In German, the phrase used for wishful thinking is Der Wunsch ist Vater des Gedankens, which translates as “the wish is father of the idea.” I like that construction because I think it says a lot about how we decide what we believe.

This week’s testimony by Dr. Christine Blasey-Ford and Judge Brett Kavanaugh before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee has the entire country talking about sexual assault and alcohol use, but also about more abstract issues of memory and evidence and proof. Understandably, given the political setting, the debate has divided cleanly along partisan lines, but in doing so, it has sometimes placed people in unfamiliar territory on some of the more broad themes. I include myself.

I am generally very defense-oriented, and a firm believer in giving accused defendants the benefit of reasonable doubt. Forcing the state to overcome a high burden of proof undoubtedly leaves many crimes un-prosecuted and allows many guilty defendants to avoid conviction, but it also feels to me a necessary barrier to avoid wrongful prosecution of the innocent. It is the fair price we agree to pay when we give the state the authority to punish the guilty.

This willingness to entertain the possibility of reasonable doubt has led me to some unpopular decisions. When I was a juror in a gang murder case back in 1994, we deliberated for less than an hour before taking our first vote, 11-1 for guilty. Guess who the holdout was? After three days, about half the jurors ended up agreeing with me but the jury was hung. The defendant was retried and convicted and twenty-four years later he is still in prison. It bothers me to this day, especially because I am convinced not only that the state had not met its burden of proof, but that the defendant was actually innocent of the charges against him. As I wrote a few years ago when referring the case to the Innocence Project:

He should have been found not guilty, but we hung. Instead he was re-tried and sentenced to 35 years to life. The prosecution used all of the exculpatory evidence against him by ridiculous “expert” testimony. So, for example, the fact that just minutes after the murder he was apprehended separate and apart from the group of kids carrying the murder weapon was “proof” that he was guilty because gang members “always” hand off the gun to someone else to evade prosecution. The fact that he had no gunshot residue on him was proof of his guilt, because gang members know how to wipe off residue to make it seem like they are innocent. The fact that his prints were not on the gun was proof that he was guilty because gang members know to wipe off the gun to avoid fingerprinting. The fact that the main eyewitness at first did not identify him as the shooter, and only changed his testimony upon re-questioning a day later, was proof that he was guilty, because the witness was obviously too intimidated and scared to identify him the first time. Etc. Etc. The truth almost certainly is the guy didn’t do it. They later found the guys who had been running away with the murder weapon, but by that time the police (Rampart division, I think) had pinned the murder on [the defendant] and persuaded the witnesses to identify him, and so they just left it at that. His girlfriend (mother of his 1 year old child) testified for him in the first trial, but didn’t the second time because in the meantime they had prosecuted her for jury tampering for supposedly approaching a juror on my panel and telling her that he was innocent and they knew who did it.

Do I know for sure that the defendant wasn’t the one who shot the victim in his stomach with a shotgun when he refused to hand over his wallet? No, I don’t. But it didn’t seem very likely to me. Could he have been another one of the kids who surrounded the victim and therefore been guilty of aiding and abetting the crime? Absolutely yes, and I might have even convicted him of that had the prosecutors bothered even to charge him with aiding and abetting, which they did not, probably because the detectives had gotten the main eye-witness, who had been robbed by the gang a minute earlier, to change his story and say that the defendant was the one with the shotgun.

So I am a bleeding heart liberal. Ok then, here’s another one. I was never convinced that George Zimmerman was guilty of murdering Treyvon Martin. Martin was the poor kid just returning from a convenience store, who got killed by Zimmerman, a vigilante patrolling his neighborhood. Why did I have reasonable doubts that Zimmerman was guilty? Because there was good evidence that Martin had been beating up Zimmerman before he was shot. Quoting from the summary on Wikipedia, which comports with what I recall. “The police officers observed that Zimmerman’s back was wet and covered with grass, and he was bleeding from the nose and the back of his head. . . . The only eyewitness to the end of the confrontation stated that Martin was on top of Zimmerman and punching him, while Zimmerman was yelling for help. This witness stated that “the guy on the bottom, who had a red sweater on, was yelling to me, ‘Help! Help!’ and I told him to stop, and I was calling 911.” Zimmerman may have provoked the altercation, but Martin’s friend, who was on the phone with him at the time it began, stated that it was Martin who first said to Zimmerman “What are you following me for?” The witness testimony and the observed injuries makes it hard for me to conclude beyond any reasonable doubt that Zimmerman could not use the defense of self-defense.

Ok, so my bleeding heart always goes in favor of the defendant no matter who he is. So, what do I think about Judge Kavanaugh? Here was my initial response on Facebook:

I believe Kavanaugh is lying. He is lying to himself and to us about who he was and is. It is 100% believable that Dr. Ford attended one of those small gatherings with his beer-drinking buddies that Kavanaugh recorded on his calendar (July 1 and August 7 seem the most likely candidates). It is perfectly believable that she was there and left early after an incident. It is absolutely believable that Kavanaugh and Judge might have rough-housed and acted out an attempted rape with her while she was at the party. (I can remain agnostic on whether they intended to go through with it if they had not been interrupted.) And it is certainly believable that for Kavanaugh and Judge the party went on and no part of the evening was memorable to him. Finally, it is absolutely believable that Ford would have remembered the event and been traumatized as she was.

What is also 100% certain is that Kavanaugh is purposely lying about the state of the evidence, which he as a judge knows perfectly well how to assess. It is absolutely NOT true, as Kavanaugh claimed over and over again, that “all four of the witnesses said it did not happen.” Saying they have no recollection is NOT the same, as Kavanaugh certainly knows, as saying that something did not happen.

Asking if Kavanaugh remembers not remembering something after drinking, as so many Senators tried to do, is stupid. What they should have asked is what he remembers of those parties and if it is possible — possible! — that he might not today remember something that happened that was absolutely untraumatic for him.

Kavanaugh is most likely purposely lying about the meaning of his yearbook page (Boof, Renate Alumnius, Devil’s Triangle, FFFF, etc.), and it was notable that he would not readily admit that his calendar note about “skis” meant beers (as in the slang term brewskis).

It is Kavanaugh’s CURRENT lying, to himself and to us, that should bother people about his nomination (beyond all of the rest of the political implications of his judicial views).

If I were a Senator, I would very easily vote no on his confirmation. This is not what we want in a Supreme Court Justice (nor in a President).

[For a more thorough discussion of Kavanaugh’s lies and dissembling during his testimony see this excellent article by Nathan J. Robinson in Current Affairs.] As I began reading the comments of others, I noticed that many Kavanaugh supporters were arguing that he was innocent or should be presumed innocent, or that the evidence was insufficient to find that he had assaulted Dr. Blasey-Ford. I hadn’t focused so much on the issue of innocence or guilt because, after all, this is not a criminal trial but rather a confirmation proceeding. What matters is not his past, but his present character. Guilt beyond a reasonable doubt really shouldn’t be an issue at all. But of course it is. And then I started thinking about whether the evidence so far would be sufficient to convict Judge Kavanaugh of a sexual assault against Dr. Blasey-Ford. I think it would.

I have heard people say there is “no evidence” to prove that she was assaulted. That is simply false, because of course testimonial evidence is evidence. Here is the California jury instruction on direct and indirect evidence:

Evidence can come in many forms. It can be testimony about what someone saw or heard or smelled. It can be an exhibit admitted into evidence. It can be someone’s opinion. Direct evidence can prove a fact by itself. For example, if a witness testifies she saw a jet plane flying across the sky, that testimony is direct evidence that a plane few across the sky. Some evidence proves a fact indirectly. For example, a witness testifies that he saw only the white trail that jet planes often leave. This indirect evidence is sometimes referred to as “circumstantial evidence.” In either instance, the witness’s testimony is evidence that a jet plane few across the sky. As far as the law is concerned, it makes no difference whether evidence is direct or indirect. You may choose to believe or disbelieve either kind. Whether it is direct or indirect, you should give every piece of evidence whatever weight you think it deserves.

Dr. Blasey-Ford gave testimony that would clearly be sufficient to prove a sexual assault.

In the summer of 1982, like most summers, I spent most every day at the Columbia Country Club in Chevy Chase, Maryland, swimming and practicing diving. One evening that summer, after a day of diving at the club, I attended a small gathering at a house in the Bethesda area. There were four boys I remember specifically being there: Brett Kavanaugh, Mark Judge, a boy named P.J., and one other boy whose name I cannot recall. I also remember my friend Leland attending. I do not remember all of the details of how that gathering came together, but like many that summer, it was almost surely a spur-of-the-moment gathering. I truly wish I could be more helpful with more detailed answers to all of the questions that have and will be asked about how I got to the party and where it took place and so forth. I don’t have all the answers, and I don’t remember as much as I would like to. But the details that — about that night that bring me here today are the ones I will never forget. They have been seared into my memory, and have haunted me episodically as an adult.

When I got to the small gathering, people were drinking beer in a small living room/family room-type area on the first floor of the house. I drank one beer. Brett and Mark were visibly drunk. Early in the evening, I went up a very narrow set of stairs leading from the living room to a second floor to use the restroom. When I got to the top of the stairs, I was pushed from behind into a bedroom across from the bathroom. I couldn’t see who pushed me. Brett and Mark came into the bedroom and locked the door behind them. There was music playing in the bedroom. It was turned up louder by either Brett or Mark once we were in the room.

I was pushed onto the bed, and Brett got on top of me. He began running his hands over my body and grinding into me. I yelled, hoping that someone downstairs might hear me, and I tried to get away from him, but his weight was heavy. Brett groped me and tried to take off my clothes. He had a hard time, because he was very inebriated, and because I was wearing a one-piece bathing suit underneath my clothing. I believed he was going to rape me.

I tried to yell for help. When I did, Brett put his hand over my mouth to stop me from yelling. This is what terrified me the most, and has had the most lasting impact on my life. It was hard for me to breathe, and I thought that Brett was accidentally going to kill me. Both Brett and Mark were drunkenly laughing during the attack. They seemed to be having a very good time. Mark seemed ambivalent, at times urging Brett on and at times telling him to stop. A couple of times, I made eye contact with Mark and thought he might try to help me, but he did not.

During this assault, Mark came over and jumped on the bed twice while Brett was on top of me. And the last time that he did this, we toppled over and Brett was no longer on top of me. I was able to get up and run out of the room. Directly across from the bedroom was a small bathroom. I ran inside the bathroom and locked the door. I waited until I heard Brett and Mark leave the bedroom, laughing and loudly walk down the narrow stairway, pinballing off the walls on the way down. I waited, and when I did not hear them come back up the stairs, I left the bathroom, went down the same stairwell through the living room, and left the house. I remember being on the street and feeling this enormous sense of relief that I had escaped that house and that Brett and Mark were not coming outside after me.

A conviction based on this testimony alone would never be reversed for insufficiency of the evidence. There are thousands, perhaps millions of people in jail today based on no more convincing evidence than this. So, the first question to ask yourself is, if you knew nothing more than this one statement, would you find that Judge Kavanaugh is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt? If you find yourself saying no, you aren’t following the instructions. How do I know? Because I told you to assume you knew nothing other than her testimony. In order to cast doubt, you need to look outside her testimony, to your own experience and to other things you know about the matter. And here is where we get back to the original theme of this blog — wishful thinking. Where your mind wanders, how hard it looks for a basis for doubting her testimony, is all about you.

This type of purposeful intentionality is inherent whenever we weigh evidence, and it is why I was very disappointed with Judge Kavanaugh’s initial Senate testimony before the present controversy. Perhaps he was the only student at Yale Law School who didn’t receive the notoriously theoretical training that Yale was best known for at that time, or perhaps he had a few too many beers along the way, but as a person who has been a judge for twelve years on the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, he certainly must know that judges do more than just “call balls and strikes,” as Chief Justice John Roberts famously said at his 2005 confirmation hearing. (Kavanaugh said: “A good judge must be an umpire, a neutral and impartial arbiter who favors no litigant or policy.”) Investigating, assembling, arguing and deciding legal and factual issues all require creativity and ideas, and, as the German saying goes, the father of those ideas is the wish, the result you want to achieve. When you have no real desire for one or the other side to win, it is easy to think of judging as just calling balls and strikes (although also baseball umpiring is more complicated than it may seem). But when you are deciding issues where you really do care about the result, it is not so easy to make sure that your wish is not controlling the way your mind is working. You have to try to sublimate that wish to another wish (for example, a commitment to stare decisis).

Back now to the evidence against Judge Kavanaugh. We started with her testimony, which by itself is sufficient for a conviction. The next question is whether there is any contrary evidence, or any other reason to doubt her testimony. In a criminal case, the proof standard is explained as follows in a California jury instruction:

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is proof that leaves you with an abiding conviction that the charge is true. The evidence need not eliminate all possible doubt because everything in life is open to some possible or imaginary doubt.

Many arguments have been made against Dr. Blasey-Ford’s allegation, but they all can be judged by this reasonable doubt standard. Reasonable doubt is not just any possible doubt. Anyone can come up with possible scenarios. You have to have a reason to believe the scenario is true.

Having already dispensed with the “no evidence” argument, here are a few of the others. Whether or not you even consider these arguments is already an example of “wishful thinking,” and I admit that some of them did not occur to me, notwithstanding my defense-oriented bias, perhaps because my dislike of Kavanaugh’s political and judicial views made me less inclined to want to find them.

- Judge Kavanaugh has a “sterling record of public service.” It is true that Judge Kavanaugh is incredibly accomplished. An excellent student at top schools, clerkship, government service, over a decade on the court of appeals. On paper, he is absolutely a good candidate for the Supreme Court. Of course, he has not avoided all controversy, whether as a member of the Kenneth Starr Special Counsel investigating President Clinton or as a member of the Bush Administration. At his initial conformation hearing, there were already allegations that he had lied previously about receiving stolen democratic strategy memos. But leaving those aside, his record is strong. Does this make it less likely that the allegations are true? That is a different question. Kavanaugh certainly wouldn’t be the first person in a prominent position to be brought down by a shocking revelation of past improprieties. It would be hard to say that this factor alone would raise reasonable doubts about the veracity of Dr. Blasey-Ford’s allegation.

- No one else has ever accused him. While perhaps true before Dr. Blasey-Ford’s accusation was public, it is no longer true. At least two others have now accused Judge Kavanaugh of sexual assault. I can agree that the number of accusations against a person does have an impact on how we view an accusation. I don’t have any scientific evidence, but it does feel right that people who do wrong things continue to do them. But this argument isn’t as helpful as it seems. Someone has to be the first to make a public accusation. Then you need to wait to see how many others come forward. There needs to be more time to investigate. That process has hardly begun and it is unclear if the FBI or journalists will be looking to interview others who might have had similar experiences. Time will tell, but it is still very early. I would say it is far too early to say that there is reasonable doubt about Dr. Blasey-Ford’s accusation merely because she is the first to go public.

- She waited too long to tell anyone. This argument is an interesting one, but I think it may be a bit too early to judge it. Dr. Blasey-Ford hasn’t said that she told no one about the event. She said she did tell a few friend and her husband. Her friend at the time Leland Ingham Keyser had her lawyer submit a statement saying “Simply put, Ms. Keyser does not know Mr. Kavanaugh and she has no recollection of ever being at a party or gathering where he was present, with, or without, Dr. Ford.” We’ll have to see if anyone else remembers Blasey-Ford talking about the attack or identifying her attacker. Apparently she did tell her therapist about the attack six years ago, at least that is what has been alleged. But does the length of time before speaking out make her allegation less reliable? It is quite common, perhaps even more common, for people to keep secret an incident of sexual assault. As a result, one could even make the argument that Dr. Blasey-Ford’s allegation is more reliable because she waited so long. The fact that the length of time argument can cut both ways makes it a poor one to rely on in deciding whether there is reasonable doubt. Certainly there are a number of examples of belated accusations being believed despite the delay. Bill Cosby was recently sent to prison as a result of previously unreported assaults from 2004. The timing factor alone cannot answer whether the accusations can be believed beyond a reasonable doubt. You might ask yourself, having initially kept the attack from her parents for fear of being punished for going to the party in the first place, what incentive would Dr. Blasey-Ford have had to later tell the story or identify her attacker? It may not help her accusation that there are no more contemporaneous reports of the attack, but acting in a normal and reasonable way should not make her later revelation unreasonable.

- No one else can confirm her story. Again this is something that is true with many sexual assault allegations. Based on her story, what type of confirmation would you expect to have? From whom did you want confirmation? Her attackers? Really, this is a variation on the “she didn’t tell anyone soon enough” argument.

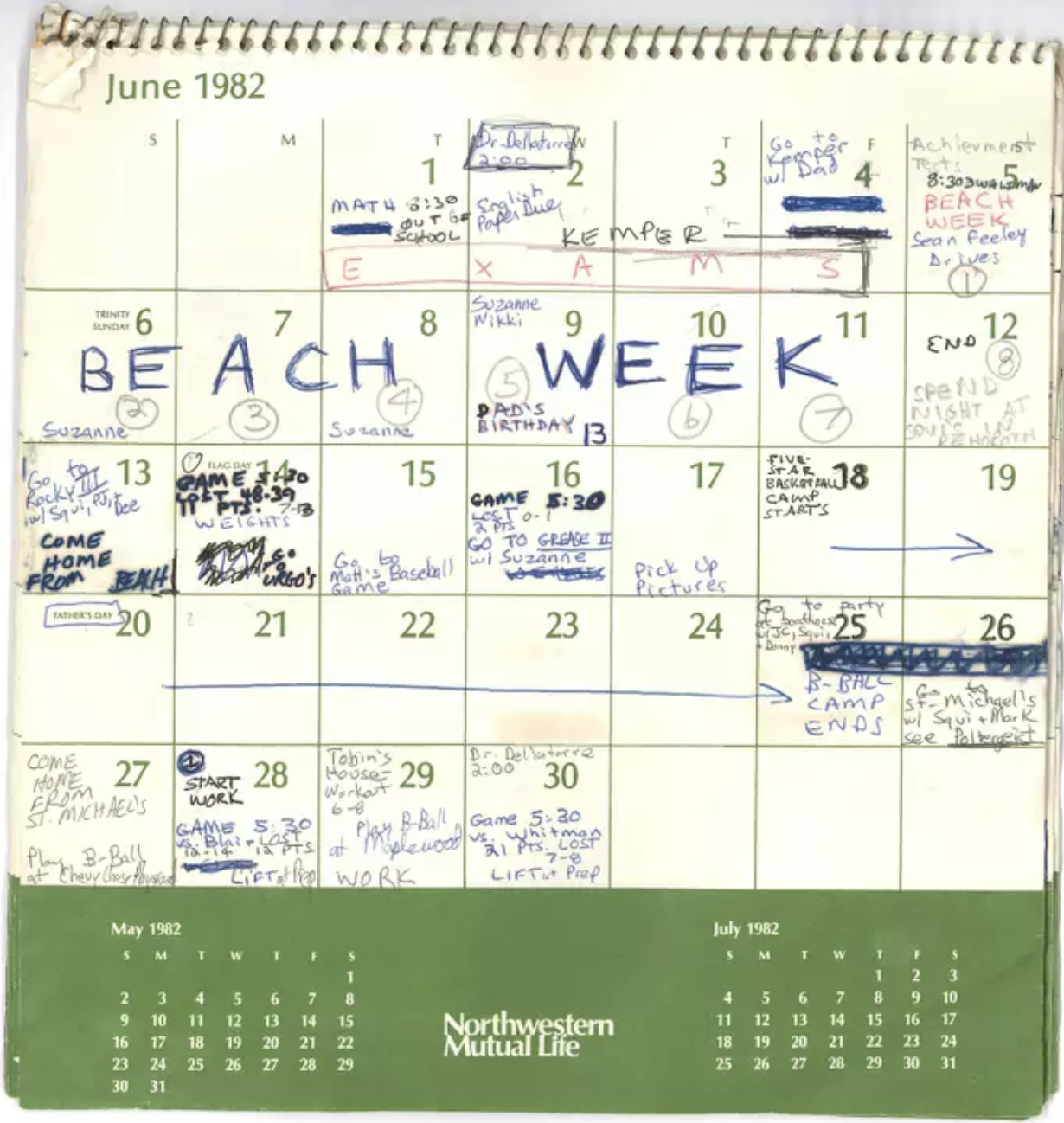

- There is no corroborating evidence. This one is really not true. Amazingly, Judge Kavanaugh produced a calendar from 1982. Actually it is more of a diary. Kavanaugh recorded events, even parties, often after the fact. At least one of the parties, on Thursday, July 1, 1982, is memorialized with the note: “Go to Timmy’s for skis w/ Judge, Tom, PJ, Bernie, Squi.” This note appears to refer to a small beer (ski = “brewski”) party with a few of Kavanaugh’s friends, two of whom (Mark Judge and PJ) were also identified by Blasey-Ford as potential witnesses before Kavanaugh’s diary became public. Another party on Saturday August 7 says “Go to Becky’s, Matt, Denise, Laurie, Jenny Hail.” So it is obviously true that Kavanaugh and his friends occasionally got together that summer in smaller parties like the one Blasey-Ford described. Kavanaugh himself has admitted that he often drank beer with his friends. (“Yes, we drank beer. My friends and I, the boys and girls. Yes, we drank beer. I liked beer. Still like beer. We drank beer.”) The calendar certainly does corroborate certain aspects of the story, and may even document the party in question.

- The other witnesses deny that it happened. Again, this one is not true. Yes, the two accused assaulters, Kavanaugh and Mark Judge have both denied attacking Blasey-Ford, which is certainly not at all unusual. But Kavanaugh mischaracterized the evidence from the other witnesses during his testimony. Leland Keyser’s attorney’s statement simply said she did not remember and does not know Kavanaugh. That she did not remember anything is hardly remarkable. Blasey-Ford did not say Keyser had witnessed the attack, only that she had been at the party. (“Oh no, she didn’t know about the event. She was downstairs during the event and I did not share it with her.”) The statement that she does not know Kavanaugh means only that she doesn’t know him now, not that she never attended a party with him when she was a teenager. Kavanaugh himself admitted as much. (“I — I know of her. And it — it’s possible I, you know, saw — met her in high school at some point at some event. Yes, I know — I know of her and, again, I don’t want to rule out having crossed paths with her in high school.”) PJ Smyth’s response was similarly non-committal. (“I am issuing this statement today to make it clear to all involved that I have no knowledge of the party in question; nor do I have any knowledge of the allegations of improper conduct she has leveled against Brett Kavanaugh.”) The truth is that it would be absolutely remarkable if any of the other attendees, including Kavanaugh and Judge, remembered that party or the attack on Blasey-Ford. The incident Blasey-Ford described was a very brief encounter. It was likely not at all memorable to Kavanaugh and Judge, who were allegedly inebriated at the time. None of the other attendees at the party were even made aware of the attack. There is no reason to believe any of the other attendees would have any recollection at all of a small high school party thirty-six years ago. Given the circumstances, I would view with great suspicion any witness who would do anything other than say they don’t recall.

- She doesn’t remember when and where it happened. True, she cannot remember where exactly the attack occurred, nor on what date it occurred. That she cannot remember the date seems unremarkable. I can remember a few infamous parties from high school, but could not begin to remember the date. On the other hand, I do remember the location of some of those parties, the ones where I knew the person who lived in the home. (For example, the infamous party at the Familian house on Stone Canyon in Bel Air, or a party at Ben Peck’s house in Pasadena or San Marino with an enormous dance hall.) I cannot remember the location of the parties where I did not know the person whose home it was. (For example, the afterparty for the Marlborough prom, the first time I became drunk and the first time I kissed a girl.) That she cannot remember the location might mean only that she did not know the person whose house it was. This is consistent with the contention of Judge Kavanaugh that Blasey-Ford was not part of his immediate social circle, and would explain why they never ran into each other again afterwards.

- People make up allegations, especially against famous people. This seems to be true. The issue is whether the mere fact that an allegation is made against a famous person is a reason to harbor reasonable doubt. In that sense, the argument is similar to the first argument about Kavanaugh’s “sterling record.” There are also numerous instances of allegations against famous people that are found to be true. One key fact here is when Blasey-Ford first complained. If it is true, as the notes from her therapist and the statement of her husband suggest, that she first made the allegations six years ago, when Kavanaugh was just a Circuit Court judge, that certainly bolsters her credibility. Further, if it is true that she first reached out to the Senate and the Washington Post when Kavanaugh was mentioned as a possible nominee, but before the actual nomination, that also would be inconsistent with someone who simply made up a story about a famous person. Prior to the actual nomination, Kavanaugh was hardly a household name.

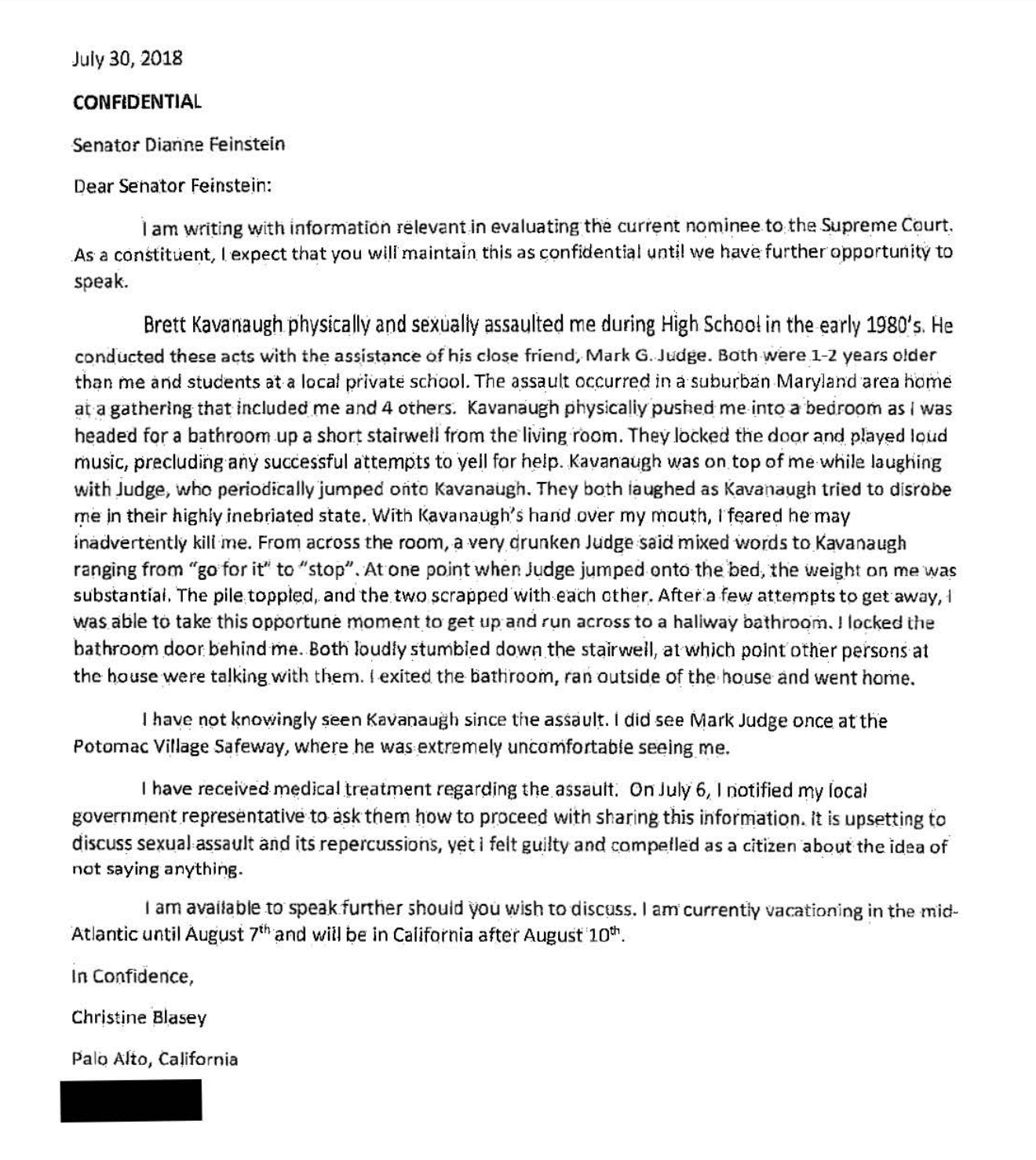

- The Democrats are out to get him. This is certainly true, but not necessarily relevant to assessing the credibility of Blasey-Ford’s allegation, which seems to have been made independent of any organized opposition to Donald Trump and the Republican party. Senator Lindsay Graham’s finger-pointing fulminations against Democrats at the hearing were an obvious case of projecting from his own self-loathing. Does he really feel so virtuous for voting in favor of Justice Sotomayor in 2009 when the Republicans held just 40 seats in the Senate and had no way to stop her? Or Justice Kagan in 2010 when they had just 41? Were either of them accused of sexual assault or any other improprieties? Yes, Democrats do not want Kavanaugh on the Supreme Court. But Republicans didn’t want Merrick Garland on the Supreme Court. If anything broke the famed collegiality of the Senate, it was the unprecedented decision of the entire Republican majority to stand by and support Mitch McConnell’s decision to block Garland’s nomination by refusing to even entertain it. If Senator Graham wants to blame someone for a lack of bipartisanship, he should look in the mirror. But in my view partisanship is merely honesty. What is dishonest is pretending that you are non-partisan, for denying that the wish is the father of the idea. As for this case, the facts are that Blasey-Ford repeatedly contacted and then spoke with her congresswoman Anna Eshoo before sending a letter to Senator Dianne Feinstein on July 30, 2018. Absent some evidence that the allegations were not her own, or that Eshoo or her staff encouraged Blasey-Ford to embellish them, this argument seems to be more of a paranoid fantasy than an argument about reasonable doubt. There would have to be some more evidence of collusion before this argument could be considered. Blasey-Ford’s testimony gave no indication that it was manufactured by any third party.

- Someone leaked her allegation just to stop his confirmation. This may be true, but it is not an argument against the veracity of her claim, especially since there is no indication that Blasey-Ford, who had requested confidentiality, was the one who leaked them. If the allegations had been leaked only after the Senate approved Kavanaugh, would that make a difference? I don’t think so. I find it interesting that those who are so ready to believe Kavanaugh’s denials have such a hard time believing Senator Feinstein’s statement that she and her staff did not leak the information. (The Intercept reporter who broke the story, Ryan Glim, confirmed that Feinstein and her staff did not leak to him.) It makes perfect sense to me that Senator Feinstein would keep the woman’s allegations a secret after being told that Blasey-Ford did not want to come forward publicly. If she had done otherwise, she could have been correctly criticized for breaking confidentiality. She could not have known in advance that Blasey-Ford would agree to come forward after the story broke, or that she would be such an excellent witness in her testimony. Whoever is responsible, it seems likely that the leak was motivated by a desire to keep Kavanaugh off the court, but there again the timing makes sense because the leaker would have wanted to wait to see if perhaps something else first derailed the nomination. In any case, don’t kill the messenger. It’s the message we are assessing, not who first told us about it.

- Senator Feinstein recommended her lawyer. Apparently one of the lawyers, Debra Katz, was recommended by Feinstein’s office. She is clearly an opponent of President Trump and the Republican party. I suppose some people might find the allegations less credible because they don’t like Blasey-Ford’s attorney, but that would only reflect their own bias, not an objective evaluation of the evidence.

- Dr. Blasey-Ford behaved badly in high school and college. Again this may be true, but it is not clear to me how this is relevant to her allegations. In fact, it seems to me more consistent with her admission that she attended a party with boys and drank beer at age 15 without her parents knowing. She also testified that the incident left her with emotional problems, which is also consistent with later poor choices. But besides the slut-shaming aspects of this argument, I don’t see how it makes her allegations any less convincing. If demeanor at the Senate hearing is any indication, she has matured, arguably more than Kavanaugh has.

- She flies on airplanes but says she is afraid of flying. Faced with Kavanaugh’s numerous lies and half-truths, his supporters have grasped at straws to try to show that Blasey-Ford is untruthful. She said she is afraid of flying, yet she has flown on airplanes. Ok. That doesn’t seem too remarkable, nor does it seem to reflect poorly on her credibility.

I would characterize all of the arguments above as wishful thinking, an attempt to raise reasonable doubt from mere possible doubt. Most of the points are equivocal at best. If a witness said he saw a red mustang, would you find him less credible if I told you that most mustangs are black, not red? If a fact or argument could be at the same time either consistent or inconsistent with the allegation, it really doesn’t have any bearing on credibility.

I might feel differently about the evidence produced so far if I were looking at it as a partisan for Judge Kavanaugh. My mind would be actively searching for reasons to doubt Blasey-Ford’s account. Otherwise unremarkable facts or potential discrepancies might loom large. That is natural, I think. It is how we all judge and make decisions. But it doesn’t make those decisions correct. I am having trouble finding any of the purported reasons to doubt her testimony to be at all relevant or persuasive.

Part of the discomfort with Blasey-Ford’s allegation is the fear that anyone could be falsely accused after a long period and be unable to disprove the allegations. This is certainly true. For this reason, we have statutes of limitations, which are the result of policy decisions that it is better to encourage people to come forward with claims in a timely fashion, even if it means that some truthful claims that are brought too late might go unheard. Sometimes there is good reason not to have a limitations period or to extend it. I don’t think I would have a problem if the law were to say that Blasey-Ford’s allegations are too late to be actionable, either in a criminal or civil case. For me, it is not so much the truth of the allegations, but Kavanaugh’s response that is so unnerving.

I’ve seen Senator Jeff Flake say that Kavanaugh’s angry, rude and dissembling testimony is understandable, and that if he were unjustly accused, he might act the same way. The problem with that argument is that the bad behavior also fits if the accusations are true. As others have pointed out, there are numerous instances of famous people first issuing angry, convincing denials of allegations that later turned out to be true. Indeed, Kavanaugh spent a good deal of his early career prosecuting President Clinton for just that type of offense.

Really there are only a few scenarios that are possible here: (1) It happened and Kavanaugh doesn’t remember; (2) it happened and Kavanaugh does remember; (3) it didn’t happen and Kavanaugh doesn’t remember; and (4) it didn’t happen and Kavanaugh does remember.

It happened and Kavanaugh doesn’t remember. The first scenario seems to me the most likely scenario given the evidence so far. She remembers because it was traumatic for her. He doesn’t because it didn’t mean anything to him. I can give a parallel example from my own experience. When I was seventeen years old I qualified for the National Forensic League tournament in San Antonio, Texas. Because my partner and I lost in the district semifinals in oxford two-man debate (another outrage story for another day) I had to try student congress, which I was able to win at the district level to qualify for nationals. The national tournament consisted of three days of student congress, held in a small classroom with about thirty other students. To win an award, you had to do well all three days, which meant speaking as much as possible and impressing the judges. One of the other contestants in my room was Neal Gorsuch from Georgetown Prep. He was just sixteen but already an insufferable blow-hard, eager to impress with meaningless interjections of “points of personal privilege” and bragging references to his beltway connections. I and the other ex-debaters in the event, some of whom I had known from tournaments and the summer Georgetown Debate Institute, saw him as ridiculous. But the less worldly competitors, from smaller rural districts, thought he was just the cat’s meow. On the second day of the competition, Gorsuch was elected the speaker, a position that did not allow him to make speeches, but gave him the gavel and the ability to choose who would speak. I raised my hand the entire day, every time, and he never called on me to speak. It was clearly on purpose. I vaguely remember complaining near the end of the day, but the judges were inexperienced, and did not realize that what Gorsuch was doing was not permitted. I ended the day without getting a chance to speak, meaning that I received zero points and was out of competition for an award, which was obviously what Gorsuch intended. I returned to our hotel on the river walk and sulked. I remember sitting at a table with my friend Brian Lee by the pool. Up walked another boy who asked me if I was going to Princeton in the fall because he was too. I said yes and asked how he knew? “My friend Neal told me,” he said, pointing to Neal swimming in the pool. My instant response: “Neal is the biggest asshole I have ever met. If you are his friend, you must be one too and I don’t want to talk to you.” The boy walked away and rejoined Neal in the pool, letting him know what just happened. Can you guess how the story ends? Well first, Neal won the tournament, rubbing salt into my wounds. I remember only having the satisfaction of giving a scathing attack on Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative on the third day where I pointed out that the other students didn’t even know where the word laser came from. Two months later I got a call from one of my new roommates, Robert Glucksman. We talked for a while and I learned he was from Bethesda, and also had been at the nationals in San Antonio (in Lincoln-Douglas debate). After I hung up I had a bad feeling in my stomach. Could he have been the one? Sure enough, I arrived at Princeton at the end of the summer (the day of the 1984 US Open finals — McEnroe over Lendl, which my dad stayed in New York to see while my mom dropped me off) and there he was, my new bunkmate Rob, the one guy in the whole world I had told off without any good reason on the day that Neal Gorsuch cheated me out of the national tournament. It turned out that Rob and I in fact did not get along well at all (having nothing to do with what happened at Nationals). But the story is one I have often retold. Thirty-four years later, I’d be happy to testify about it. But I bet Neal Gorsuch, now sitting on the Supreme Court thanks to an eerily similar act of dishonesty by Senator Mitch McConnell, wouldn’t remember at all how he cheated against me to win. As a coda, I can very well imagine how Blasey-Ford felt when she heard the name of her tormentor being discussed as a possible Supreme court pick. When I heard on the radio that Gorsuch was the nominee, I was driving on the freeway on my way down to USC to teach my Art Law class. I screamed at the top of my lungs. At the very least, I know exactly what it feels like to learn that the Georgetown Prep teenager who wronged you in high school has been nominated to sit on the highest court in the land. Blasey-Ford and I have that much in common.

I have to say that I also feel I have a lot in common with Judge Kavanaugh, or at least am very familiar with his type. I also went to a small all-boys college prep high school (Harvard School) where football was a big deal. (Luckily my debate partner was also an offensive lineman, so I was a bit protected.) Kavanaugh’s parents were a lawyer and judge. Mine were a judge and a college professor. Like Kavanaugh, I went to a top Ivy League (Princeton) school and then on to law school. I’ve gone to school with more than my share of people like Kavanaugh. I remember an incident at Princeton, the morning after the first Reagan-Mondale debates, which was objectively a disaster for Reagan. I sat down with a couple of other students of the more, shall we say “athletic” persuasion, and began disparaging Reagan. After a few exchanges one of them said “If you say another word, I am going to beat you up.” That type of physical intimidation is a pretty typical experience for any boy who doesn’t have the build of a football player. You learn to sit somewhere else. Not to say that we intellectual types can’t also be cruel. I remember joking that the hockey team wasn’t just on average the dumbest people at Princeton, they were in fact the twelve dumbest. That’s not nice, and not completely true. (Although I do believe, as Malcolm Gladwell has written, that Ivy league schools tend to make sure to populate each class with a good contingent of less academic and more athletic students, so that they don’t end up with a class where the bottom 20% are suicidal former valedictorians. It’s nice for the psychology of the class to have people who can excel at other things besides academics, and not feel bad if their grades aren’t as good.) But of course I never said that to anyone’s face.

Ok, back to Kavanaugh. I hope people won’t take this the wrong way, but I consider myself to have come from a very privileged background, and at least to me, Kavanaugh doesn’t appear to be overly “privileged.” It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that he was economically in the lower half of the students at Georgetown Prep and Yale. To me, with his defensive “but I went to Yale” outbursts, he seems more like a sort of Gatsby type, a striver who is trying to fit in, a football player a bit too smart for his teammates, a prep school frat boy, not quite of the same class as his colleagues. He doesn’t have the same cock-sure demeanor that comes with the type of over-privileged prep school kids who know that no matter how badly they fail, they will always succeed. This might explain his need to pretend he remembers everything he did in high school, even when he was drunk, and to lie about other smaller things like his yearbook page at the hearing. He’s trying very hard to fit into a different crowd now.

It happened and Kavanaugh does remember. The second scenario is a worst case for Kavanaugh, but it seems highly unlikely to me that Kavanaugh would remember this episode. I met a friend recently and was surprised when at first he said he didn’t remember the time he almost swallowed a beer cap playing the eponymous drinking game, and had to be taken to the hospital. I had left the party early and did not witness it myself, but all of my friends were involved, and I am reminded of it every time I see him. When I mentioned it recently, he at first had no recollection at all. Obviously it was not something he had wanted to remember and so he had not revisited the episode as often as I did. By the time I brought it up to him, he had pretty much forgotten it. If someone can forget going to the hospital with a beer cap stuck in his throat, it seems unlikely that an aborted inebriated sexual assault would be remembered at all after thirty-six years. There has obviously been a lot of water under the bridge for Kavanaugh since that time, and without any reason to remember the incident, the memory would have disappeared.

It didn’t happen and Kavanaugh doesn’t remember. The third scenario is the one I might be more inclined to believe if Kavanaugh had behaved differently. Unlike Senator Flake, I don’t think that Kavanaugh’s belligerent demeanor during the hearing was at all consistent with what I would expect of an innocent person wrongly accused who recognizes that he cannot possibly remember anything that might disprove the allegation. Such a person might even feel sorry for the accuser, as Judge Kavanaugh’s daughter, believing he was innocent, obviously thought when she asked to pray for Blasey-Ford. An honest person would say that he understandably remembers no such event, nor much of anything about the high school hangout parties he attended, and would be a bit bewildered by the accusation. He wouldn’t be defensive, which is how Kavanaugh behaved most of the time, especially in his exchange with Senator Klobuchar. (“You’re asking about blackout. I don’t know, have you?”)

It didn’t happen and Kavanaugh does remember. The fourth scenario is implausible. Does anyone really believe that Kavanaugh has a photographic memory and can remember every single interaction in his youth so he can be 100% certain that the attack did not happen (because he remembers it not happening)? And yet this was Kavanaugh’s defense at the hearing. He is 100% certain he did not attack Blasey-Ford at a party thirty-six years ago. Why? Because he thinks he would remember it? A brief, drunken, fumbling, aborted attempt to wrestle a girl onto a bed and remove her clothes? After thirty-six years?

I was obviously more of a goody-two-shoes that Kavanaugh (I didn’t have my first sip of alcohol until the middle of my senior year, after I had been admitted early to Princeton), and I have been trying to remember all of the times that I had too much to drink. (By the way, it was remarkable to me that Kavanaugh simply could not answer a simple question about what he considered to be too many beers. “I don’t know. You know, we — whatever the chart says, a blood-alcohol chart.” Really? What non-alcoholic adult cannot answer that question? Moderate drinkers learn to know their limits when it comes to alcohol.) Anyway, I can remember five times I drank too much and threw up: Marlborough prom 1984; party in my dorm room sophomore year 1985-6; party at Terrace Club with the subway singer 1986; end of the bar exam July 1991; and KMZ 20th anniversary party in Chicago 1994. I have vivid memories of certain parts of all of these episodes. For example, at the Marlborough prom, where I very willingly let my date get me drunk, I remember asking a junior to drive my Buick station wagon because I was drunk and I tried to test him on calculus to make sure he was sober. I even remember asking him to pull the car over when it was time for me to throw up. At the Terrace Club party, I ended up in the infirmary because, brilliantly, I got hungry after consuming a bottle of red wine and decided to chase it down with a bowl of fruit loops and milk. The folks at the infirmary were convinced I was an alcoholic and made me go through all sorts of questionnaires in the morning about my drinking habits. The Chicago night was great; dressed in a tuxedo, we went from a formal party at the Natural History Museum to a rave-type club called the CroBar. That was fun, but the room was spinning the next morning and I had to really work hard to make my flight back to LA. Maybe I didn’t throw up that time. In any case, I still have a pretty good memory of these things, perhaps because I didn’t actually drink too much very often, and haven’t done that in over twenty years.

One of my concerns with Brett Kavanaugh is that I get the feeling from his testimony that he is still a heavy drinker. I can imagine that even during his several background checks no one bothered to volunteer that he occasionally drinks too much. After all, would you want to be the one to step up and try to torpedo a friend or colleague who sometimes has one too many? It would not surprise me at all if now, after these allegations have come out, we find more people stepping forward to speak about Kavanaugh’s drinking, and not just while he was in school. Drinking problems are notorious among lawyers, and Kavanaugh has been known to make light of these issues, even while speaking to law students. To me, Kavanaugh appears likely to be a high-functioning alcoholic (see “get angry when confronted about drinking.”) Current drinking allegations might even make President Trump more likely to withdraw the nomination, as the tee-totaling president is very sensitive on the subject. (His older brother died of alcoholism at age 43.)

But all that may be just my own wishful thinking. You see, the wish is really the father of the idea. And that is important for one further reason. Trump and his Republican allies bash the FBI all the time for what they feel is an unfair, biased approach taken in the Russia investigation. But as with anything else, there is really only one type of investigating and that is the wishful type. The evidence doesn’t just fall in your lap; you have to find it. And you won’t find it unless you actively go out and look for it. You look for things you want to find. You have to want to find it, or nothing happens. So of course the investigators getting a FISA warrant on Carter Page thought that they would find evidence of wrongdoing. That’s why they sought the warrant. And it sure looks like they had probable cause to do so. The same goes for the new investigation of Judge Kavanaugh. The FBI won’t find anything unless they really want to find something. Which witnesses to interview, which leads to follow, it all comes down to the desire of the prosecutor. Does he want to do a perfunctory investigation, just enough to say he did something? Or does he want to really find something incriminating or exculpatory. That will determine how far he goes. If I were investigating this case, the first stop after Blasey-Ford would be Kavanaugh himself. But have you heard any reports of a real Kavanaugh interview? The Senate questioning of him was superficial at best. Take the July 1 party at his friend Timmy’s house. What does he remember about that party? Who was there? What did they do? How much did they drink? Did anything memorable happen? Chances are he remembers very little, but maybe there are still some details worth pursing. And what about all of those whopping lies about the meaning of his yearbook page (Renate Alumnius, Boof, Devil’s Triangle, etc)? Will he repeat those to the FBI? In any case, if you don’t hear that the FBI talked to Kavanaugh, you’ll know that this wasn’t an investigation where they were trying to find anything. Because the wish is the father of the idea.