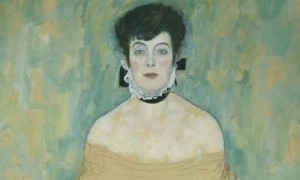

It might be news to some that London’s National Gallery is featuring an unreturned Nazi-looted painting from Austria in its current show “Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900.” Gustav Klimt’s beautiful unfinished portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, herself a Nazi victim, was owned by Amalie’s friend, the widower and Jewish sugar baron Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. In March 1938 Ferdinand was forced to flee Austria, and survived the war in Zurich, Switzerland. He died in November 1945. As he explained in his 1942 will, his “entire property in Vienna [had been] confiscated and sold off.” His heirs never found or recovered the portrait of Amalie.

The portrait of Amalie hung in Ferdinand’s bedroom since at least 1932, and was still in his home over nine months after Ferdinand fled, as it is listed first in an inventory created in January 1939 by the Nazi authorities tasked with distributing Ferdinand’s artworks and selling off his estate to pay off a discriminatory tax judgment that had been imposed. The lawyer Dr. Erich Führer, a high-ranking SS officer, had initially been hired by Ferdinand to protect his property, but in the end became the liquidator. Dr. Führer even kept twelve of Ferdinand’s paintings, including a Klimt, for himself. A 1943 report of the Central Monument Agency confirmed that “the Bloch-Bauer collection was completely liquidated by the Finance Office.” Dr. Führer was captured after the war and sentenced to hard labor.

The portrait of Amalie hung in Ferdinand’s bedroom since at least 1932, and was still in his home over nine months after Ferdinand fled, as it is listed first in an inventory created in January 1939 by the Nazi authorities tasked with distributing Ferdinand’s artworks and selling off his estate to pay off a discriminatory tax judgment that had been imposed. The lawyer Dr. Erich Führer, a high-ranking SS officer, had initially been hired by Ferdinand to protect his property, but in the end became the liquidator. Dr. Führer even kept twelve of Ferdinand’s paintings, including a Klimt, for himself. A 1943 report of the Central Monument Agency confirmed that “the Bloch-Bauer collection was completely liquidated by the Finance Office.” Dr. Führer was captured after the war and sentenced to hard labor.

No one knows exactly what Dr. Führer did with the portrait of Amalie, but Amalie’s non-Jewish son-in-law Wilhelm Müller-Hofmann supposedly came into possession of the painting during the War and sold it to the art dealer Vita Künstler. Vita held onto the painting for many years, finally donating it to the Austrian Gallery when she died in 2001 at the age of 101.

In 2006, several months after an Austrian arbitration panel decided to return five other Klimt paintings to Ferdinand’s heirs, the same panel had a change of heart and refused to return the portrait of Amalie. No doubt they were disappointed by the Austrian government’s decision not to exercise its option to purchase and keep the famous gold portrait of Ferdinand’s wife Adele in the country. Feeling great pressure, the arbitrators could not again give another painting to Ferdinand’s heirs, so the Panel denied the claim.

The evidence to support the denial was non-existent. In fact, the denial itself was premised on the novel theory that Ferdinand’s heirs should be required to demonstrate exactly what happened to the painting after Ferdinand fled the Nazi advance. The matter was complicated by the fact that Amalie’s family claimed the painting should be returned to them. The young Austrian historian Ruth Pleyer testified that, at age 97, Amalie’s daughter Hermine supposedly told her that she thought Ferdinand had arranged for the painting to be given to her family. Protokoll, p. 15. (Hermine failed to confirm this when the Director of the Austrian Galerie Gerbert Frodl and I each spoke to her.) Of course, Hermine had survived the war in hiding in Bavaria and could not possibly have had any first-hand knowledge anyway. In fact, in one private family letter of the time, she had complained of Ferdinand’s “unheard of behavior” in cutting off assistance to her mother, assuming incorrectly that he was living a life of wealth in exile (a common misimpression created by Nazi propaganda).

All of the parties to the arbitration, Ferdinand and Amalie’s heirs as well as the Republic of Austria, conceded that they did not know exactly what had happened to the painting or how it had left Ferdinand’s estate. This should have been the end of the matter. Under long-standing laws governing restitution, the victim is never required to demonstrate anything more than that the property had once been owned and was lost. But the Panel changed the law. They said that Austria’s new 1998 art restitution law only applied when it was absolutely proven that the artwork was expropriated, and not transferred in some other manner.

Ignoring the mountain of circumstantial evidence (i.e. Ferdinand was in Zurich, the painting was in Vienna, and his entire estate was liquidated), the Panel instead leaped to the conclusion that there was no confiscation, but rather that “at the instigation of Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, the painting was voluntarily given over to Hermine Müller-Hofmann without compensation.” Decision, p. 12-13. Again, there was absolutely no evidence to support this conclusion, nor apparently was there any thought given to explaining how exactly this could have been accomplished after Ferdinand’s estate was ordered liquidated. Ferdinand had himself written to the artist Oskar Kokoschka in 1941 “In Vienna and Bohemia they have taken everything away from me. Not even a souvenir has been left to me! Maybe I will get the two Klimt portraits of my poor wife and my portrait [by Kokoschka]. I should find that out this week. Otherwise I am totally impoverished.” As a work of a degenerate artist, the Kokoschka portrait was in fact delivered to Ferdinand, but, as we know, even the two portraits of his wife Adele were traded and sold by Dr. Führer to the Austrian Gallery. If Ferdinand could not even rescue for himself the portrait of his own wife, what would make anyone think that he could voluntarily make a gift of a painting to Amalie Zuckerkandl? As Prof. Hans Dolinar of Linz concluded, “the naive evaluation of the evidence by the arbitration panel is completely absurd.”

At the arbitration, I was not even concerned with the crazy theory, propounded by the Müller-Hofmann family, that Ferdinand had somehow arranged a gift to them from his exile. Why not? Because such a gift could only have been undertaken as a result of Nazi persecution. As Prof. Georg Graf of Salzburg confirmed in his harshly critical review of the Panel’s decision, Austrian restitution law has always been interpreted to mandate the return of gifts made by victims who were forced to flee.

But the Panel refused to apply this law or any of the ordinary rules regarding restitution of property that had been developed in the post-war period. They said that the 1998 art restitution law did not incorporate those older laws and therefore they no longer applied. On appeal, we argued very strongly, as did legal author Nikolaus Pitkowitz, that the decision of the Panel violated Austrian public policy. The best the court could say in upholding the decision was that the construction of the law by the Panel was “not unthinkable” (nicht denkunmöglich). Appeal, p. 39. The Austrian Supreme Court affirmed, argued that it was possible that the Austrian parliament intended to reverse 50 years of restitution laws when it formulated its 1998 art restitution law, finding that such a construction was not against Austrian public policy.

The great tragic irony is that shortly after these terrible decisions, the Austrian art restitution advisory board, which had forced the arbitration by refusing to return the portrait of Amalie, clarified its position on the 1998 law and suddenly decided that it should return artworks that would be considered returnable under the old restitution laws. Had they followed this rule with the portrait of Amalie, it would also have been returned.

So, the portrait of Amalie is a Nazi-looted painting, wrongly withheld by the arbitration Panel. Under Austrian law, as it is currently being interpreted, the painting would be returned to Ferdinand’s heirs. The only thing that is necessary is for the Minister of Culture and the art restitution advisory board to reconsider the case. I have been waiting seven years for this reconsideration to take place. Perhaps before the National Gallery returns the painting to the Austrian Gallery in Vienna, it should request a new determination by the Austrian art restitution advisory board. That way this misappropriated painting can finally be returned.

(All documents relating to the Amalie Zuckerkandl painting can be found at http://www.bslaw.com/altmann/Zuckerkandl/.)

Dear Randall Schoenberg,

I loved the movie Woman in Gold, including the musical score. I especially liked the Mozart aria that Fritz Altmann sang in the wedding reception scene. Can you tell me what is the name of this aria and from what Opera is it? My daughter, who spent a semester studying in Vienna, is getting married in July and we would like to have this song sung at the wedding.

Thank you,

Tom Cramer

Dear Randol Schoenberg,

Please excuse my mispelling of your name. You must be very proud of what you did for the cause of justice and the retrieval of stolen art!

Tom Cramer

Tom, I think it is Mozart Don Giovanni, Deh vieni alla finestra (Don Giovanni serenading a chambermaid). See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcab-DwNMDo

Dear Mr. Schoenberg,

I can’t thank you enough for your reply. This was my first foray into the world of blogs and posting and I must say, I am thoroughly spoiled. Having you, one of the key, real-life figures in the story, respond has made my day, my week, my month!

By the way, the week before we saw the movie, my wife and I were in New York City and went to the Neue Gallery. Your communique is the icing on the cake of a great memory!

Tom