October 3, 2013

Today was our museum and sightseeing day. Still jet-lagged and awake during the night, I managed to fall back asleep and as awakened by a call at 9:45, so we got off to a late start. The breakfast at the Intercontinental is very good. Nathan tried a fried egg this time.

We went up the street to a book store that sold tickets for the Jewish Museum, which is located in several synagogues throughout the area. We went first to the Spanish Synagogue, which has a good exhibit on the history of the Jews of Prague, with emphasis on printed materials and important personalities, as well as the obligatory fantastic display of ritual objects. I’ve spent the past serval years really digging into the family trees of the old Jewish families from Prague, so I recognize the names and faces this time. When I see an engraving of Rabbi Eleazar Flekeles, Dr. Jonas Jeiteles or publisher Wolf Pascheles, I feel I know them. Photography is forbidden, but Nathan secretly takes photos with his i-phone and no one seems to care. Why should they?

We went around the corner to the offices of the Jewish Museum and I asked for Dr. Alexander Putik, the leading expert on Prague Jewish history and author of many important books and articles. His specialty is the political history, figuring out the feuds and fights within the community. Dr. Putik kindly brings us up to the book shop and I proceed to buy a half dozen tomes he suggests, including a brand new edition that records the domicile forms that were filled out by the Jews returning in 1748-1751 after the expulsion by Empress Maria Theresia. A genealogical goldmine if I can manage to link them up to the later trees I have been working on.

Dr. Putik answers my secret wish and offers to take us through the old Jewish cemetery. Ordinarily, visitors are herded through on the far sides of the cemetery, unable to wander through the massive field of jagged stones. But with Dr. Putik we hop over the ropes and follow him to areas we could never otherwise reach. The stones are beautiful, but my Hebrew is not good enough to read them on the fly, and in any case tombstone Hebrew is a real specialty. Nathan and I snap some pictures as Dr. Putik tells us of his recent find, the brother of the Hakham Zevi, a famous chief rabbi of Hamburgi. He cannot remember exactly where all the Nachod (my great-grandmother’s family) graves are, but suspects they are with the Horowitz family (the Nachods are supposedly a branch from one of the daughters of Aaron Meshulam Horowitz) and near the Pinkas synagogue, which was built for them.

Dr. Putik answers my secret wish and offers to take us through the old Jewish cemetery. Ordinarily, visitors are herded through on the far sides of the cemetery, unable to wander through the massive field of jagged stones. But with Dr. Putik we hop over the ropes and follow him to areas we could never otherwise reach. The stones are beautiful, but my Hebrew is not good enough to read them on the fly, and in any case tombstone Hebrew is a real specialty. Nathan and I snap some pictures as Dr. Putik tells us of his recent find, the brother of the Hakham Zevi, a famous chief rabbi of Hamburgi. He cannot remember exactly where all the Nachod (my great-grandmother’s family) graves are, but suspects they are with the Horowitz family (the Nachods are supposedly a branch from one of the daughters of Aaron Meshulam Horowitz) and near the Pinkas synagogue, which was built for them.

After the cemetery, we part from Dr. Putik and make our way through the various exhibits, fabulous displays of Judaica, reproductions and paintings and all sorts of items. An embarrassment of riches. I see a painting of Theresia Wolf (Foges) and immediately know from her maiden name that she is on the family tree. Turns out not too close. She’s my first cousin four times removed’s wife’s first cousin’s wife’s sister. I wish I had scans of all the paintings and photos in the museum. Would keep me busy for the next year.

We stopped into the cafeteria of the Jewish Community to say goodbye and thank you to Dr. Putik (after getting grilled by the guard who claimed he was Hungarian, but sounded and acted Israeli to us). Then we went to the fancier kosher restaurant King Solomon. I finally got my goulasch and knödel. A bit disappointing. Not quite enough meat and the knödel were too dry. Nathan ordered and ate goose (hard to believe).

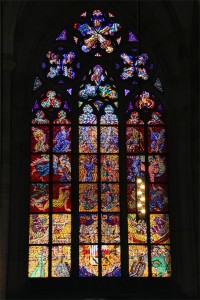

After lunch we walked down across the river and found our way up to the big castle (apparently the largest in Europe by some measures). Nathan and I really liked exploring all the sights. We entered the big church of St. Vitus with it’s fantastic stained glass windows (glass is a Bohemian specialty). The exterior is not too different from Notre Dame in Paris. We had the most fun in a museum full of armor and weapons, many of then 500-1,000 years old. Nathan got to try his hand at shooting a cross-bow. I thought the old viking swords were cool.

After lunch we walked down across the river and found our way up to the big castle (apparently the largest in Europe by some measures). Nathan and I really liked exploring all the sights. We entered the big church of St. Vitus with it’s fantastic stained glass windows (glass is a Bohemian specialty). The exterior is not too different from Notre Dame in Paris. We had the most fun in a museum full of armor and weapons, many of then 500-1,000 years old. Nathan got to try his hand at shooting a cross-bow. I thought the old viking swords were cool.

At the bottom of the castle we even went into a torture chamber. Nathan was intrigued by a contraption that looked like it was used to lower a person into a pit with wild animals. We also visited the Lobkowicz Palace, which has an audio guide spoken by the current head of the Lobkowicz family (an American). The family had fled the Nazis and returned, only to have their property confiscated again by the Communists. They managed to recover the palace and its contents, mostly family paintings but also a nice Breughel landscape and some Canalettos from London, after the end of Communism in 1989.

Restitution in the Czech Republic is a sticky subject. As is history. After the nationalism, nazism and communism of the 20th century, basically no one in the country knows anymore what the truth really is. The country is filled with legends of the Bohemian roots of the place, mostly neglecting the German and Jewish contributions. For example, you’ll often hear that Jews lived in the area since about the 10th century. What they don’t say is that the 10th century is also the earliest evidence of a separate Czech language in the region, and that Czechs arrived maybe a few centuries earlier. The German presence probably predated them. But the land was ethnically cleansed (twice) in the last century with the extermination of the Jews and the subsequent expulsion of millions of Germans. So today it is basically all Czech all the time.

When people debate about Israel and whether it should have a one-state or two-state solution, I like to remind them of the Czech Republic. I don’t remember hearing about any recent UN resolutions concerning the expelled Germans. And no one seems to care about all the expropriated Jewish property in the country, most of it never returned.

For example, the castle outside Prague that was owned by Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer (of Klimt painting fame) was taken and used as the home of the Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia Reinhard Heydrich (the man who convened the Wannsee Conference and set in motion the Final Solution). After the war, the Communists expropriated the castle again. When the Communists fell, the Czechs privatized the castle, selling it to an agricultural company, before they enacted any restitution laws. Ferdinand’s heirs at law, including his niece Maria, did not even qualify for a token restitution payment (limited to victims and their children only).

I am dealing with a crazy case at the moment. I am helping out the family of a holocaust survivor, a woman who made it through Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and several other camps. She returned to her home in Moravia and managed to reclaim the property of her murdered sister’s murdered husband Rabbi Schön, including an old illuminated manuscript called a Kitzur Mawar Jabok, with prayers for the dead, that had apparently come from the community of Mikulov (Nikolsburg).

She managed to escape from Czechoslocakia and came to the United States. After she died, her family offered to sell the book to the Jewish Musuem of Prague, which initially agreed to purchase it. But then, with the assistance of the Holocaust Claims Processing Office in New York, the Musuem and the Federation of Jewish Communities in the Czech Republic claimed ownership of the book. I find the claim incredible. First, no one knows for sure who owned the book before the war, nor how the book made its way into the hands of the Holocaust survivor, so calling the book “stolen” is a leap. Second, the Museum and the Federation were not the prior owners of the book. Their theory is that the book should have been stolen by the Nazi, then stolen by the Communists, and in the 1990s should have been given to the Federation and housed in the Museum. That’s not exactly a convincing claim of title in my opinion. I tried to set up a meeting while I was here, but the Museum directed me to its lawyer in New York, who only wrote me this Monday. So we’ll have to see how this gets resolved. I did see another book on display today and have to agree that this one is much better. So now I know why they want it. I’m ordinarily on the other side of these cases, seeking restitution. But in my book, before you go accusing a Holocaust survivor of holding stolen property, you’d better have some real proof that it was stolen and a good claim of title.

A postscript to yesterday’s trip to Theresienstadt. I remembered the story that the survivor Pavel Stransky told his tour. He had returned at the end of the war to Theresienstadt, but was caught in the quarantine because of the typhus epidemic. His new id card said “suspect of typhus” so an attempt at escape was impossible. He and a friend then doctored their id cards to say “unsuspect of typhus” and were able to convince a guard that they could leave. Then, when a Russian soldier tried to commandeer their truck, they claimed to have been exposed to typhus in order to scare him off. I contacted a survivor friend about Stransky, thinking that they must know each other, but apparently he had a bad experience with him when they were in Auschwitz. I suppose there are folks I knew in high school that I might not want to see either, and my high school was not the worst hell on earth, as his was. So I can understand.

Tomorrow I have a meeting at the new Jewish cemetery to discuss making the database available to genealogists. Then I have lunch with my old friend Julius Mueller and new Ckyne friend Heleen Sittig. In the evening, we will be eating with my cousin Michaela and her family. Then Saturday is the big trip down to Ckyne for the rededication. So far, it has been a wonderful trip.