The former NY Times music critic Donal Henahan died this week. And so it is time for me to publish the satire I wrote after a particularly egregious anti-Schoenberg article he penned in January 1991 (And So We Bid Farewell To Atonality), shortly before his retirement. I’ll reprint Henahan’s original article below my satire. At the bottom you can read a letter I wrote to Henahan on July 4, 1990. He must have thought of his January 6, 1991 article as some sort of (lame) reply. He won’t be missed, at least not by me.

January 19, 1991

Classical View/Randol Schoenberg

And So We Bid Farewell To A Donality

If we look back over 20th Century Music Criticism, which some of us are now in a position to do, one fact stands out: criticism of severely atonal compositions, once regarded as the bulwark of the past, is leaving remarkably few ripples. The seemingly inevitable criticism of the break with tonal music, with its hierarchy of clichés, its modulations and gravitations from ignorance to stupidity, was not a long time coming, though it can be dated conveniently, however incorrectly, from Schoenberg’s invention of the 12-tone system in the early 20’s.

Criticism of atonality, however, was not simply one further step backwards in an evolutionary process. In effect, atonality threw critics into convulsive fits of reactionary fervor, as if they had been thrown into their own bathtubs and had their heads held under, causing severe brain damage and filling their ears with water so they could no longer hear any music at all. A few survived to work for large newspapers, teaching the old orthodoxy, presumably those for whom brain damage and deafness were no impediment. Many others, as they sank from view, could at least find solace in the belief that by criticizing the abandonment of tonality they were taking part in a necessary antihistorical backlash.

Firm believers in that faith are no longer easy to find, even on the newspapers where criticism of atonality in its most rigorous form — post-Downes Conservatism — was once the only esthetically correct position. Criticism of serialism is, of course, the god that failed, but even freer and less dogmatic forms of criticism have shown little ability to please demanding readers. Incontinent Lambast predicted this development accurately 56 years ago in his eccentric but perceptive little book, “Music Hoya-to-ho! A Study of Music Criticism in Decline.” Lambast’s name became a byword for lambasting in less-advanced circles, but his main thesis bears up quite well in comparison with the stacks of more pretentious drivel that paint the 20th Century as the beginning of the end for all musical creativity. Time and truth have proved to be on Lambast’s side. One may find today an occasional reactionary critic willing to concede what the concertgoing public grasped decades ago: that while the abandonment of tonality was a perfectly logical step, criticism of it was ridiculously constricted in expressive potential.

Or, if you allow a word misunderstood by all critics of atonalism, in meaning. No matter how you define meaning in music criticism, there is astonishingly little of it to be found in the great mass of criticism emanating from papers like the New York Times — except, note, where words or scenarios are used by the composer to give the music critics something nonmusical to write about which they might understand, as in Henahan’s favorable critiques of Schoenberg’s “Moses und Aron” or Berg’s “Lulu.” Purely instrumental works in systematically atonal idioms, like Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto, can leave the average unmusical critic of modern music untouched and shamefully eager for intermission. The work’s technical ingenuity is of course completely incomprehensible to the unschooled critics, who wouldn’t know an audible subtlety of expression or dramatic power if it hit them in the face, no doubt because the dialectic energies inherent in the intelligent criticism of music are presumably unavailable to the typical critic of atonal music. Most critics, of course, could discern beauties of logic or design, if only by reading the score, but, alas, critics of atonal music don’t know how. Far from being able to approach the study of music, their ability to comprehend abstraction is usually limited to extracting square roots without a computer or reading subway timetables.

Critics of atonal music, it must now be apparent to all, have been unable to develop a system of musical rhetoric that would transcend the mundane pleasures to be had from the mere shuffling and arranging of derogatory words. Some highly critical articles on pre-Serial music, like Stravinsky’s ”Sacre du Printemps,” can give an impression of at least heartfelt distress in the face of incomprehension.

“The music of Le Sacre du Printemps baffles verbal description. To say that much of it is hideous as sound is a mild description. There is certainly an impelling rhythm traceable. Practically it has no relation to music at all as most of us understand the word.” (Musical Times, London, August 1, 1913)

Critics of some other landmark works in that interim genre, like Schoenberg’s own Five Pieces for Orchestra (Op. 16), evoked vague feelings of anxiety, dread or anger.

“If there is anything more utterly monstrous, more hideous and more artistically squalid than Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, it can only be some other composition by their creator or by one of his disciples.” (Felix Borowski, Chicago Record Herald, November 1, 1913)

The narrow range of their responses is generally excused as a reflection of the critics’ own stupidity, their pervasive unmusicality and anti-intellectualism. But audiences composed of people who live in this same century have not bought their irrational bunk. We have seen music criticism, they say in effect, and this is not it.

These readers, agree with them or not, have a point. The critics’ frugality of expression compares poorly with the depths of meaning that Schoenberg, Berg or Webern could call up with the simplest of their skills. Only Schubert can penetrate the dull-witted critics’ heart. They cling to the moorings provided by innumerable tonal conventions, but without them they are completely lost.

It may be no accident that while criticism of serious instrumental music has been in retreat during our century, criticism of opera has flourished. Opera differs fundamentally from instrumental music in that fat people in costumes explain everything. The critic doesn’t have to pretend he understands music to write a story about it. It is this crutch, as the musicologist Carrying Abottle has pointed out, that allowed the critics of Wagner to dispense with descriptions and analysis of music, which, as we’ve said before, they couldn’t understand.

“They began with the overture to the Flying Dutchman… I do not know whether I possess a sixth sense which seems necessary to understand and appreciate this new music, but I confess that violent fist blows on my head would not have caused a more disagreeable sensation.” (P.-A. Fiorentino, Constitutionnel, Paris, January 30, 1860)

Perhaps as much as Wagner’s harmonic innovation, it was his remarkable extension of key relationships which left the critics so befuddled. The composer of “Tristan und Isolde,” according to Ms. Abottle, “didn’t have to live long to see the music critics misread his work with their special blend of egotism and obtuseness.”

Schoenberg, as earlier works like “Gurrelieder” make plain, was the perfect post-Wagnerite. Perhaps it is the critics’ misreading of Schoenberg’s and Wagner’s music that we have to thank for the meaninglessness of so much 20th-century music criticism.

January 6, 1991

CLASSICAL VIEW

CLASSICAL VIEW; And So We Bid Farewell To Atonality

By Donal Henahan

If we look back over 20th-century music, which we are now in a position to do, one fact stands out: severely atonal composition, once regarded as the wave of the future, is leaving remarkably few ripples. The seemingly irrevocable break with tonal music, with its hierarchy of pitches, its modulations and gravitations from key to key, was a long time coming, though it can be dated conveniently from Schoenberg’s invention of the 12-tone system in the early 20’s. The codification of atonality, however, was not simply one more step in an evolutionary process. In effect, it threw composers into unknown waters and held their heads under. A few survived to build academic careers, teaching the new orthodoxy. Many others, as they sank from view, could at least find solace in the belief that by abandoning tonality they were taking part in a necessary historical development.

Firm believers in that faith are no longer easy to find, even on the campuses where atonality in its most rigorous form — post-Webern Serialism — was once the only esthetically correct position. Serialism is, of course, the god that failed, but even freer and less dogmatic forms of atonality have shown little ability to please demanding audiences. Constant Lambert predicted this development accurately 56 years ago in his eccentric but perceptive little book, “Music Ho! A Study of Music in Decline.” Lambert’s name became a byword for philistinism in advanced circles, but his main thesis bears up quite well in comparison with the stacks of more pretentious volumes that paint the 20th century as a golden age of musical creativity. Time and truth have proved to be on Lambert’s side. One may find today an occasional avant-garde critic willing to concede what the concertgoing public grasped decades ago: that while the abandonment of tonality may have been a perfectly logical step, what took its place was ridiculously constricted in expressive potential.

Or, if you allow an easily misunderstood word, in meaning. No matter how you define meaning in music, there is astonishingly little of it to be found in the great mass of atonal works — except, note, where words or scenarios are used for support, as in Schoenberg’s “Moses und Aron” or Berg’s “Lulu.” Purely instrumental works in systematically atonal idioms, like Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto, can leave a reasonably experienced listener to modern music untouched and shamefully eager for intermission. Their technical ingenuity does not seem to be matched by audible subtleties of expression or dramatic power, no doubt because the dialectic energies inherent in traditional key-centered systems are not available to the atonal composer. In many severely atonal works, of course, one may discern beauties of logic or design, if only by reading the score. But abstract satisfactions are also available in other activities, like extracting square roots without a computer or reading subway timetables.

Atonal theorists, it must now be apparent to all, have been unable to develop a system of musical rhetoric that would transcend the mundane pleasures to be had from the mere shuffling and arranging of pitches. Some highly dissonant pre-Serial music, like Stravinsky’s “Sacre du Printemps” or Bartok’s “Miraculous Mandarin,” can give an impression of movement and meaning through sheer motor rhythm. Some landmark works in that interim genre, like Schoenberg’s own Five Pieces for Orchestra (Op. 16), may evoke vague feelings — anxiety, dread or anger. The narrow range is generally excused as a reflection of this century’s Weltschmerz, its pervasive mood of alienation and sadness. But audiences composed of people who live in this same century have not bought this rationale. We have heard music, they say in effect, and this is not it.

These listeners, agree with them or not, have a point. Atonality’s frugality of expression compares poorly with the depths of meaning that Bach could call upon with the simplest of tonal devices, like the shift from minor to major in the Chaconne. Schubert is able to penetrate the heart merely by shifting from E flat to D flat in the first movement of his posthumous Sonata in B flat or by inserting those startling silences in his “Unfinished” Symphony. The moorings provided by innumerable tonal conventions were implicitly understood and relied upon by audiences until quite recently: without them, no composer could hope to suggest the harmonic uncertainties and eventual exaltations that Beethoven achieves with a few trilled measures in the coda of Opus 109.

It may be no accident that while serious instrumental music has been in retreat during our century, opera has flourished. Opera differs fundamentally from instrumental music in that words and action in opera explain everything. The composer may convey what he means independent of purely musical — or better to say, tonal — devices. It was this freedom, as the musicologist Carolyn Abbate has pointed out, that allowed Wagner to dispense with the traditional practices of modulation, with their built-in gravitation toward drama and emotional expression. Perhaps as much as his harmonic heresies, it was Wagner’s libertarian approach to key relationships that later composers found most useful in undermining the old tonal regime. The composer of “Tristan und Isolde,” according to Ms. Abbate, “lived long enough to observe the new generation of symphonists, and with a mixture of egotism and astuteness saw them as imitators ‘misreading’ his work.”

Schoenberg, as earlier works like “Gurrelieder” make plain, was the perfect post-Wagnerite. Perhaps it is his misreading of Wagner’s freedoms that we have to thank for the meaninglessness of so much 20th-century music.

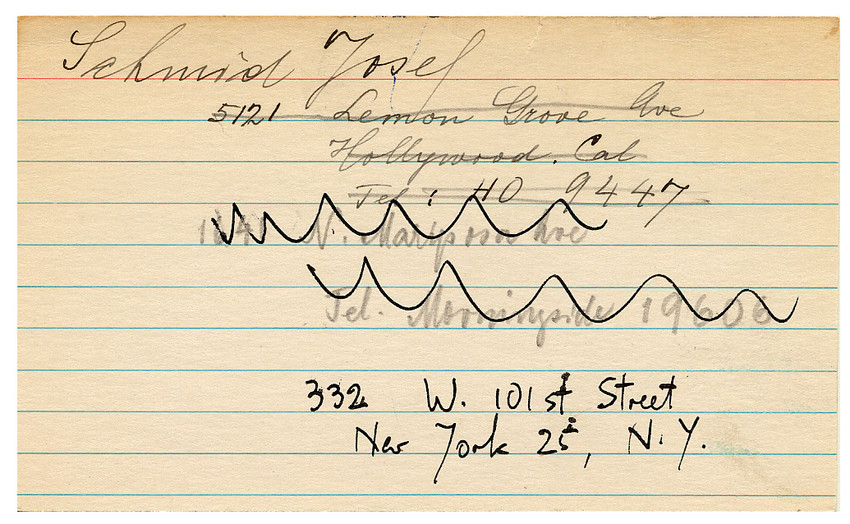

July 4, 1990

To the Music Editor of the New York Times:

Dear Mr. Henahan,

After seeing my grandfather, Arnold Schoenberg, maligned in the pages of your newspaper for the last six years, I have at last decided to initiate a correspondence by which I hope to correct some misinformation you and your staff have been propagating.

In his article on David Diamond, K. Robert Schwarz claims that “the artistic climate of the 1950’s reflected an obsession with the notion of the avant-garde, which searched for the new — whether in serialism, electronics or indeterminacy — and scorned the past.”

You and your writers make a habit, when singing the praises of neo-conservative music, of arguing that there once was a time when “serial” music was so dominant that it was performed to the exclusion of modern tonal composers’ efforts. Mostly this serialist hegemony is supposed to have occurred in the fifties.

While it may be true that after my grandfather’s death in 1951, interest in his music, and especially in the music of his pupil Anton Webern, increased in academic circles and among the best young composers in Europe and America, that interest sadly never made it over to the concert halls. The reasons for this have more to do with conservative critics and reactionary conductors than public disapproval.

Schwarz says that the performances of new tonal music began to “dry up” because the “fickle arbiters of musical taste now deemed atonality and serialism to be the wave of the future.” This argument has appeared many times in your paper. Do you believe it is true? Who were these “fickle arbiters”? Certainly no university in America had more than a handful of professors committed to “atonal” music. And then again, what power did these most devoted followers of Schoenberg’s music have? Did Roger Sessions and Milton Babbitt dictate the performances of the New York Philharmonic?

In any event, since I am young (23) and had no way of experiencing this period for myself, I would like some more information on this mythical period, where one could not only frequently hear serial music, but only hear serial music. I have the following questions:

1) During which years were there more performances of serial music than other modern music in New York City? Of all the classical music performed in New York City, what percentage was new or “modern” — either tonal or atonal?

2) During which years and for which composers were there more performances in New York City of the music of Arnold Schoenberg than there were of a) Copland, b) Bernstein, c) Barber, d) Thomson, e) Harris, f) Hanson, g) Diamond, h) Piston, i) Schuman, or any other tonal composer of significance?

3) Same question as #2, except don’t count Verklärte Nacht. Then count only 12-tone pieces.

4) Who were the “serial” composers who were performed most often, and which of their 12-tone works received the most performances? How were these composers and their works reviewed by the New York Times?

My questions all boil down to this: Can you offer any evidence to support your oft-repeated claims of serialist dominance in the post-war period? I am ready to be proven wrong, but I very much doubt that there ever was such a period.

Your paper’s position has been that Schoenberg’s music (serial, atonal, 12-tone, modern, ultra-modern, avant-garde, intellectual, brainy, thorny, difficult — whichever adjective you use to describe it) has been heard by the public and rejected. Again Schwarz writes, “[i]f the battle [for serial music] is lost, it is partly because audiences consistently rejected most of the music that emerged from the postwar avant-garde. ‘The big overall concertgoing public was always turned off,’ says Mr. Diamond. ‘That’s why even the greatest 12-tone works have never attracted an audience.’”

Until this fall, New York audiences will have not had a chance to “reject” Moses und Aron (at least in staged form). Which pieces then have turned off the public? Or is it perhaps the music critics of the New York Times who have done the rejecting, so that the audiences don’t have to? Isn’t it odd that in other countries Schoenberg’s music has been publicly acclaimed? In England last year, Schoenberg’s entire output was performed at the London Festival with much success. Why not in New York? When the Juilliard School tried to do a few Schoenberg works earlier this year, the New York Times mockingly reviewed it as an aberration.

If you take the time to research the questions I have asked you, you might find that Schoenberg’s music, and the music of his school, has never been given as much of a chance to be heard as the music of the many other anti-Schoenberg composers who have come and gone in this century. It seems quite possible to me that such “forgotten” tonal works as Diamond’s 3rd Symphony may have had more performances in New York City in the last 45 years than Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto.

It is one thing to advocate the music you feel is worthwhile. It is another thing altogether when in order to promote that music you rely on deprecating remarks against the music of Arnold Schoenberg. Yet this is not a new phenomenon, and it is not limited to Schoenberg. Since the end of World War II it has been the jingoistic nationalism of many American-born composers, supported by critics and conductors, which has pushed the music of their better trained, and in many ways more deserving, European-American colleagues off the concert stage. So, for example, we have heard much more of the native-born Americans listed above than their emigré counterparts — Korngold, Toch, Mihlaud, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Tansman, Zemlinsky and Weill, to name just the tonal ones. (I should also include on this list my maternal grandfather, Eric Zeisl, whose oblivion since his death in 1959 has been just as deep and just as undeserved as Mr. Diamond’s.) I doubt whether even the older and more established neo-classical composers — Stravinsky, Bartok, or Hindemith — have ever been performed in New York City more than Copland, Bernstein or Barber since 1945. And I have already questioned you about the Schoenberg school.

I hope you take these comments seriously (not serially?). I think it would make a worthwhile assignment for one of your staff writers to go through your paper’s concert reviews from the past to find out what was actually played during the post-war period and how it was received. I, for one, would be very glad to see the results published in your column.

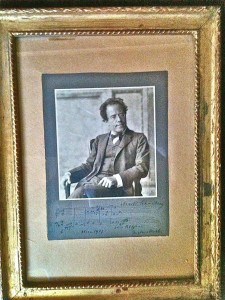

My grandfather respected your paper and understood its persuasive power. In 1948 he wrote to one of your predecessors, Olin Downes, in defense of Gustav Mahler. I hope that I have shown the same courage and perception in my letter to you.

Most sincerely,

Randol Schoenberg