going sideways” into the trees of people who married into the family. After all, who attended your great-uncle’s wedding? Not just his side of the family; but also his wife’s. All those people you think of as non-relatives could be holding clues to your own family — photos, documents, stories and more. Taking a broad view becomes more important the further back you go. When you get back to your ancestral village with a few hundred people in it, you can pretty much be assured that everyone in town is related to everyone else — by blood, marriage and everything else. These folks often lived in the same place for hundreds of years, meaning that over time all of the families braided together into one single family. If you aren’t working together with everyone researching that town, you’re making a big mistake. Where else but Geni can you collaborate with others and build trees for an entire town?

3. Preserve your work for the future. Most people start genealogy with a pretty narcissistic it’s-all-about-me approach. Just look up top at that picture of me from 1977, pointing to myself in the center of that large tree. But as you mature, you should start to think about how you can contribute your work to something larger than yourself. You want to pass it on to your family, to posterity. The best way to do that is not to work alone. That tree on your hard drive has no chance of ever being found or used by anyone. It’s gone as soon as you are. Same with all those files in the garage. Even if you self-publish a book, it’s unlikely to ever see the light of day again. No, the best chance you have of making your work last into the future is by contributing it to the World Family Tree. At 100 million connected profiles, Geni’s World Family Tree is by far the largest and fastest-growing tree in existence. To give you an idea, it is 10 times larger than its nearest competitor WikiTree. Geni’s annual growth in the World Family Tree is about 7 million per year. You want to be part of that growth. Because in the end, the World Family Tree on Geni is a unique and relatively valuable asset. Whatever happens to Geni or its parent company MyHeritage, that asset isn’t going to go away. No one is going to want to start over and repeat all the work that went into creating it. So, as long as people are interested in genealogy, people are going to want to have access to this tree. It’s going to be around in some form or other for the rest of recorded history. That’s right, forever. Of course, the same might be said for copies of your tree that you put on Ancestry or any other platform. But Geni’s World Family Tree is something different. It is a living tree, improving daily with millions of people working collaboratively on it. As people quit and die off, all those small trees on Ancestry will just stagnate, frozen in time. They’re like tiny, incomplete snapshots of small twigs on the big tree. They are nice to keep around in the drawer, but when people want to look for something, they’re going to look first to the big, living tree.

4. Let’s face it, you’re lazy. I know why you haven’t put your tree on Geni. You think it’s a lot of work, and you don’t want to have to redo everything you’ve done for the past umpteen years. Sure, back when I joined in 2009 all you had to do was upload your GEDCOM and you were there. But that feature was discontinued because it caused too much duplication. On Geni, each person gets just one profile on the World Family Tree, so any duplicates have to be merged. If GEDCOM imports were allowed, it would be a nightmare, because everyone would be importing huge trees duplicating what is already there. Anyway, the good news is that pretty much everything you have on your GEDCOM is already on Geni. What I mean by that is that with few exceptions you cannot find a large family tree with more than a few hundred profiles that is not already mostly on the World Family Tree. Nearly two-thirds of all of the profiles on Geni are already connected to the World Family Tree and the largest unconnected trees are all mostly fewer than 1,000 profiles. All of the easy, available large trees have already been added to the World Family Tree. So you’re well-advised to just start your tree by hand and build up until you get a match to the World Family Tree and can merge in. If you are a paying Pro user, you can also use the amazing tool SmartCopy, a Google Chrome app developed by Geni curator Jeff Gentes, that allows you to quickly import one family at a time from a whole host of platforms, including Ancestry, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeMaker, RootsWeb, WikiTree, WeRelate, etc. For most people, it takes less than a day to connect to the World Family Tree. Really. Just ask a volunteer curator for help. Listen, unless you’re the stubborn type who still listens to music on an 8-Track player and watches videos on your BetaMax, you’re going to have to upgrade to Geni at some point. You might as well do it now.

5. Getting help is easier on Geni than anywhere else. I’ve already mentioned that Geni has a cadre of nearly 200 volunteer curators from all over the world who can help you with your tree, solve problems, untangle messes, answer questions and teach you how to use Geni. My friend Adam Brown refers to us as “park rangers.” The curators are elevated from the ranks of regular Geni users. Most have years of experience in genealogy and have contributed over 5,000 profiles to the World Family Tree. Some have accomplished seemingly superhuman feats (e.g., 500,000 merges or 200,000 profiles added in just 4 years). Curators can see private profiles to help users (because they sign a non-disclosure agreement), and can mark well-sourced profiles as master profiles, and lock fields to prevent changes. You can also find (or offer) help in a public discussion. Geni has a comprehensive set of Wiki pages that provide a wealth of information. And there is also a Help button at the bottom of your Geni home page that leads to a Knowledge Base where you can search through previously asked questions and take advantage of other self-help tools, such as Help Topics, Video Tutorials, and Community Help forums. Paying (Pro) users can also submit help tickets and get answers from Geni’s Customer Service department.

6. Your relatives will be more likely to collaborate on Geni. Here’s one of the big difference between Geni and the rest of the platforms. Sure, Ancestry will allow you to invite your relatives to join your tree and collaborate. But mostly your relatives won’t participate, and here’s why. It’s your tree. You only share a portion of your genealogy with your cousin, and she’s not likely to add her other branches to your tree. So for her, your tree isn’t complete and isn’t much fun. On Geni, there is no my tree and your tree. It is only our tree. Geni is like a giant jigsaw puzzle where everyone works together on the same puzzle. There is no ownership. You invite your cousins, and they invite their cousins, etc. etc. The tree grows and grows in all directions. Everything belongs to everyone and you work and add profiles wherever you can. Sure, they have privacy restrictions, mostly on the living portions of the tree. (I’ve written and spoken on these privacy issues extensively, so follow those blue links if you are interested.) But for the most part we all can and do work together on Geni. There are almost 4 million users connected to the World Family Tree. When you add and invite people to the tree, they’re going to be able to do as much as they will ever do. And they can do it for free, because Geni doesn’t require you to pay to work on the World Family Tree.

7. Geni is made for tree-building. I use the other major online genealogy platforms (Ancestry, MyHeritage, FamilySearch) almost every day, and am pretty familiar with how they operate. For the most part, they compete with each other as data aggregators, meaning that they are all scrambling to add and offer more and more data sets, like the U.S. census every ten years. For the for-profit companies, that is where the money is. Aggregate data and offer it to customers (for a price). Geni never played that game, which is part of the reason it was gobbled up by MyHeritage. The other platforms offer tree-building as a gateway to getting customers to pay for access to the data. MyHeritage now uses Geni that way, which is also a boon for Geni users who want to pay for that service. But Geni has always been about tree-building, and it has the best tree-building platform because that is all it ever wanted to be. I spoke last summer with Shipley Munson, the Chief Marketing Officer for FamilySearch, and he told me that they commissioned a study of all of the tree-building platforms and determined that Geni’s was the best and most user-friendly. It is. None of us who use all the platforms would be on Geni if it weren’t the best. Of course, all of the online programs are superior to the stand-alone programs in most respects. Even Ancestry has admitted that by announcing the discontinuation of its popular Family Tree Maker program. Sure, some other program might have this or that feature that you like, chart-printing or whatever. But none has nearly the number of great features Geni has. I’ll discuss some of these below.

8. Projects are the way to make progress. Geni set up a feature that allows users to create their own projects, which are essentially ways of collecting and organizing data and collaborating with other genealogists. There are many thousands of projects on Geni and more are being created every day. Basically you create the project page, which you can edit using rudimentary tools. Then you invite collaborators to join, so they can also edit the project page, start discussions, add photos or documents, and attach profiles to the project. There is such a wide variety of projects, it is hard to give an overview of them. Some are umbrella projects that provide structure and organization to a group of sub-projects. Some provide a common theme that ties together all the attached profiles. Here are a few, just to give you an idea: Passengers of the Mayflower, Finnish Priests, New Zealand Pioneer Families, Holocaust, and RMS Titanic.

9. Nothing beats Geni’s Relationship Finder. If you think that finding the shortest path between two nodes in a network is easy, you’ve probably never heard of Dijkstra’s algorithm. (You probably also never heard of the even more complicated Traveling Salesman Problem. That problem was the subject of my computer science final back in 1985. My algorithm came in third in a class of 100+.) Geni’s World Family Tree is a network of 100 million profiles, so finding a relationship path between any two profiles takes a lot of computer work. Geni’s algorithm is the best I have seen, and can often find paths between very distantly connected individuals, which makes the game “how am I related (connected) to X” a lot of fun. As an experiment, last year I decided to try to find a path between my son and the other 52 kids in his fifth grade class. It worked. I also set up the Jewish Celebrity Birthday Calendar, in part so I could test whether Geni could find a path between me and any of the 2,500 famous people I added to the project. It works pretty much every time. Recently I checked to see if I could find a path between my cousins, who have some deep American roots, and any of the U.S Presidents. It’s too much fun. Just connect to the World Family Tree and give it a try. The more connected your tree is (on all sides), the better it works.

10. Find and correct mistakes. One of the paradoxical things about Geni is that some people think the big tree has lots of errors when in fact it has fewer. Why is this? Because on Geni it is easier to find the mistakes. Every tree has errors and Geni has a ton of them for sure. Even if the error rate is just 1%, that would be 1 million mistakes in a tree of 100 million. But on Geni, you have millions of eyes scouring the tree all the time. The profiles are mostly public and easy to find using a Google search, thanks to Geni’s excellent SEO. So mistakes tend to get caught. The good thing is that you can fix mistakes, both yours and other people’s, which means that over time, the tree becomes increasingly error-free. The people who care the most about their branches make sure to keep them tidy. If someone makes a mistake nearby, they catch it and fix it. Curators can even lock down problem areas so they don’t get messed up by recurring errors. This doesn’t happen on other platforms, where you’ll find the same mistakes repeated over and over again, never getting corrected. That is why today there is no question that Geni’s World Family Tree is the most accurate and most comprehensive tree in existence.

11. Use it for free. It’s worth repeating. Everyone can use Geni for free to add unlimited profiles, merge duplicates, view relationship paths and upload up to 1GB of photos, videos and documents. Geni Pro members get some added features including access to tree matches, search, GEDCOM export, unlimited media uploads, and premium support. If you pay for MyHeritage, you get access to Record Matches with data (including U.S. census and FamilySearch data) and SmartMatches with MyHeritage trees. But unlimited tree-building is free on Geni. One essential tip: non-pro members can use Google search to find public profiles. Just add +site:geni.com to your Google search.

12. Geni is mostly public. You want your tree to be found. You really do. The best thing that can ever happen to a genealogist is having an unknown cousin make contact and add a branch to the tree. That won’t happen unless you put your tree out there for people to find. Don’t worry if it isn’t perfect. It will never be perfect. I’ve seen too many people hold onto their trees until they die, never allowing anyone to see anything. Don’t be that person. And don’t wait. The sooner you get things out in the open, the sooner people will find you. Thanks to Geni’s SEO, there is no better way to make your tree public than putting it on Geni. Ancestry and the other major platforms don’t allow Google to index all of their public profiles. So if you build your tree there, chances are only other users of those platforms will find it. Only Geni (and its much smaller imitators) make it possible for the rest of the world to find you using Google (the most popular search engine in the world with over 1 billion users). I’ve experimented by putting a large GEDCOM export of 100,000 profiles on Ancestry. I got almost no messages. On Geni, people contact me every day. You won’t believe it until you do it, but making your tree public on Geni is absolutely the best way for people to find you.

13. Be a part of a community of genealogists. Before I started on Geni, I basically worked by myself on my genealogy and participated in discussions on the Austria-Czech SIG mailing list. I had really no idea how much (or how little) other genealogists actually did. Geni opened my eyes. Now I could see the work of other genealogists from all over the world. And they could see mine. I could learn from how they did things. I could see who was speaking from experience, and who was just talking. Everything became transparent. Geni’s newsfeed is one of its great features. The work of everyone you follow or collaborate with comes in your feed, so you can see where they are working and help out if you see something. While I sleep, my friends in Israel and Europe are busy working on the tree. I wake up and see what they have done, and continue the work building the tree. Until you do this yourself, you have simply no idea what it is like, and how energizing and inspiring it is. You can even get a lot of the newsfeed in an e-mail. Sure, some people say all the notifications can get annoying, but you can adjust your settings if you don’t like them. I think the newsfeed and notifications are some of the best features on Geni.

14. Use discussions to solve problems. Geni has all sorts of ways to start discussions. You can start a discussion on a specific profile, or project, or just start up a discussion on a new topic. You can comment on a photo or document. You can send private messages or write on someone’s guestbook. There are so many ways to contact other people or ask for help. Working on Geni isn’t a solitary pursuit. Because everyone is working toward the same goal, a complete and accurate World Family Tree, you get answers. Problems get solved. There’s simply nothing like this on any of the other major tree-building platforms.

15. Geni is a global phenomenon. I try to concentrate on Jewish genealogy, but that’s just a teensy-weensy part of the larger puzzle. Geni has spread virally through lots of different communities throughout the world. As you might expect, the American tree is very well populated, but that’s not the only place where Geni is attracting attention. For some reason, Geni is one of the most popular websites in Estonia. Geni has users on all seven continents, in 235 countries and territories throughout the world. That’s good, because even around my family group (4th cousins + spouses), I have people who are from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Israel, England, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Holland, France, Belgium, Italy, Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Ukraine, Latvia, Slovakia, Serbia, Bosnia, Germany, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Korea, China, Japan, Viet Nam, India, New Guinea, Bali and Kenya. Geni’s platform allows for crowdsourced translations, so it works in 83 languages so far, and users are adding more translations all the time. In 2014 Geni added a unique feature allowing for multilingual profiles, which no other platform has. As the World Family Tree grows, Geni’s user base is expanding as well.

16. Enjoy genealogy for the fun of it. Most people just work on their own small trees, but on Geni, you can work anywhere. Suddenly genealogy is not just a search for your own past, but a way to record history for the rest of the world. Some people wake up in the morning and do a crossword puzzle. I do genealogy. It feels good, and productive. For example, my friends and collaborators on Geni are working through records in different areas of Bohemia and Moravia in the Czech Republic, building trees for entire communities. In the end, we’ll have a pretty comprehensive collection of interlocking trees covering an entire region. Because some 65% of Czech Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, we’re essentially rebuilding a destroyed world. Genealogy isn’t just an occasional hobby anymore; it’s my favorite pastime.

17. Learn about areas beyond your field. Being part of the World Family Tree means you are connected to everyone else, so you may end up exploring in places you would never otherwise see. And this is a great way to learn more about genealogy, and how to do genealogy. If you’re stuck in your area, see how they do it somewhere else. I focus mainly on 18th and 19th century records, but sometimes I look at what people are doing in earlier time periods, just to see what it’s like. It’s fun to plug in a historical figure like Charlemagne or the famous 11th century rabbi Rashi and follow the relationship path, learning about other historical figures along the way.

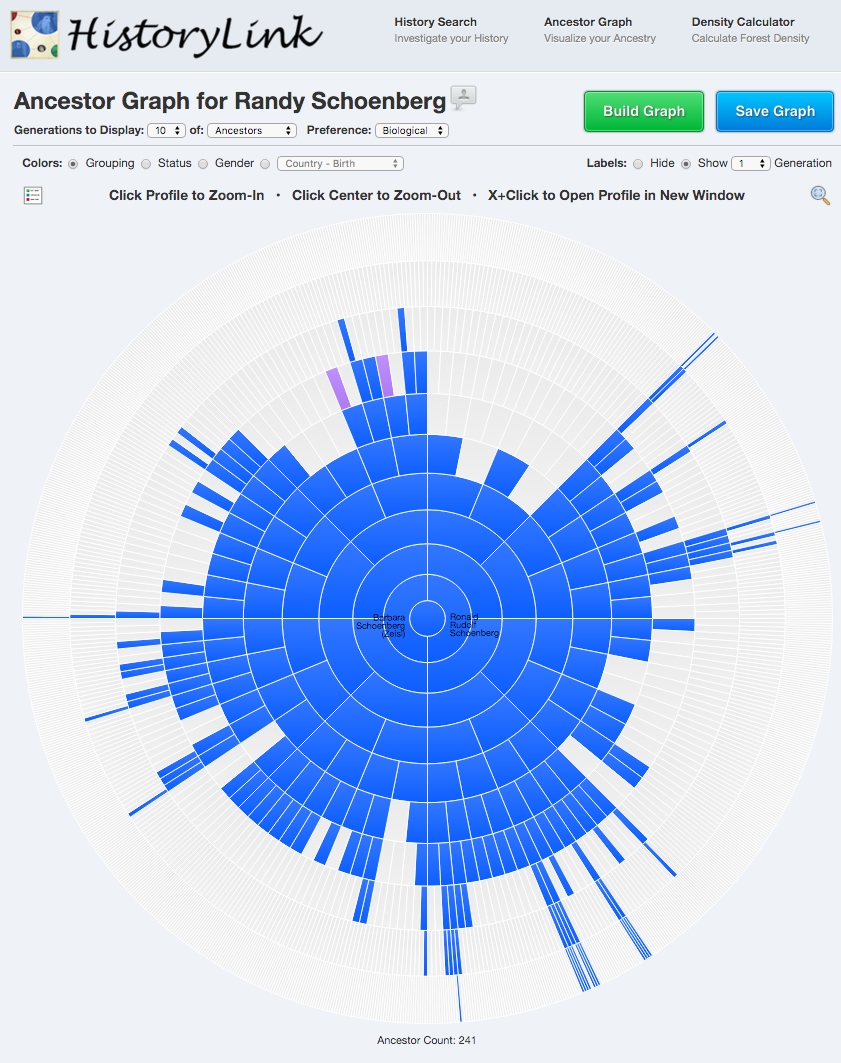

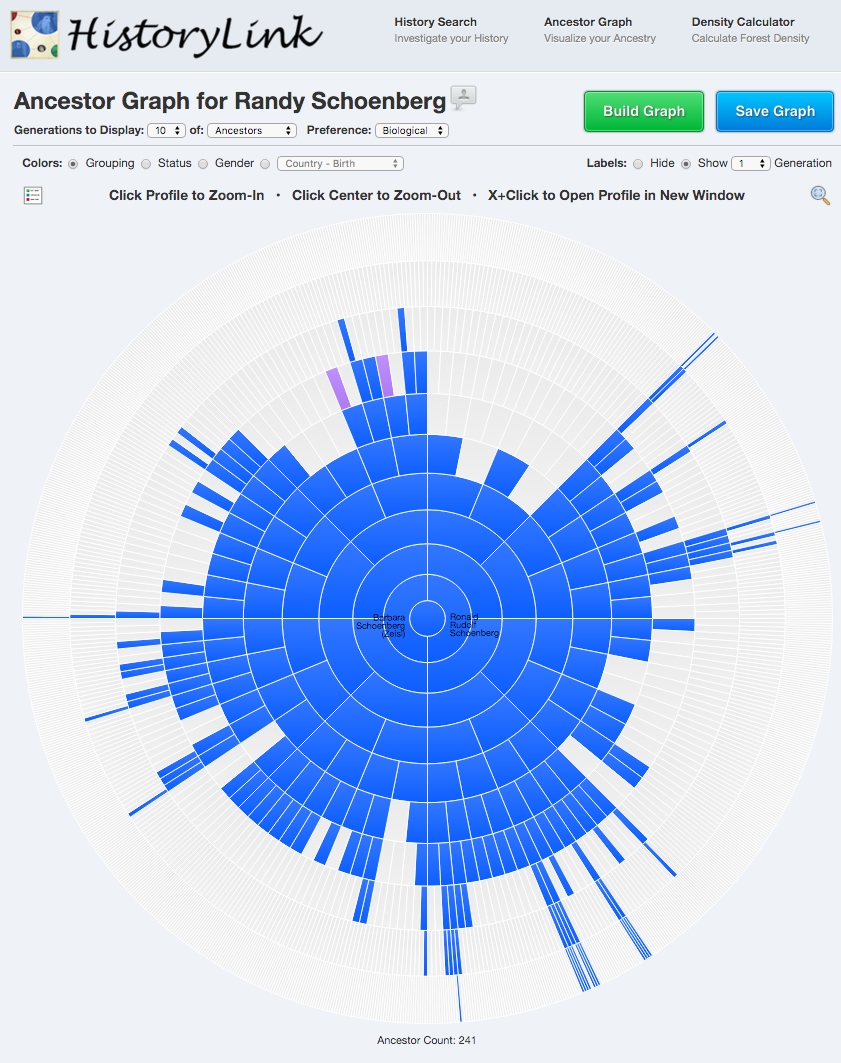

18. Geni’s open architecture means innovation. Geni allows programmers to develop apps that use the Geni database. Curator Jeff Gentes has created a number of good ones that you can find on HistoryLink, including hyperlinked descendant reports and this neat chart that allows you to visualize how complete your tree is.

19. Make your tree accessible to the people who want to see it. There’s probably only a small number of people who are really interested in your family tree. But why not at least make your work available to them. By inviting your family members to the tree on Geni, you instantly give them free remote access to all of your work. You can upload everything you have found — photos, documents, records and videos — and write family stories on the profile pages so that everyone who wants to can see them. That’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? Your kids and grandkids, nieces, nephews and cousins might not want to ask you directly, but they live online and if you make it available to them on the Internet, they’ll check it out. When someone tells you they scoured the tree looking for a family name to give their new baby, you’ll know you’ve done the right thing. (You can find the most common first names in your tree from the statistics page.)

20. Stop wasting your time, and mine. Your goal is to create a family tree with your relatives. The goal of Geni is to create a family tree with everyone in the world. These goals overlap. There’s no reason for you to be repeating work that has been done on Geni, and similarly there is no reason that people on Geni should have to repeat your work. All that time you spend sprucing your small, private tree is a waste, because it all has to be repeated on Geni. All the work you do correcting mistakes and documenting your sources will have to be repeated. The more efficient thing would be to do all that work on Geni.

21. Geni is the scientific method. The best way to make progress in an empirical field like genealogy is to use the scientific method. When you record an observed genealogical fact you are making a hypothesis (e.g., X is the husband of Y, or A is the son of X and Y). The next step is to test that hypothesis by placing it in the tree and seeing if all of the resulting relationship still make sense. Geni is the perfect place to test your hypotheses, because other people can view your work. Think of it like submitting an academic paper for peer review. There’s no better way to see if everything fits, or if you have overlooked something or made a mistake, than to submit your genealogical work to review by other genealogists. That is what is happening thousands of times a day on Geni, as people add information to the tree and their collaborators review them. Working by yourself, you will never be able to get the type of feedback and review necessary to make your work accurate. If you aren’t submitting your work for review on Geni, you aren’t really participating in the advancement of genealogical knowledge the way that Geni users are. This again is why the tree on Geni is in almost every instance more accurate, more documented, more verified than what you do on your own.

22. Help yourself by helping others. Every day I get about a dozen messages from users asking for help on Geni. As a volunteer curator, it’s my job to assist them, and I love doing it. I get to help and teach people how to use Geni, and in return I get to learn more about genealogy. There’s no replacement for experience, and Geni has given me much more experience as a genealogist than I ever could have had on my own, or even working as a professional on paid projects. I have no doubt that Geni’s curators are among the most experienced genealogists in the world, and I am proud to be one of them.

23. Take another look. Very often I look up people on Geni and find that they signed in once, maybe five or more years ago, didn’t find what they were looking for, didn’t add their tree, and never came back. A lot has changed on Geni since that time, and there have been many improvements. (Have you seen how Geni handles adoptions, for example?) But the biggest and most important development has been in the size of the tree and the level of accuracy. You need to come back and take a closer look. If you haven’t built out some of your tree on Geni and connected to the World Family Tree, you really don’t know what Geni has to offer. Over and over again I have had the experience of helping build out someone’s tree on Geni and making a discovery for them. This has been true even for the most experienced genealogists with very large trees on other platforms. You really won’t know until you try. So what are you waiting for?

Find me on Geni at http://www.geni.com/people/Randy-Schoenberg/6000000002764082210.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are my own and are not necessarily the views of Geni or its parent company MyHeritage.

P.S. If you want to see my tree on Geni, follow a link to one of my ancestors in the hyperlinked Ahnentafel report below (created using AncestorGraph on HistoryLink). Let me know if you find any mistakes. It’s always a work-in-progress.

Randy Schoenberg(1966 – )