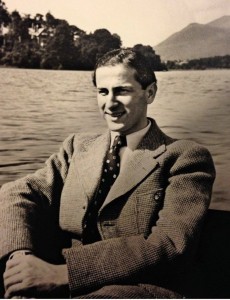

The following speech was prepared by Fritz Altmann (1908-1994) about his escape from Austria with his wife Maria Altmann née Bloch-Bauer (1916-2011). Fritz is portrayed by Max Irons in the 2015 film Woman in Gold. For further details, see also the essay of Fritz’s older brother Bernard Altmann.

Gentlemen,

I am deeply grateful for the interest you show for me and my experiences and it is a pleasure to tell you, the citizens of a free country, of what can happen and has happened in other countries in Europe not at all far from here.

The Austria from 1918 to 1928 had been a free and progressive country – free from hard political feelings. There was a free press and the possibility of free speech for everybody, and a hard-working Parliament.

It is a pity that Austria was not able to follow this line longer than 10 years.

After this period the party of Dolfuss and Dr. Schuschnigg started to curtail the freedom of the people more and more.

At last, some 5 years ago the Parliament was dissolved, the freedom of press and speech was stopped, and citizens who intended to defend their freedom were shot.

Vienna was a battle-field for 2 days, and Dolfuss and Schuschnigg established a new politic, which was the beginning of the end. I had been living in Vienna, capital of the former Austria, where my eldest brother had a factory with approximately a thousand workers.

A short time before Hitler came into Austria, I married, and this is just a time when one is not too interested to look at newspapers, and so I was rather surprised that one day, almost overnight, the situation had changed; good and well-known citizens were despised only on account of their personal feelings or thoughts or religion if different to the Nazi ideas. Nobody was allowed to have a personal opinion – everybody must think alike.

My brother, the owner of the factory, had not been in Austria at that time, and it was not enough for the Nazis to take his house and all his belongings and the whole factory – without taking the trouble to look into the facts of rights or wrongs – and without trial they took away all the possessions of our family.

The method was very simple. A young boy of 25 years came into the factory one day, showed a badge of the Secret Police and told us that this organisation had taken over the factory and all belonging to it, and another even younger man, without the slightest experience in the class of business, had been detailed to act as commissar. But even this was not enough for the Nazis. A large part of the trade was in export, and they could only take over the bank account in Germany but not the money outstanding against accounts in other countries where right is still right. They, therefore, decided to force my brother to transfer all foreign accounts to them, and they followed the method – which is the gangster’s method – and took a hostage.

I was taken for the hostage, and was imprisoned for 3 months during which time nobody told me why, for how long, or to what purpose. Not once was I given the opportunity to state my case nor did I see any responsible person to whom I could tell my story.

In the meantime, the new owners of the factory went to Paris to meet my brother, and told him that if he wanted to see me again, he would have to transfer all his foreign possessions including the factory he has in Paris, and he would have to declare that he would not start a new factory anywhere in the world, and further that he would help the export trade of his former Viennese factory.

My brother told them that he would not make any agreement before I was released, and a short time later I was sent home.

In order to tell you my experiences I have to state first that I was in a Viennese prison for 3 weeks, and although I have not had experience in a prison in any other country, I think the conditions were at least not worse than those in any other such place, the reason for this being that our guards were Viennese.

The Viennese people are quite civilized and not to be confused with other Austrians, who are Germans. The reason for the difference may well be that in Vienna, capital of the former Austrian Empire, for hundreds of years the citizens have been a mixture of all the nations of the Austrian Empire. There is an old. Viennese proverb which says “Every real Viennese is a Hungarian or Czech.”

One night a couple of hundred prisoners were brought to the Railway station where a special train was waiting to take them to the Concentration camp at DACHAU. I was one of these -prisoners, and I will never forget that journey as long as I live. We were all sitting very close together the whole night in a railway carriage. In every compartment there were one or two young men – only 16 or 17 years of age.– members of the Storm Troopers who were really pleased to torture their unfortunate victims.

We were forced to sit the whole night without the slightest movement, and to look straight at the light in the carriage; each blink of the eyelid was enough to cause a hard blow to the head with the butt of a rifle. It is almost impossible to explain what ideas the young boys had for new tortures. I have only to say that a few of us were contemplating trying to jump through the closed window of the fast moving train, as the sure death seemed preferable to sitting in the carriage.

Among the prisoners were a number of the best known men of the former Austria, including ministers of the State (one being a personal friend of Dr. Schusehnigg), the Managing Director of the Austrian Railways was sitting on the floor of my carriage, his face streaming with blood. Also clergymen and a number of men who were officers during the last war, and had been decorated several times. A Couple of Artistes were in the same transport – top line comedians whose only fault had been to joke about the Nazis in the years before.

After our arrival in the Concentration camp, we were without food or drink for more than 24 hours, sitting upright or standing perfectly straight the whole time.

The start of the life in the Concentration camp seemed to be a relief after the journey. It was, however, very hard; not for me as I was young and athletic and had always been very fit, but it was terrible to see old men of 60, 70 and nearly 80 years having to do the same hard work from 3:30 a.m. until 9:00 p.m., and the most cruel punishment was inflicted if they rested for a minute, or could not do the work required of them.

As on the journey, the guard at the Concentration camp was composed of boys of 16 or 17 years.

The Concentration Camp at Dachau is a very large ground – a couple of square miles, with a large yard in the middle where the prisoners had to spend a few hours every morning and every evening, standing in line to be counted, to check if anybody had escaped.

One day we had to stand a few hours extra as one man was missing, until the guard found he had forgotten to allow for the fact that a man had died the same morning.

Round the camp was a wide and deep trench, and outside

of this a high barbed wire barrier, which is electrified at night. At each corner is a tower on which guards with machine guns were posted day and night. Every night the whole camp is as bright as day, with search-lights.

We were living in huts, the walls of which were made of a kind of corrugated paper; these huts were very clean and modern, and we slept 50 men to a room. The food was fairly good and it was possible to obtain supplementary rations with money received from home.

The food and living conditions were quite human, the very bad part was the treatment, the kind of work required, and the hard punishments which were continuously being meted out.

It would take a long time to explain all the trouble and the treatment in the Concentration camp, being too bad sometimes even for animals to endure, and in spite of this I have to say that I saw the Concentration camp at its best. It was spring, the weather was nearly always fine, and there were 5,000 men in the camp which was therefore not overcrowded. My poor friends, with few exceptions, had much worse times later as there have been as many as 15,000 and they have had to stand perfectly still hour after hour as there was not room to sleep. Once, in January they were forced to stand perfectly still the whole night out of doors.

But I should also like to relate one amusing experience. There were among us a few hundred burglars and I must say they were the most interesting people of all. Nobody could tell such humorous and interesting stories as these fellows. One day during working hours I had the luck to be with one of them. After telling him who I was he started to give me a full description of our factory, with all details of our cashroom, and told me exactly when we had been in the habit of sending for money from the bank and when we paid our work-people, at which hours the watchman made his rounds, and the size and breed of his dog.

He was the thief who had entered the factory some 10 years previously, opened the safe and relieved the firm of a considerable sum. He also told me that never in his life before or since had he been so successful and so he would never forget the name of the factory. Half of the sum obtained had been sufficient for his accomplice to drop his profession, go to the United States and establish himself as a respectable citizen.

At that moment I was envious that I was the person from whom he had stolen and not the one safe in the States.

This robber and I became good friends; many of my evening and Sunday hours have been made brighter by this friendship.

One night I was released and I regretted that I could not take my friends with me to freedom. But it was not freedom that was waiting for me. I was brought back to Vienna and confined to my home for 3 more months, because the Nazis were unwilling to let their hostage free until they had taken the last penny from the pocket of my brother.

I, therefore, started planning to escape. Three times I attempted without success, but in spite of the watchfulness of the Gestapo, nobody was aware of these attempts.

The fourth time was luckier. I left my home in the morning having received permission to make one of my trips to town for a few hours. My wife and I went to the aerodrome and boarded a plane. My wife’s passport was quite in order, but she would not let me try to escape alone. My passport had been taken away from me, which of course, added to my difficulties. In the afternoon we were in Cologne, then travelled by train to Aachen and motor car to the small house of a peasant on the Dutch border. We arrived there at 9 o’clock the same evening; after a few weeks of correspondence directed to a friend of mine, we had an appointment with the peasant, and a few minutes later he was leading us. We were jumping over stepping stones in a little brook, then climbing over barbed wire barriers, to Holland. The night was very black, the moon was not shining, just the stars in the sky.

At the same time the Secret Police were issuing a warrant for my capture to all the border countries.

Our arrival in Holland was one of the happiest moments of my life, but even now we were not sure of safety because the Dutch Police used to send back to the German frontier, all people whose passports were not in order.

My brother, who was in Amsterdam at this time, was careful to send a well known Dutch Lawyer to escort us and the next morning we arrived in Amsterdam. There we boarded an aeroplane and flew straight to Liverpool, where we landed the same afternoon, having received permission from the Home Office to land without a passport, and when I told the Immigration Officer that I had no passport, he smilingly said, “Yes, I know,” and his only question was “Did you get well over the border?”

I am sure that I would not have received the same treatment in any other country in the world.

When I consider the whole matter, I really have the longing to shake the hand of every English man I meet, and to thank him.

I think that the majority of people born and living here do not realize the difference between this and other countries.

When you are tempted to take for granted the blessings of this country, I hope you will think of my today’s talk and appreciate the freedom and happiness which is yours.

Thank you for posting the stories of Fritz and his brother. It added so much background to the movie, which I enjoyed seeing today. I had questions that were answered on this site. I also enjoyed the music soundtrack.