I went this week for the second time to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) to see the big new exhibition entitled From Van Gogh to Kandinsky: Expressionism in Germany and France. I had high hopes for this show. Thanks to the Robert Gore Rifkind collection at LACMA and the Galka Scheyer collection at the Norton Simon Museum, Los Angeles can boast the best collection of Expressionist artwork anywhere outside Germany and Austria. A blockbuster international show highlighting the Expressionists would be a welcome antidote to the steady stream of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist exhibits at LACMA and most other American museums.

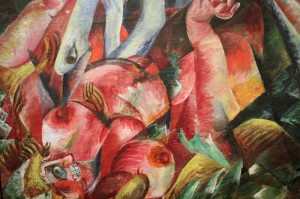

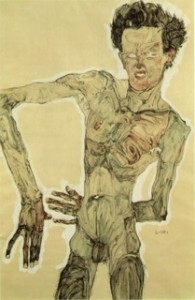

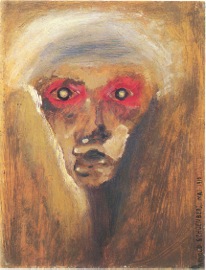

The show presents a vast array of works by artists associated with the two German Expressionist groups Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). The main argument of the show is that these artists from Germany — Kirchner, Heckel, Nolde, Pechstein, Kandinsky, Marc, Macke, Jawlensky, Schmidt-Rottluff and Feininger — were influenced by the artists in France — Van Gogh, Matisse, Gaugin, Derain, Dufy, Picasso, Rousseau, Signac, Braque, and Cézanne. Indeed, the wall panel introduction asserts the “conversation” between Germany and France was the “most significant” influence on the Expressionists. While the artworks presented certainly demonstrate that the German artists imitated the Post-Impressionists and Fauves early in their careers, what is almost entirely missing from the show are any actual works that one might call Expressionist. By focusing on only the color palette, and not the actual content of the works, the curators have entirely missed the point of what Expressionism was supposed to be. Expressionism was not necessarily a new direction in art. There were many precursors, including, for example, Grünewald, Goya, Turner and Munch, artists whose focus was on the expression of deep, often dark, mysterious emotions. The major French schools — Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Fauves, and Cubists — studiously avoided this type of heart-on-your-sleeve emotionality. Perhaps the distinction is best explained, not by words, but by pictures. Here are three works from 1910 by the Austrian Expressionists — Kokoschka, Schiele, and Schoenberg — all of whom were consciously excluded from this show.

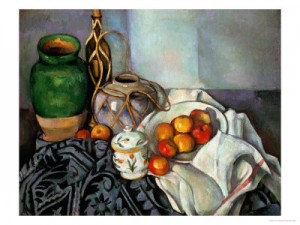

These are all undoubtedly works that one would label Expressionist. Now, what do they have in common with Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples (1893-94)?

What about Gaugin’s Polynesian Woman with Children (1901)?

And can you see a connection with Van Gogh’s Restaurant of the Siren at Asnières?

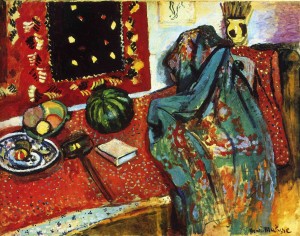

Ok, last one. Can you see the influence on the Austrian Expressionists in Matisse’s Still Life with Red Rug (1906)?

The answer is: you can’t. Of course, if you are trying to make the case that the German Expressionists were mainly influenced by the French, then you have to choose only their works that show that influence, which is what the curators of the show do. Over and over again, the curators take works that are obviously imitations of the French, rather than the later works that we all have come to know as Expressionism. The few exceptions in the show stand out like sore thumbs.

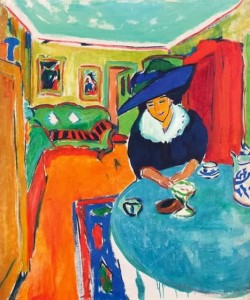

So, it is true that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s 1909 Dodo at the Table really does look like a Matisse.

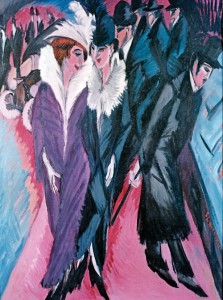

But his Street Scene from 1913 really does not.

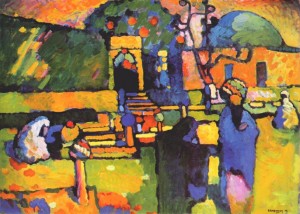

Wassily Kandinsky’s Arabian Cemetery (1909) really does almost look like a Fauve work by André Derain.

But his Sketch I for Painting with White Border (1913) really does not.

What is missing from this show is anything that shows what German Expressionism really was. Fortunately, you can walk over to the Ahmanson Building at LACMA and see highlights from the Rifkind collection, including this 1919 Expressionist masterpiece by Otto Dix.

But you won’t find anything like it in the blockbuster Expressionism show.

The truth is that German Expressionism was not chiefly an outgrowth from French art trends. No doubt the Dutch (living in France) were a great influence. The examples from Van Gogh and Van Dongen in the show really are terrific and certainly do point the way to Expressionism. But Expressionism as a movement was not really about the imitation or appropriation of the French color palette. It was the idea, not the style, that made Expressionism.

In sum, the Post-Impressionists made great innovations in style (palette and technique), which the artists in Germany who later became Expressionists all tried early in their careers to imitate and adopt. But the bottom line is that Post-Impressionist painters for the most part were still painting pretty pictures of pleasant scenes. The Expressionists, when they finally hit their stride, were emphatically doing something completely different. The LACMA show is just an excuse to once again put together a blockbuster Post-Impressionist show (Van Gogh, Matisse, Cezanne, Gaugin, etc) with some derivative early works by the Die Brücke and Blaue Reiter artists. We’ll have to wait for a truly great show on Expressionism, one that does not limit its focus to just the German artists, but includes the Austrians too. Because you cannot explain works like Kokoschka’s 1913-14 Bride of the Wind by looking to France.