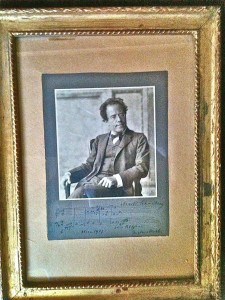

A missing photograph of Gustav Mahler with a dedication to Arnold Schoenberg has recently been found in the San Fernando Valley. The photo was given to Schoenberg probably before Mahler’s departure to New York in 1907. You can see it hanging on the wall above Schoenberg’s desk (to the left, below Schoenberg’s portrait of Mahler) in this photo from around 1912.  My aunt Nuria remembers seeing the photo when she was growing up, so it must have also hung in the Schoenberg study at least through the mid-1950s (when Nuria moved to Venice, Italy). When my grandmother Gertrud died in early 1967, after a brief illness, the study was locked up and made available only to scholars. In the early 1970s, Sonja Lane began working on a catalogue which was then used by Charles Sachs as an inventory when the archives were donated to the University of Southern California. The photograph does not appear in that inventory, and there is no trace of it having been at USC. Nuria noticed that the photo with Mahler’s dedication, and the companion photo of Mahler, were missing between 1987 and 1991 when she was working at the archives at USC on her document biography, Lebensgeschichte in Begengungen. She found empty frames that she believed were the frames that had housed the photos, but could not locate the photos themselves.

My aunt Nuria remembers seeing the photo when she was growing up, so it must have also hung in the Schoenberg study at least through the mid-1950s (when Nuria moved to Venice, Italy). When my grandmother Gertrud died in early 1967, after a brief illness, the study was locked up and made available only to scholars. In the early 1970s, Sonja Lane began working on a catalogue which was then used by Charles Sachs as an inventory when the archives were donated to the University of Southern California. The photograph does not appear in that inventory, and there is no trace of it having been at USC. Nuria noticed that the photo with Mahler’s dedication, and the companion photo of Mahler, were missing between 1987 and 1991 when she was working at the archives at USC on her document biography, Lebensgeschichte in Begengungen. She found empty frames that she believed were the frames that had housed the photos, but could not locate the photos themselves.  She reported this to the archivist R. Wayne Shoaf. After the archives were moved in 1997 to the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna, Nuria again told the new archivist, Therese Muxeneder, that these photos were missing.

She reported this to the archivist R. Wayne Shoaf. After the archives were moved in 1997 to the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna, Nuria again told the new archivist, Therese Muxeneder, that these photos were missing.

In late July 2012, a man named Cliff Fraser Jr., using the e-mail address cfpronto@aol.com, e-mailed this image of the missing photograph to the Schönberg Center in Vienna saying “Hello, my name is Cliff and recently acquired a document concerning Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg. I was hoping that you could help me understand its significance.”

He later wrote “my grandfather [Abraham (Abe) Fraser] was a music teacher and took composition classes in the 1950’s from Joseph Schmidt [sic], a former student of Schoenberg. [M]y Grandfather died in 1987 and I just found the picture berried [sic] in back of the boiler room of his house (I could hardly see through the frame; I almost threw it away). I’m guessing that Schoenberg willed it to Schmidt who willed it to my grandfather. Amazing…”

Of course, Schoenberg did not mention this photo in his will, which gave his entire estate to his widow Gertrud Schoenberg. Josef Schmid (1890-1969) was a pupil of Alban Berg, not Schoenberg. In 1940, Schoenberg wrote to Robert Emmett Stuart “There live in America also two pupils of Alban Berg: Dr. Wiesengrund-Adorno and Mr. Josef Schmid. If you are interested I will find their addresses. . . . Mr. Josef Schmied [sic] has been conductor in Prague, Berlin, and other places. He is a very good pianist, has studied theory with Berg. Whether he composes or not, is unknown to me.”

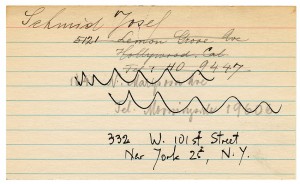

The Schönberg Center has an address card for Josef Schmid, with the notes: “Josef Schmid (born Germany, 1890 – died New York City, 1969) was a conductor, composer, and composition teacher. He was one of the first students of Alban Berg, with whom he studied before World War I.  As a conductor Schmid had been an assistant to both Zemlinsky and Erich Kleiber. As a composer Schmid was associated with Berg and Webern but considered himself a musical “godson” of Schoenberg. After the War Schmid emigrated to New York City and established himself as a teacher of composition, basing his teaching on the writings of Schoenbergs.”

As a conductor Schmid had been an assistant to both Zemlinsky and Erich Kleiber. As a composer Schmid was associated with Berg and Webern but considered himself a musical “godson” of Schoenberg. After the War Schmid emigrated to New York City and established himself as a teacher of composition, basing his teaching on the writings of Schoenbergs.”

First row left to right: Arnold, Ronald and Nuria Schoenberg, Mitzi Weiss, Werner Klemperer, Adolph Weiss. Second row: Unidentified woman, Gertrud Schoenberg, unidentified woman, Mr. & Mrs. Joseph Schmid, Mrs. Joseph Achron. Taken in front of the Brentwood home.

Based on the autobiography of Schmid’s pupil Joe Maneri, Cliff claimed that Schmid came to the United States in 1936 with the assistance of Schoenberg. There is a group photo taken in front of the Schoenberg home in Los Angeles around 1940 that shows Schmid and his wife visiting the Schoenbergs.

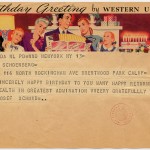

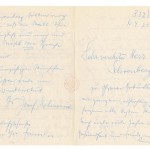

The Archive of the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna contains copies of a number of short letters and telegrams from Schmid to Schoenberg, such as this one from 1948 wishing happy birthday.  Schmid wrote two letters in September 1949 congratulating Schoenberg on his 75th birthday. In one of them, Schmid mentions the upcoming publication in book form of Schoenberg’s essays, recalling also Schoenberg’s lecture on Mahler in Vienna.

Schmid wrote two letters in September 1949 congratulating Schoenberg on his 75th birthday. In one of them, Schmid mentions the upcoming publication in book form of Schoenberg’s essays, recalling also Schoenberg’s lecture on Mahler in Vienna.

However, despite the fact that Schoenberg kept carbon copies of his letters, the correspondence archive does not contain any letters from Schoenberg to Schmid, indicating that it was a one-sided relationship of pupil (of a pupil) to master. A gift of the treasured Mahler photo from Schoenberg to Schmid seems highly unlikely.

However, despite the fact that Schoenberg kept carbon copies of his letters, the correspondence archive does not contain any letters from Schoenberg to Schmid, indicating that it was a one-sided relationship of pupil (of a pupil) to master. A gift of the treasured Mahler photo from Schoenberg to Schmid seems highly unlikely.

As this further evidence came to his attention, Cliff modified his theory to one even more unlikely, saying “It is far more likely that Schmid received the picture from Alban Berg.” However, there is no evidence of any gift of the photo from Schoenberg to Berg, despite the considerable documentation of their correspondence, including many letters referencing gifts. A gift to Berg, who died in 1935, is also inconsistent with Nuria’s recollection of the photograph at the Schoenberg home in Brentwood.

According to Cliff, his grandfather Abe Fraser “studied composition with Schmid in New York starting in 1951. In 1958 my Grandfather moved to LA and before his departure Schmid gave him the picture as a farewell gesture.” Based on information Cliff says he obtained from his grandmother, Abbey Fraser, who is apparently elderly and not well, Cliff stated that “this picture was a gift from my grandfather’s teacher.” However, Cliff’s father Dr. Cliff Fraser, Sr. says that his father Abe had a large autograph collection from people he had met, but he does not recall ever seeing the Mahler photograph.

At this stage, it is unclear what is true and what is simply a guess by Cliff in order to establish a provenance for the Mahler photograph. Cliff has behaved rather cagey throughout the whole process. Initially, he would not even provide his last name. He has refused to meet with us or speak to us on the phone. He will not let us see the photograph or the frame (which is obviously different from the original frame), nor will he send us any further pictures of them. At one point he referred us to his attorney “Paul” but did not provide a last name or any contact information and the attorney never contacted us. He wrote that his family wanted to sell the photo, then wrote that his grandmother had decided to keep the photo, and then, less than 24 hours later, wrote to us offering to sell it for $350,000. Cliff claimed to have a “notarized sworn declaration, under penalty of perjury” from his 94-year-old grandmother, supporting the claim that the photo was a gift to his grandfather, but then he refused to send us the declaration unless we agreed to purchase the photograph.

First page of the English version of Schoenberg’s essay on Mahler, which begins: “Instead of using my words, perhaps I should do best simply to say: I believe firmly and steadfastly that Gustav Mahler was one of the greatest men and artists”

In the view of the Schoenberg family, it appears likely that the photo was improperly taken at some point from the Schoenberg estate. It seems inconceivable that Schoenberg himself would ever have parted with such a treasured memento from his friend and benefactor Mahler. There is no evidence yet of any gift or sale of the photo by Arnold or Gertrud Schoenberg, who meticulously maintained the Schoenberg archives for decades. The very few items that were sold or given as gifts have all been well-documented. Given where the photo ended up, in Sherman Oaks, just a few miles away from the Schoenberg home in Brentwood, a more local trajectory seems likelier than the ones theorized by Cliff. Coincidentally, or not, there was an assistant university librarian at California State University, Los Angeles named Joseph Schmidt who worked on cataloguing the Schoenberg archives in 1973, before they were transferred to the Arnold Schoenberg Institute at USC. But it should be noted that no other items were noticed missing during the transfer of the archives from the Schoenberg home to USC. The photograph could very well have been taken prior to the transfer of the archives. [NB. The manuscript for the Op. 3 Songs had been microfilmed but is also now missing. Several drawings were taken from their frames and stolen during an exhibit at USC in the 1970s.]

Cliff has not disclosed what he intends to do next with the photograph. I will keep everyone posted on any further developments, and would welcome any information from the readers of this blog.

Great article on this story by Daniel Wakin the New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/11/arts/music/a-clue-to-whereabouts-of-schoenbergs-missing-mahler-photo.html?smid=fb-share

Clue Arises Regarding Lost Photo of Mahler

By DANIEL J. WAKIN

Published: October 10, 2012

Twenty-five years ago, when the daughter of Arnold Schoenberg was working through his archive for a book project, she came across an empty picture frame. It was missing what the Schoenberg family calls one of the composer’s most precious possessions: a signed picture of Gustav Mahler with a musical quotation from Mahler’s Symphony No. 2.

Now that picture appears to have re-emerged. A Los Angeles man has contacted the Schoenberg family and offered to sell it back for $350,000, saying the photograph was a gift to his grandfather from a composer in Schoenberg’s circle. Schoenberg family members say they doubt the gift story, suspect that the photo was at some point stolen by someone, and have demanded its return. They suggested that they might take legal action.

In the meantime, family members hope that publicizing the case will cause auction houses and dealers to become leery about making a deal for the photo. A grandson, E. Randol Schoenberg, outlined the matter in his blog, schoenblog.com.

Mr. Schoenberg said the man, Cliff Fraser, has refused to show the family the physical picture and has stopped communicating. Mr. Fraser did not respond to several e-mail and phone messages from a reporter this week.

While the mystery is perplexing, it is also a reminder of one of the more remarkable relationships in music history: between the older master, Mahler, who pushed the concept of the 19th-century symphony to its limits, and the young modernist, Schoenberg, whose conception of harmony changed the sound of classical music.

Word of the photograph’s existence first emerged in late July, when Mr. Fraser sent an e-mail to Therese Muxeneder, the archivist at the Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna.

“I was hoping that you could help me understand its significance,” he wrote, according to e-mails supplied by Mr. Schoenberg. Mr. Fraser said he had found the picture in the boiler room of his grandfather’s house. “I could hardly see through the frame,” he wrote. “I almost threw it away.”

Ms. Muxeneder responded that Mahler had probably given the photo to Schoenberg in 1907 as a farewell present just before he left Vienna to conduct the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

But Ms. Muxeneder was suspicious. Could the picture have been stolen?

Nuria Schoenberg Nono, the composer’s daughter, first noticed that the picture was missing in the late 1980s, when she was looking through the archive, at the University of Southern California at that time. She said she had told the archivist there of the missing picture. The archives moved to the Schoenberg Center, which opened in 1998, and Ms. Schoenberg Nono relayed the information to Ms. Muxeneder.

And so, two days after hearing from Mr. Fraser, Ms. Muxeneder alerted the Schoenberg family. Lawrence Schoenberg, one of Arnold Schoenberg’s two sons from his marriage to his second wife, Gertrud, contacted Mr. Fraser, and the two exchanged information in a series of e-mails in August and September.

Randol Schoenberg, whose father is Ronald Schoenberg, the other son by Gertrud, then took over negotiations. He asked Mr. Fraser to meet.

“This picture is my family’s property, without question,” Mr. Fraser wrote, and offered to sell it.

Randol Schoenberg balked, saying he wanted to establish provenance before discussing a sale.

Mr. Fraser threatened to sell it elsewhere. Mr. Schoenberg responded that no one would buy the picture “while there is a cloud of suspicion as to its provenance.”

After more fruitless negotiation, Mr. Schoenberg wrote that the photograph had been “taken improperly” and should be returned. “We will continue to pursue this matter with the seriousness it deserves,” he added.

In a telephone interview from Venice, where she lives, Ms. Schoenberg Nono ticked off possible paths. A gift to someone from Schoenberg? Impossible. “Mahler was the most important person in his life, his musical life,” she said. “Why would he ever give this away? This was something that bound him to the past.”

Schoenberg died in 1951, 17 years after having immigrated to the United States, and his study at home in Brentwood, Calif., remained intact. Could his wife, Gertrud, have given the photograph away? “My mother didn’t ever do anything that my father wouldn’t have done,” Ms. Schoenberg Nono said.

The study stayed locked after Gertrud’s death in 1967. An inventory made for the University of Southern California in the early 1970s did not list the photograph. Perhaps a researcher borrowed it from Gertrud Schoenberg and never returned it. Maybe it was removed during cataloging.

History lends support to the argument that Schoenberg would never have given away a Mahler memento. Schoenberg, who began with a love-hate relationship toward the older composer, came to revere him. “I have always venerated you awfully,” he wrote to Mahler in 1910. He asked Mahler for a loan to pay his rent, and received a year’s worth.

In a gushing 1909 letter to Mahler, addressed as “My dear Herr Direktor,” he wrote regarding the Symphony No. 7: “I am now really wholly yours. This is a certainty.” Schoenberg responded to a slighting review of the Seventh from Olin Downes, a critic for The New York Times, with a blistering letter.

In turn, Mahler publicly defended Schoenberg’s music, even if he admitted he might not understand it completely. At the end of his life, ailing, he urged family members to support his friend, who championed the atonal style of composition that came to dominate new music during the middle decades of the last century.

Mr. Fraser did not respond to requests for an interview, but his father, Cliff A. Fraser, did. Speaking by telephone from his home in Sherman Oaks, Calif., the older Mr. Fraser, 65 and a psychiatrist, said he and his son talked but were “not that close at this point, not by my choice.” He gave little information about his son, saying only that he was 35 and interested in studying veterinary medicine. The two, he said, have not discussed the letter. “I’d rather not know,” he said. “I don’t need intrigue.”

He provided a clue about part of the photograph’s journey. Mr. Fraser said his father, Abraham, was a musician and had studied with Josef Schmid, a student of Alban Berg, who was close to Schoenberg. Schmid considered himself a follower of Schoenberg.

But more than that, Abraham Fraser collected musical memorabilia. Perhaps he had stumbled across the photograph for sale, Mr. Fraser said, adding that his father did store scores and other materials in that boiler room. Mr. Fraser said he did not remember having seen the photo. “I was just a kid and not all that interested,” he said.

Regardless of provenance, the elder Mr. Fraser said he knew what he would do with the picture. He would give it back “in a second.”

“We all have families,” he said. “I would want my family to have what it’s supposed to have.”

A version of this article appeared in print on October 11, 2012, on page C1 of the New York edition with the headline: Clue Arises Regarding Lost Photo Of Mahler.

Pingback: NEW Mahler autograph on sale – Burning Bushes Music