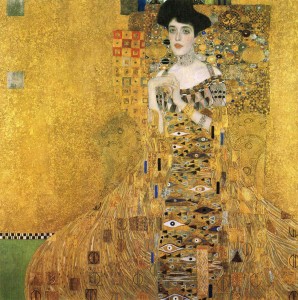

What follows is Bernhard Altmann‘s description of the circumstances surrounding the escape of his younger brother Fritz Altmann (1908-1994) and his wife Maria (1916-2011) from Nazi Germany, an event portrayed by Max Irons and Tatyana Maslany in the 2015 film Woman in Gold. The text was translated by Bernhard’s son Cecil Altmann for Fritz’s 80th birthday in 1988. Fritz and Maria were married December 9, 1937 in Vienna. Nazi Germany annexed Austria on March 12, 1938. Fritz and Maria’s escape took place on October 21-22, 1938. For further details, see Fritz Altmann: My Adventures and Escape from Nazi Germany.

I had taken residence in Paris and was rapidly making my plans for the future.

An expansion of the Paris factory could not be taken into consideration because the French market was not large enough for our products, certainly not to be able to create a subsistence for my large family. It was also clear that I would not be able to get sufficient working permits for the many members of the family.

I thought first of going to the United States and building a factory there. On the 31st of March, I took a visitor’s visa to go to the U.S. That turned out to be very wise because later such visas could be obtained only with great difficulties.

In April, I went to England and started discussions with the government. In May, I was to obtain an answer. When I went to London in May, I was not given a definitive answer. The Scottish knitware manufacturers had objected to the granting of an entry permit for my family and myself to the building of a new factory.

After fourteen days, I decided to follow-up on an offer made by Sir Frederic Marquis and went to Liverpool. I was welcomed there and at a lunch that the Lord Mayor held on June 1, I concluded an oral contract with the key officials. A factory would be built for me, and I would only have to lease it. After three years, I would have the right either to discontinue the lease, to continue it, or to purchase the building at that time. Martin’s Bank offered me a 5 years credit of a minimum of 10,000 pounds (which we have not drawn on to date).

Then I went to Paris and sought means to bring my family out of Vienna.

Max had become a sales representative for the Vienna firm, travelling to France and England. He begged me in the name of the family to forego the new establishment in Liverpool. It seemed to be the main concern of those family members of the family remaining in Vienna not to make any waves. They were concerned about my keeping some of my assets but did not see that everything was lost and there was only one task ahead: finding every possible way to bring the family members out of Vienna.

Instead I had a multitude of wishes, communications and requests not to establish anything. This to avoid reprisals against the remaining family members.

I did not let myself be deterred from my task. Even if certain members of the family would be taken into custody – Fritz at this time had already been taken into the Landesgericht – after their release they could have an entry possibility to England and even a job. Without this, they would come to naught in Vienna and I could not do anything for them.

Max wanted to travel back to Vienna and I kept him from doing this. I had to beg him to stay.

In August, Julius came. When I asked him before his departure not to come to Paris before Trude and Nelly were out of Vienna, he hung up the phone up on me angrily. As he had come without Trude and Nelly, I asked him to stay because each member of the family out of Vienna was for me a relief.

Clara and Liselotte Herlinger had both received passports. I asked Clara to go to Italy immediately. Nothing stood in a way of her departure. However I heard nothing but excuses from her. She could not leave for one or another reason. Her son Gerhard – a marvelous young man, who lived with me in Paris 3 months – was also very upset. I could not give credence to all these excuses.

Despite these difficulties, she finally travelled to Italy. There I could take care of her because there were some Lira in my Italian company.

Shortly thereafter, Titti, the wife of my brother Max, came to London with her daughter.

Thus only Nelly, Trude, Fritz and Maria remained in Vienna. My brothers had made the mistake of picking the wrong Vienna attorney. Our case was given to a man by the name of Hentschel. He was more afraid of the Gestapo than we were. And he obtained nothing. It would have been better had we had no lawyer at all. In September, I decided to send a former administration employee named Robert Luthy to Vienna to help matters along. He did obtain the promise that Nelly and Trude could leave Austria.

I have to say about my wife Nelly and also of Trude that they behaved extremely well. I had not the slightest complaint from them and the letters that Nelly wrote me were heartwarming. She sought to calm me.

In the middle of September, I decided with an attorney from Brunn (Czechoslovakia) to obtain the departure of the four remaining family members to that town. It was all prepared. In Prague, the permission from the government had been obtained for temporary passports. However, this effort failed.

On October 5, I decided to go to Holland. I had heard that the crossing of the border to Germany was relatively easy. I booked a flight from Manchester to Amsterdam. On the 5th of October in the morning, there was a storm in England that caused a dozen or so casualties, hundreds of trees were uprooted. I did not let that get in my way and drove at 6 in the morning to Manchester and took the plane to Amsterdam. We had a tailwind – rather a tailstorm – and landed in the record time of one hour and 17 minutes later in Amsterdam.

I drove to the border, viewed the crossing possibilities and thought those dangerous. Every railroad crossing, every bridge was watched by border guards. When I talked to my Dutch friend C. in Paris a few days later, he advised me differently and counselled me to pursue the Dutch border crossing plan.

On October 12, I was able to receive Nelly and Trude in London. I then decided to bring Fritz out. And went to Paris on October 13.

Now I wish to tell the story of the events that led to the successful escape of my brother Fritz and his wife Maria.

The rules of classic greek drama require unity of time, place and theme. The Schiller drama William Tell is perhaps the best example of this. He follows the rules and his drama is further divided in three sections: the Tell-, Gessler- end the Attinghausen tales. As it happens, the tale of my brother’s flight also follows the classic rules. This drama, – although with a happy ending – also has three parts: the German, the Dutch and the English.

My brother was in contemplation of an escape for several weeks. His first idea was to get a Yugoslav passport. He should have got one on October 20. However the people who should have gotten it for him were arrested and thus this plan came to nothing.

An escape to Luxembourg was also considered and dropped.

Finally, Fritz agreed with my suggestion to go across the Dutch border.

Our correspondence was thru a good a friend of Fritz’s, Nissel. He brought the mail regularly to my brother in his apartment at the factory where he was under house arrest by the Gestapo.

The porter at the factory had the obligation to tell the Gestapo if Fritz were to leave without permission.

I advised Fritz that it would be best to tell the Gestapo agent Landau that he had to have dental treatment. In this way he could arrange regular departures from the factory. He did this. As he wrote me that it would be probable that an SS man would be given him as a guard, without whom he could not leave the factory, I made out [the] following plan: He should go with this man to the old Bristol Hotel and ask him to wait in the hall. Behind the hall there is a bar with an exit to the Mahlerstrasse and there one always finds a taxi with which Fritz could go then either to the railway station or to the airport.

On the 10th of October, Fritz left the factory and we talked on the telephone and finalized all plans. I left Liverpool, flew to Paris and met my cousin Isakower who went with me to Holland. Max Isakower, 28 years old, had gone from Paris to Vienna three times, and this without passport. He went over the French – Belgian border and the Belgian – Dutch border at night, and then over the Dutch – German border. He had some modest amounts of money in Vienna which he wanted to bring out, and he did this in this fashion. I took him with me so that he would fetch Fritz in Cologne and then bring him to the Dutch border.

Early in the morning, we drove out to Le Bourget, had some difficulty there because Air France wanted us to sign a declaration that we understood that we were going to Holland at our own risk. Since there was no need to have a visa, it was at the discretion of the police authorities to permit Austrians to enter or to be turned back. The only time that I had a strong heartbeat during these three days was then because I feared that the Amsterdam police would turn me back. But it was without a problem. And so I got to Amsterdam with Isakower and agreed that we would go to the border as soon as possible.

Isakower was to cross the border at Keerkrade in the night of October 20. This was the Dutch border town. From there, he would go to the German border post Kohlscheldt and go to Cologne and meet Fritz on October 21 at 3 p.m. at the Dom of Cologne.

To cover contingencies, we agreed with both Fritz and Isakower that in case something were to go wrong that the concierge of the Dom Hotel would be given a message for Mr. Fritz Hooper. This was the cover for any necessary communications.

At eleven o’clock in the morning of October 20th I said goodbye to Isakower.

Now the drama unfolds and I wish to tell the Dutch part first.

I went to my friends C. to get advice from them. Mr. M. C. would give me his full help, wanted to lend me his car so that I might pick Fritz up at the border and drive him to Amsterdam. I thanked him very much and I said “Listen, my dear friend, you are a Dutch Jew; as such I can’t bring you into such an affair which is not permitted under Dutch law. I thank you for your wonderful and humane help. I would be indebted to you if you would only give me a good and reliable attorney.”

And Mr. M. C. then gave me the name of a wonderful man, Dr. X.P., to whom I went immediately after lunch. I told him my story which he understood in its full importance and seriousness. To my great regret, he had to leave the next morning and was therefore not in a position to take this case on. He did however let me know that I would have his full support and that he would be available for me in the evening.

The marvelous thing in all this tale is that at various points, it looked like the whole scheme would fail; as in a tragi-comedy, all the missed opportunities resolve themselves in a happy ending.

So I was in the apartment of this wonderful lawyer Dr. P. and we developed our plan.

One must keep in mind that the southern-most province of Holland called Limburg was at that time in [a] state of alert with regard to all illegal immigrants.

Since hundreds of German Socialists, Jews and Catholics transited there every night, the Dutch Government had reinforced the customs posts. In the little stretch Heerlen – Keerkrade there were at least 50 border policemen.

I then related my plan again in all its details. My brother was to depart on the German Lufthansa flight an October 21, 1938, at 9:45 a.m. He should thus reach Cologne at about 3:30 p.m. In front of the Dom, he was to meet my cousin Isakower and then go with him to Kohlscheidt. There, he was to wait with farmer H. Senior till evening. H. Senior should then bring him to the border under the cover of night. On the Dutch side, the son of H. Senior should then take Fritz to his house in Keerkrade. Where Fritz and his wife were to spend the night.

The wife of my brother Fritz – Maria – said that she wanted go with Fritz although she had a valid passport and visas for entry into France and England. Like a biblical heroine she stayed faithfully by the side of her husband to whom she had sworn her troth ten months earlier.

With Dr. H. I discussed that he would travel to Maastrich on [the] evening of October 21. There he was to spend the night in the Hotel Lievre [???] at Aiglon. In the morning of October 22, my brother was to leave Keerkrade and go with him to Amsterdam. In case something were to happen at the border, Dr. H. should try to make an official intervention.

The border police had the task of hunting down people coming from Germany without an entry permit and then to turn them over to the German authorities without further ado. Such money that the refugees had was given to the border SS. Dr. H. promised in case any tragedy were to befall us that he would arrange for custody for my brother in Holland.

Now it became necessary to provide entry for my brother to England. And I would arrange for the necessary documents.

Dr. H. was to travel with these documents on the 21st of October to Maastrich. I spoke with him at 11 on the 20th of October and sought to give him the documents.

According to the old rule I adopted, that an officer of the general staff should not go to the front, I took my quarters in the Hotel Victoria in Amsterdam and this was a good thing.

I operated from my room and by telephone. I spoke to Fritz as agreed on the 20th of October at 4 p.m. in Vienna and confirmed that everything was in order.

I called my son Hans in Liverpool. And this was our talk:

“Listen, my son, tomorrow Fritz should come to Holland. He would have a false Czech passport with which to come to England. While need creates expedients, it would not be good to start a new life in wonderful England with a lie. Go to see our protector in Liverpool, Sir Frederick Marquis, and tell him the situation. Ask him for a police document whereby Fritz would be let in to England.”

Hans told me that he thought this impossible.

“A lazy servant is a half prophet – says the old Jewish proverb” said I to him, “go and do what I ask of you.”

Hans was to express mail the entry permit for Fritz.

But let us return to the Dutch part of the story. On the morning of October 21, I went to the air company KLM and asked for the rental of a plane for the next day. I was told that only larger planes of the Douglas variety were permitted to fly over the channel. Such a plane – a 14 passenger plane – would cost 1180 Florins for the flight to Liverpool. I did not want a firm rental as something might still go wrong. On the other hand, I wanted to arrange that Fritz end Maria would not spend a minute longer on Dutch soil than would be necessary.

The KLM official asked for a large down payment. According to a principle learned from my mother I did not want to give anything as a down payment. Finally, we agreed on a sum of 50 Florins for which I got a receipt.

In every serious story there is a touch a humour – and I laughed very much when I saw on the corner of the receipt, the words, in Dutch: “EXTRA VLUCHT.” *

*Translator note: the German homophone, Vlucht, means escape.

At one o’clock in the afternoon, a courier from Liverpool should have brought the letter. He brought nothing. The concierge of the Hotel told me that the next mail was only at 7 p.m. But then Dr. H. would already have left. I went to the central post office, and asked the different departments whether they had not found an express letter. And I found the letter in one of the departments.

I thus went to Dr. H. and gave him the English entry permit which had been in the letter, the receipt from KLM and also photos of Fritz and Maria. With best wishes for his travel, I said goodbye to this excellent man.

On Friday afternoon, I did several errands, and went to the hotel to call Liverpool. At this point, let us go back to the English part of this saga.

Hans did go immediately to Sir Frederick’s office and found out that he had left the very morning for South Africa. He then went to Alderman Shannon who heard his story out and declared his willingness to help. He recommended him to the chief of police of Liverpool, who was not in his office. However, his assistant declared to Hans that such a permit was outside the authority vested in him. He would however get in touch with the Home office. He did this immediately over the phone and official there asked what interest the city of Liverpool had in the entry of this man. He answered that we were building a factory in Liverpool and that all the family was reunited in England with the exception of Fritz, and that Fritz had spent some time in a concentration camp. The Home office gave its approval right on the telephone and said that Fritz could enter into England without a passport. That police official immediately gave his assurance that the next afternoon – Saturday – both an official of the Immigration service as well as a Customs official would be advised that Fritz could enter the country without any further formality. This closes the English part of the story.

With some excitement, I awaited the evening. I agreed with Fritz that he would send no messages.

At 8 p.m. I had to be in the hotel because they advised that there would be an air raid alarm. All Amsterdam was made dark and the hotel was candle-lit like a church. The candle light gave the whole picture an additional element of ambiance. It was muggy in the hotel and the hall was not inviting.

I went first to my room, then down to the lobby. It was 9, then 10 p.m. I had to get some air, but I could not leave the lobby because [at] any time there might be a call. At 10:30 p.m. I decided to go on to the street for 5 minutes to catch a breath of air. I was out on the street only for 7 minutes and as I went back the telephone operator told me that there had been a call from Heerlen. Mr. Max Isakower was on the telephone, gave his number and asked for a return call.

I got a connection immediately and within 5 minutes I got Isakower who told me that Fritz had crossed the border successfully but had not been able to spend the night at H. Junior’s place in Keerkrade as planned but was already 7 km from the border at Heerlen where he was the guest of a bicycle dealer. He could not explain this on the telephone. Fritz and Maria could not spend the night there at any cost. What should he do?

I said that Isakower should immediately take a taxi and go to the Hotel Lievre & Aiglon in Maastrich. There he should ask Dr. H. that he should go with him to the town of Heerlen, 27 km away, to fetch Fritz. Under the direction of Dr. H., they should then go back to Maastrich to the hotel. Isakower immediately went off to Maastrich.

Then I Immediately called the hotel in Maastrich to speak to Dr. van H. He had gone out.

I asked for a connection with Heerlen again because in my haste I had forgotten to speak to Fritz. I wanted to give him courage, should he be in bad spirits. I had not told them about the dangers on purpose because I did not want to trouble him needlessly.

He came to the phone and was in full good mood which made me happy. He had just eaten very well and was waiting for Isakower who was supposed to bring him to Amsterdam in some fashion. I was very happy to know him in such good spirits and promised him that we would meet the next morning in Amsterdam. How that could be arranged I did not know at that time. But I had confidence in my lucky star.

A few minutes later, I spoke to Liverpool and to Paris and told Max and Julius that Fritz was in Holland. Their relief was immense. Yet I was not comforted.

It was at 1:15 that I got a call from Maastrich. Isakower was on the phone. He had been stopped 3 times on his way to Meastrich by gendarmes. On the way back to Heerlen, another time. The clever fellow had come up with a good plan at this time. At 12:20 a.m., the last train leaves Heerlen to go to Maastrich. He took a taxi with Fritz, Maria [and] Dr. van H. to the railroad station. They were there at 12:18 a.m. He quickly took tickets and they hopped on the train so that the policeman who was on duty did not have time to ask them anything. And in half an hour, they were in the hotel in Maastrich. Dr. H. was well known there so they did not have to register. Isakower made an arrangement with the concierge that the door be locked because there was a usual round by an inspector of the police at 2 a.m. to check on the guest list. To avoid further complications, not only was the door locked, but the bell was disconnected. As I had this news, I did have a moment of relief because I told myself that not much could happen anymore. If, by any unhappy circumstances, Fritz would have been taken by Dutch authorities, he would be put into their custody and not turned over to the German border police.

I then informed my family by phone of the improved position.

What had happened in the meantime? How come had Fritz not spent the night at H. Junior’s in Keerkrade?

Now I have to return to the German part of the story.

No! First I have to record that Max Isakower never went to Cologne. What had happened in the meantime, I could not know. The border from Holland to Germany could not be crossed that night, for some reason. Max Isakower was to have contacted some German coal-workers who worked in the mines in Keerkrade and daily went back over the border to Kohlscheidt in the evening. He arrived too late and could not go over to Germany anymore. He had however told the father of H. in Kohlscheidt, to pick up Fritz at 3 o’clock at the Dom.

Senior was there. He asked at the Dom Hotel if there had been any message for or from Fritz Hooper. The concierge said, “Yes, a telegram is here.” The old H. took the telegram and its content was “Cannot travel because of illness.” The telegram was directed to a Fritz Leeman but the old farmer who was used to code names thought that could only be for Altmann. Therefore he went back to Kohlscheidt.

Now back to Vienna.

Fritz had left the factory at 9 o’clock, and got to take the 1:45 plane to Frankfurt. He took the ticket in the name of his friend Nissel whose passport he had in his pocket.

A pair of dark glasses and a stern look on his face should have made him resemble the picture on the passport more closely.

Fritz and Maria flew to Frankfurt, changed planes and were soon in Cologne. At the Cologne airport, a stewardess from Lufthansa asked if there were two passengers from Vienna in the group. Fritz and Maria did not answer the call but were unsettled by this query. They arrived in the city and waited a while in front of the Dom – which in our telephone calls we always spoke of as the little church – saw nobody and then asked in the Dom Hotel if there has been a message for Mr. Hooper. Yes, the porter said. The elderly gentleman had taken the message and left.

What a comedy of errors!

Fritz decided immediately to take the next train to Aachen. There, they put their baggage in storage (which would be an important element later) and took a taxi to Kohlscheidt. They gave the chauffeur [the] address of the elder H., who did not know the street. However he drove off rapidly and wanted to go to the border post to inquire of the SS man the directions to the well known smuggler.

Fritz was able to stop just before the border post and paid the taxi off and started off on his own to find the eider H.

He did not find the address immediately and asked a young Catholic priest. This priest brought them there immediately.

It was then 4 o’clock in the afternoon and far too bright to try an illegal crossing of the border. So they waited at the house of the old couple until the start of night.

Because the Gods were so favorable to this undertaking, there was no moon that night and it was very dark when Fritz and Maria were under way under the direction of the old farmer.

They came soon to a barbed wire fence that they climbed over. Then there was a second such barrier which tore not only Maria’s stockings but also her calves. “Do you see the light flickering in the distance?” asked the old farmer. “Those are of the German border guards lighting their pipes – being changed at 9 p.m.” As they crossed the second barrier into Dutch soil, the old farmer indicated a large tree which was just barely visible to Fritz and Maria in the darkness.

“You see the tree there? My son is waiting there for you.”

With these words, the old H. left my people, turned around, because he did not wish to walk on Dutch soil. Even such people have their principles.

So Fritz and Maria left to reach the tree in high spirits – after all they were in Holland and thus felt safe – and found there a young couple. This couple presented themselves as friends of H. Jr., explaining that he could not come and that they were delegated in his stead. What had happened?

Jr. had received word In the morning that a search was being undertaken for custom smugglers and it was necessary to be very careful; therefore Fritz and Maria would not be safe spending the night at his house.

The young couple would bring them into safety at Heerlen but they were not to speak a word of German, letting only the others speak.

It was good that they had no baggage because even the smallest bag would arouse the curiosity of the police. Maria took the arm of the new Dutch girl friend and Fritz walked gaily with the man to the tram from Keerkrade to Heerlen which they reached at 10 p.m. Isakower waited for them and called me. We are thus again in Holland.

I spent the night telephoning and writing and did not realize that it was already 8 a.m. I had agreed with Dr. van H. that my people should not get off the train at the Central station in Amsterdam because the police made random identity checks there. My dearly beloved travelers were therefore to be met by me at the Amsterdam V.S. station (which is about 10 km before the main station) where they were to arrive at 2:18 [?????]p.m.

At about 8 a.m. my brother Julius called from Paris and declared that Mr. Bohme – who was one of the two gentlemen who had taken over the Vienna factory – had called, and he was totally distressed by the fact that hostage Fritz had flown the coop. Julius should now go to Vienna instead of Fritz, Bohme asked saying that it would be terrible for him because the Gestapo would now arrest him. Julius promised him to inquire with me.

I called Bohme in Vienna then and gave him my word. We had agreed in August that I would turn over the factory without any compensation. I had so agreed because a large part of my family was under the control of the Gestapo. Now this was not the case, but I would keep my word.

I asked him and his companion Bagusat to come to London to sign the contract. This did happen on the 9th of November 1938. I gave them the factory and all the land, material, machines, etc. They agreed to pay me and my family an amount of £400 a month for the next five years. I gave them an amount of £1200 on account of sums received on my London account. After 3 months, in February, 1939, they stopped the payments. I had never received an additional penny.

At 1 p.m. on the 22th of October, I went with my Amsterdam friend Mr. Alfred C. to the railroad station Amsterdam V.S. where we then received the two refugees who looked marvelous and were in best spirits, getting off the train at 1:18 p.m. At 1:55 p.m., we were at the airport at Schiphol where the Silverbird – a Douglas plane with 14 seats – was ready. At exactly 2 o’clock, as agreed with the KLM the day earlier the airplane took off. Over the Channel I unpacked the provisions I had got them. We drank a cooled bottle of champagne to the health of the newly reborn young couple. At 4:00 p.m., we arrived at Liverpool. There, officials of the police and customs were waiting. A half hour later the happy couple was reunited with its even happier family.

Thus ended my efforts at taking our family out of German custody.

I thus had my hands free to continue with the rebuilding of my business reorganisation and to bring my family back into the production process.

N.B.: This translation has been completed on another airflight: Singapore Airlines Inaugural Vienna – Manchester August 23, 1988.