Princeton University decided to actually recruit minority students in the mid-sixties. Since then the number of minority students has grown tremendously. For example, the class of ’65 had one black student, the class of ’90 will have 85-90, according to recent statistics from the Admissions Office.

Nine years ago, President William Bowen wrote an article for the Educational Record entitled, “Admissions and the Relevance of Race,” which was cited in the Supreme Court’s Bakke decision. His philosophy, in a nutshell, is that the inclusion of students from different backgrounds diversifies the community in a beneficial way, and that our goal should be a community “in which every individual, from every background, felt ‘unselfconsciously included.’ ” Bowen’s words still define the principles guiding the recruitment and admission for minority students.

The effort to achieve diversity, even within the minority group, prompted the Admissions Office to set up target numbers. These differ from quotas in that yearly fluctuations in the applicant pool could affect the number admitted. “The goal of the Admissions Office is to increase the quantity and quality of the minority applicant pool so that the number of students admitted will provide a “critical mass,” or a number of students within the minority groups enough to insure diversity within the group. Cummings explains, “What we try to do is create a decently sized community here. If a student is isolated, the potential to interact outside the group is inhibited. Exposure to diversity in one’s own group gives one the confidence to move beyond the group.”

Although Bowen admits in his article that numbers are important, the focus has been on a range, rather than a specific quantity. Provost Neil Rudenstein says that the University realizes that “there is a threshold below which students would be so isolated they wouldn’t want to come.” However, Dean of the College Joan Girgus cautions that raw numbers are not the goal. “We’ve really never thought about [diversity] in terms of numbers,” she says, “and I think it’s a mistake to think about it in terms of numbers.”

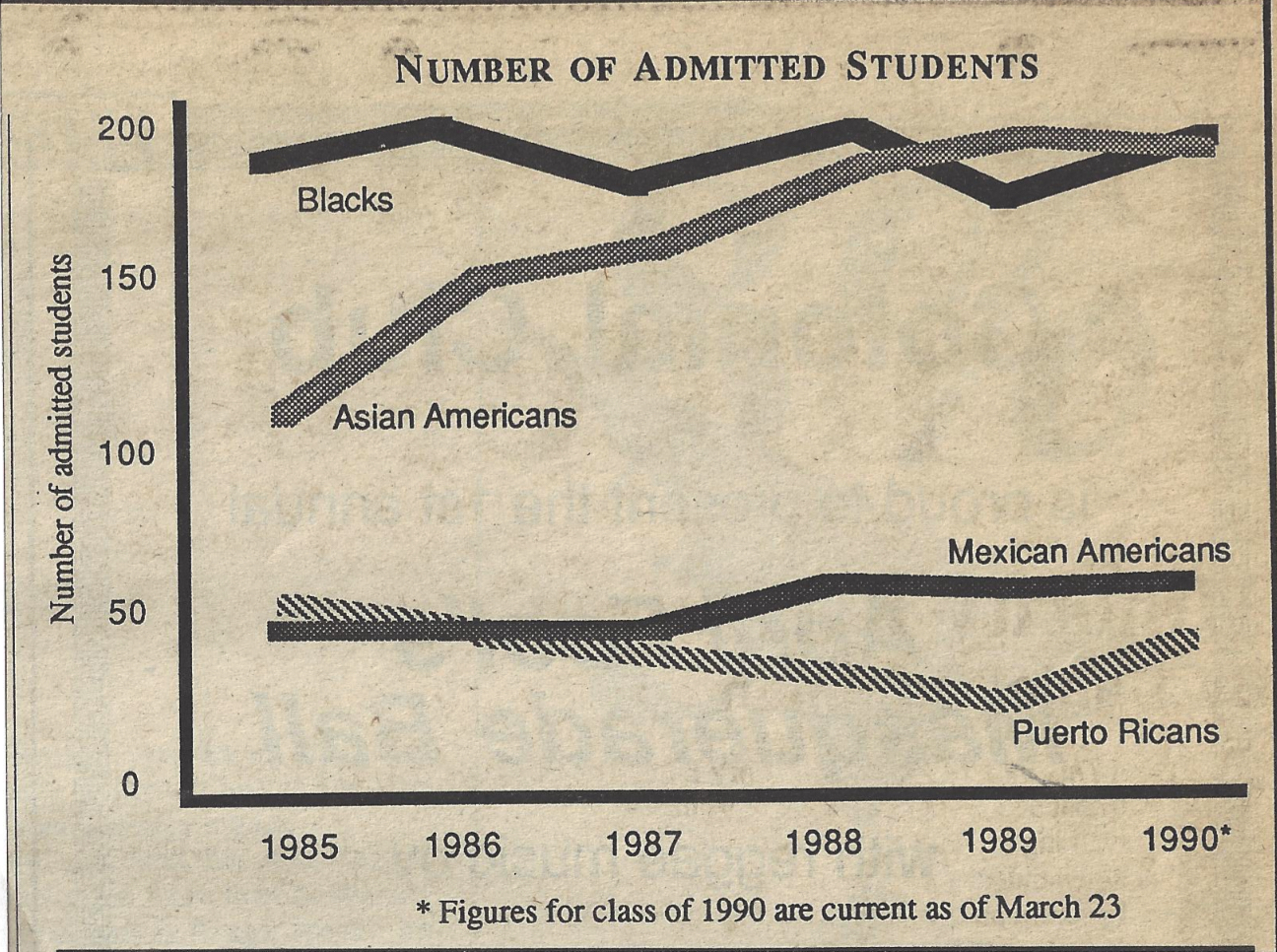

With Native Americans, the numbers applying have been so small (around 12-15 per year for the last 6 years) that achieving a critical mass is impossible. Other groups (blacks, Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, other Hispanics, and Asian Americans) have been more successful. With the exception of the Asian Americans, the number of applicants, admits and matriculants for each group has been steady over the last six years.

Still, yearly fluctuations can greatly affect the number in each group. Dean Cummings was not satisfied with the numbers for the class of ’89. Seventy is the number of black students in the freshman class,” he says, “and in my view that’s too low.” But the numbers have risen this year to more respectable figures. “We have over 100 more black applicants this year than last year. It’s one of the strongest black applicant pools we’ve seen.”

The increase this year is at least in part due to the new organization of minority recruiting which Cummings has implemented. Until he took over the job of Dean of Admissions, minority recruitment was relegated to specific minority admissions offices. Cummings recalls, “There was a separate office of minority recruiting charged pretty much the exclusive responsibility for minority students. For a number of reasons, that didn’t seem appropriate to me.” Cummings feels that all staff members are responsible for recruitment of minorities and all are responsible for the evaluation of minority students. His plan took a few years to implement, and he says that only this year was it completely effective.

Former Dean of Admissions James Wickenden, who left his post in 1983, says, “It was my goal to work towards a system where everybody’s responsibility would be the recruitment of certain kinds of students…. But while I was there, the minority applicant pool was not large enough to justify the switch.”

Cummings therefore inherited a system which separated minority recruiters from the people who evaluated students in their region. “In my view, you can’t separate recruitment and evaluation,” he says. “If you are going to evaluate students properly, you have to have recruited them in their own settings. You have to have a sense of what kind of educational opportunities they’ve had or not had. And you can’t gain an appreciation for those conditions unless you visit the schools, talk to counselors and teachers and so on. On the other hand, you can’t recruit unless you’re also involved in the evaluation of students. You don’t know what makes for a competitive candidate unless you’ve been reviewing folders and so on.”

Beginning with the class of ’88, recruitment and evaluation were done by the same people. Cumming also directed every staff member to be involved in minority recruiting. “I was also concerned that the staff members not directly involved with the recruitment of minority students, no matter how hard they try, wouldn’t feel themselves responsible for the whole range of concerns dealing with minority students if they themselves weren’t recruiting them,” he says.

Finally, Cummings worried about the image Princeton was sending out to minority students by having only minority staff members as minority recruiters. “I was concerned that we were sending a message to minority students that their status at the University was dependent solely upon the fact that they were minorities.” Involving all of the Admissions Office with minority recruiting, Cummings believes, “sends out a more positive image about the kind of a University Princeton is and the kind of belief we have in the importance of interaction among students with different backgrounds.”

While recruiting methods have changed, admissions criteria have stayed relatively stable. Blacks, Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and Puerto Ricans are given special consideration, just as alumni children and athletes are. However, the emphasis is placed not on the race of a student, but rather how well she/he has fared in relation to the opportunities available. “We measure all students, regardless of their ethnicity, or racial group, against the opportunities they have had or not had,” says Cummings.

By excluding Asian Americans from special consideration, the Admissions Office places more emphasis on attaining a critical mass than on compensating for racial prejudice. The Asian American applicant pool is large enough to naturally create a diverse applicant pool; therefore, they are given no special consideration. Conversely, Hispanics, who are not Mexican American or Puerto Rican, are also afforded little or no advantages in the admission process because their group has not been singled out by the administration for special consideration. Cummings sees this as a deficiency: “I think the people who make policy around here would do well to consider whether other Hispanics ought to be included as well, and given the same consideration as Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans.”

As for the immediate future, Cumming has just finished a 12-15 minute videotape which will be distributed to schools in the West and Southwest. He hopes that it will aid recruiting in cities in California and Texas, where a large amount of minority students reside. Each year, Princeton accepts more and more minority students, as Cummings says, “I think that most people will say a more diverse student body is a healthy student body.”

Published in Nassau Weekly (3/27/86)